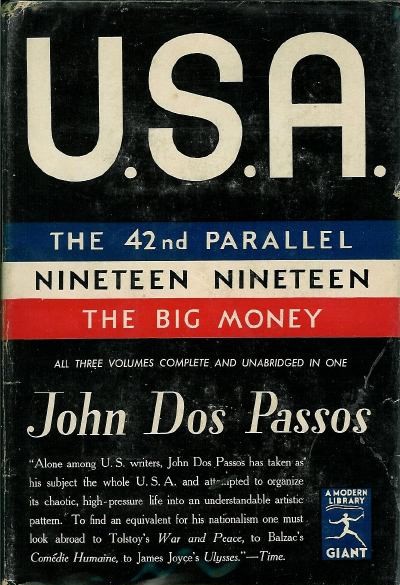

If you ever study Anglo-Modernism in grad school, you will occasionally be struck by how often the name of John Dos Passos will crop up without you ever being assigned anything to read by him. Here is a man whom Jean-Paul Sartre himself declared in 1936 to be “the greatest writer of our time”; his best-selling USA trilogy[1]The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), and The Big Money (1936). was compared by TIME magazine in the 1930s to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Balzac’s Human Comedy, and Joyce’s Ulysses; Gabriel García Márquez cited him as an influence upon Hundred Years of Solitude; and whom no less than Ernest Hemingway considered to be a close professional rival and trusted manuscript reader–yet Dos Passos is now all but forgotten, scarcely 50-odd years after his death. He appears on no syllabi, he gets selected for no book clubs, he is the subject of no major biographies.

So what happened? The rest of his generation is still doing fine, all things considered: Even when, say, Hemingway is mocked nowadays for his overly self-serious machismo, it is because Hemingway remains a widely-read, highly-recognizable name. Entire generations of American high school students can still quote the opening and closing lines to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. James Joyce is second only to Shakespeare for the sheer volume of literary scholarship produced about him. Your average Joe off the streets can still quote T.S. Eliot’s “This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang, but a whimper.” George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion (especially its musical adaptation My Fair Lady) still gets revived on the regular, as does Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. William Butler Yeats, William Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, H.D., D.H. Lawrence, Henry Miller, Ezra Pound–all of these names remain more or less recognizable, even if you personally have never cracked open a volume by them.

So what the heck happened to the reputation of John Dos Passos, who was once considered a peer to each of these giants? I skim his Wikipedia page, and am informed that many of his partisans believe his works became neglected once he pivoted more towards pro-McCarthy conservativism during the Cold War–but then, e.e. cummings was also pro-McCarthy, and he’s still read. For that matter, T.S. Eliot was quite openly conservative; his mentor Ezra Pound famously went full-bore, far-right fascist during WWII; Yeats, Shaw, Stein, and Lawrence all flirted with fascism at one point or another; and Marianne Moore voted for Nixon–yet they are all most definitively not neglected by scholars!

Or is it that so many of Dos Passos’s best-selling early works really were Left-Wing, pro-Labor agitprop of sorts, which resulted in his books becoming largely forgotten once that genre went out of style–especially after the hard-fought gains of the Labor movement (e.g. overtime pay, minimum wage, workman’s comp, legalized unions, collective bargaining, child labor laws, etc.) became normalized, even quotidian?[2]Happy Labor Day weekend, by the way. But then, George Orwell, John Steinbeck, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair were all unapologetically pro-Labor leftists, and their books are still circulating, to say the least.

I have lately been chugging through Dos Passos’ most acclaimed novels, Manhattan Transfer and the USA trilogy, and find that it is all written in a rather flat, impersonal, free indirect discourse that perhaps too many contemporary readers might find off-putting–but then, so is Gabriel García Márquez’s Hundred Years of Solitude, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, and Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives, and these are hardly neglected works. I wondered if maybe it’s his occasional use of fragmentary stream-of-conscious that fails to find new readers–but then, Joyce, Proust, and Faulkner keep getting read too[3]pretentiously, maybe, but they are still read.

I wondered if Dos Passos’ novels are perhaps too rooted in their early-20th century milieu to resonate with early-21st century readers–but then, so are the works of Fitzgerald, Steinbeck, Hemingway, Herman Hesse, and Remarque, and they remain almost comically popular. All the little vignettes and character-studies that make up Manhattan Transfer and USA are also rather plotless and directionless–but then, so is The Sun Also Rises, Tropic of Cancer, and Swann’s Way, and those still get read to death. I wondered too if his slice-of-life depictions of Americana are maybe too narrowly provincial to keep finding a wide audience–but then, so are the works of Joyce, Faulkner, Willa Cather, Robert Frost, Flannery O’Connor, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, D.H. Lawrence, etc. and etc., and I can still find all their books at Barnes & Noble.

Maybe the problem isn’t the style Dos Passos wrote in, but the fact that it appears to be nothing but style; his is not Hemingway’s iceberg wherein 7/8ths is below the surface, but it is all surface, with nothing to decipher. While numerous online sources inform me that he left the Left behind and became more critical of Socialism after WWII, it is not at all clear to me that he is as pro-Labor as reputed in his 1930s USA trilogy; for even acknowledging that he seems to have the most affection for his working-class characters, nevertheless he still holds them at the same ironic, arm’s-length remove as he holds his middle- and upper-class characters. That may be a useful technique for creating a cross-national panoply of vignettes and social conditions, but not so much for actually saying anything about any of it. Simply describing a Working Class man in prose isn’t the same as offering coherent commentary on him–or what exactly he wants the reader to do about it.

He is certainly not anti-Labor either, but perhaps that’s just it: neither hot nor cold, modern readers spew him from their mouths. Say what you will about all these other Modernist writers, but even the fascists all appear to have definite opinions about what the world should look like; even if you vehemently disagree with Pound or Hemingway or whomever, you at least know where they stand on their pet-issues–and more importantly, what their proposed solutions are. Dos Passos by contrast seems to evade taking a definite stand at every rhetorical turn, letting the reader draw their own conclusions. That may all be well and good and democratic, but avoid giving your reader an opinion long enough, and at a certain point, readers will get bored and quit asking for it entirely. The same aloofness that maybe made Dos Passos the coolest gent at the party 90 years ago is what finally made him the most boring one now.

It could also just be random chance: by way of comparison, The Great Gatsby was famously a commercial failure, a literary bomb, when it first debuted in 1925, and Fitzgerald died a broken man, until his works found second life after WWII. Woolf, Stein, and H.D. were all largely forgotten and neglected post-war, until they were rediscovered and championed by second-wave feminism in the 1970s. Heck, Shakespeare’s plays were considered crude and unfinished all throughout the 1700s–only fit to be performed once they’d been heavily re-written by “modern” masters like John Dryden–until the Romantics elevated him to the status of literary demi-God in the early-1800s. Maybe Dos Passos is simply passing through a similar period in the wilderness before he finally gets rediscovered again, who knows.[4]Although The New Yorker had an article just few years ago about “What John Dos Passos’s 1919 Got Right About 2019“–claiming that the Newsreel montages that open each chapter in … Continue reading

I was going to make a more explicit connection of Dos Passos to LDS studies (especially since there are some stray allusions to Salt Lake City throughout the USA trilogy–including the execution of Labor organizer Joe Hill[5]Most famous for the line, “Don’t mourn, organize!” in 1915 Utah), but this essay isn’t leaping and connecting like I’d hoped it would when I began. Maybe that is apropos for an essay on someone like John Dos Passos, whose fiction also leaps and jumps around without ever really landing someplace. To essay in French means literally “to try,” to attempt–and necessarily, not all attempts succeed. In fact, most of them fail. In fact, “all things must fail,” per Moroni 7:46. Including Dos Passos. Including every other writer I’ve mentioned here, for that matter.

If nothing else, I leave Dos Passos here as a reminder of how quickly we forget how quickly things can be forgotten; that by way of contrast, a demand for, say, archeological evidence of the Nephites is a little silly, since the vast majority of civilizations–like the vast majority of individuals–leave behind absolutely nothing, even when they intend to. We quote how the Holy Ghost brings all things to our remembrance–but then behold how quickly we can all forget the feeling of the Holy Ghost (“If ye have felt to sing the song of redeeming love, I would ask, can ye feel so now?” reads Alma 5:26–clearly implying that we often don’t), and that’s a purported member of the Eternal Godhead!

Maybe this is also all just a gentle reminder to not rely solely on irony to make your point, like Dos Passos did (irony may be necessary a-times, but it is primarily decontructive, not creative), but rather to actually stand for something, and to propose something sincere in its place. Even if others disagree with you, they will at least still remember you. Otherwise, lukewarm I spew and all that.

References[+]

| ↑1 | The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), and The Big Money (1936). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Happy Labor Day weekend, by the way. |

| ↑3 | pretentiously, maybe, but they are still read |

| ↑4 | Although The New Yorker had an article just few years ago about “What John Dos Passos’s 1919 Got Right About 2019“–claiming that the Newsreel montages that open each chapter in the USA trilogy anticipated modern social media feeds–but it’s been 4 years, so if that article was going to spark a resurgence in Dos Passos studies, it probably would’ve by now. |

| ↑5 | Most famous for the line, “Don’t mourn, organize!” |