Contemporary U.S. perceptions of Miguel de Cervantes’s 1605 novel Don Quixote are heavily filtered through the 1965 Broadway musical Man of La Mancha, whose big show-stopper “Dream the Impossible Dream” (featured most recently in the trailer for John Wick: Chapter 3) creates the impression that the novel’s thesis is that the world can be changed by those who dare to dream, or some such. Certainly when I was a missionary in the MTC 20-odd years ago, and Don Quixote was cited by a visiting General Authority during a large-group meeting–as a model for us missionaries to follow as we cheerfully proselyted in the face of nigh-constant rejection–it was specifically the Man of La Mancha version of the character that he was promoting. (Which would be entirely consistent within a Mormon milieu; it was the version of Don Quixote that EFY-mainstay Peter Breinholdt was also singing to in his local ’90s hit “I See Flowers“.)

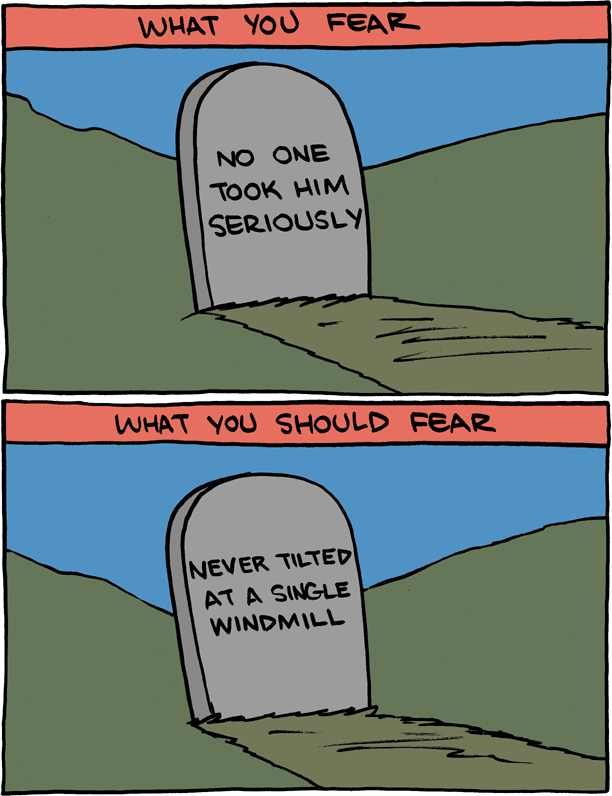

It wasn’t a necessarily poor analogy to make; for us teenage missionaries utterly unfamiliar with either the Broadway musical or the Spanish original, the rough archetype of Don Quixote was as good an example as any to follow. In not just Utah, but across the larger postmodern Anglosphere, Don Quixote is generally championed as an inspiring model to follow; the adjective “Quixotic” tends to signify a foolhardy-but-still-worthy cause; and the phrase “to tilt at windmills” is usually treated as an ultimately admirable and praiseworthy tendency. (Such was how the webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal deployed the term in one its more devastating cartoons):

I do not dispute the utility and attraction of the Man of La Mancha archetype, particularly when one is embarking on a possibly-doomed quest of one’s own. In fact, part of me suspects that the reason this particular interpretation of Don Quixote has gained such a foothold in the late-20th/early-21st century American psyche, is because the “quixotic” tendency lies at the heart of the entrepreneurial spirit that is at the foundation of the American mythology.

As we all know, 90% of all small businesses fail within their first year; most start-ups never get off the ground, most websites never take off, most sales never close, most apps never get downloaded, most bands never hit it big, most manuscripts never get published, most films never get made, most artists are never discovered, and so on and so forth; and we also all know that the vast majority of people who do strike it big do so through some dumb combination of inherited generational wealth, immensely serendipitous connections, and/or astronomically good luck being at the right place at the right time, and etc. Hence, to even begin to embark on any sort of entrepreneurial enterprise in the face of almost comically long-odds and the near-certainty of financial ruin if we do so, is to truly “tilt at windmills”–and it is in the best interests of late-capitalist elites to encourage and incentivize as many people as possible to be “quixotic,” so as to continue to the ceaseless churn of wealth-creation and sustained economic growth, wherein the only shame is in not constantly trying again. (A sort of literary equivalent to 50 Cents’ Get Rich or Die Trying). And if the vast majority of these aspiring mini-Quixotes end up getting smashed by the windmill blades, that is the price we are collectively willing to pay, apparently.

I am trying to be not to be cynical here; one can also argue that this Quixotic spirit is also vital for, say, any and every successful civil rights movement, or religious reformation, or artistic creation, or other much more worthy causes launched in the face of overwhelming adversity. I do not believe that that forgotten GA was out of line for quoting Man of La Mancha in an MTC devotional, nor do I believe that anyone else is wrong-headed to take this version of Don Quixote as a worthy model of emulation. For the record, I do indeed believe in the importance of radical positivity (or as Moroni was careful to emphasize, “A man must needs hope”). There are many Don Quixotes, and this one is as valid as any. But nor do I believe it an accident that this is the particular interpretation of Don Quixote that has come to predominate late-capitalist America, to the near-total exclusion of all others–the one most likely to encourage capitalistic entrepreneurship.

Because to anyone who has ever actually read the original Spanish novel, it scarcely needs repeating that this is not how Cervantes presents the character of Don Quixote at all.

If you ever take the opportunity to read the 1,000 page behemoth, you will find that the windmill episode only occupies the first half of chapter eight in Part One, and that Don Quixote is emphatically the butt of the joke. Cervantes very clearly means for you to laugh at him, not with him, and would be baffled by any calls to emulate his madness. Part One in particular is largely a sustained parody and satire of the knights-errant genre, not a celebration of the same. He is trying to kill off the genre, not revitalize it.

But Don Quixote isn’t considered a classic because of how it skewers a genre that was already musty even 400 years ago; no, Don Quixote is still read for how the novel itself repeatedly blurs the lines between fiction and reality in a manner that not only reflects the madness of its protagonist, but also anticipates meta-fiction and postmodernism by at least 300 years.

For early in the novel, when Don Quixote’s friends drag him back to La Mancha to try and cure him of his obvious and debilitating madness, they matter-of-factly follow the example of the contemporaneous Spanish Inquisition and start burning his books. Yet they don’t burn all of Don Quixote’s books: Cervantes consigns into the fire the works of his literary rivals, but saves those of his literary friends–and in his most comic touch, has the priest save an earlier novel authored by Cervantes himself, whom he says was a close friend of his who never got the credit he deserved. Although the meta-fiction here is still only a light touch, it is the first indication that Cervantes doesn’t just take knights-errant seriously, but doesn’t take any text seriously.

For in another chapter from Part One, Quixote gets into an argument with a fiery Basque horseman; in the heat of the moment, they both draw their swords and run at each other, and then…Cervantes informs the reader that he has run out of manuscript to translate! He had been translating an Arabic document recounting the exploits of this Don Quixote, he explains; and though Arabs are of course untrustworthy since they follow Mohamed instead of Christ, this must clearly be a true record, because otherwise why would a Muslim speak so glowingly of a Christian knight? The fact that this record has clearly been mocking Don Quixote–not to mention that the Arabic manuscript is itself an obvious fiction–creates multiple levels of meta-fictional sarcasm.

Yet Cervantes then reports that after he ran out of manuscript, he went to the market and bought some fish, only to find that the fish was wrapped in further Arabic script, which he promptly took to a local Moor to translate. Straightaway he learns the conclusion of the fight between Don Quixote and the Basque, and is pleased to report Quixote’s victory. This comic interruption takes an entire chapter resolve.

The meta-fiction doesn’t really kick into overdrive, however, until Part Two–published in 1615, ten years later, and that primarily to supercede a spurious sequel someone had written to try and cash in on Part One’s real-world popularity–when Don Quixote and his faithful peasant squire Sancho Panza, are informed by a college bachelor that the stories of their exploits have become popular all over Europe. Don Quixote and Sancho determine to embark on new adventures–and everywhere they travel, they are greeted and recognized by fans who start playing along, hailing him as a knight-errant so earnestly that he starts to actually be one. (In one rousing scene, someone even stands up and admonishes the cheering crowd for enabling such an obvious madman as he makes his triumphant entrance into a city, but he is swiftly shouted down as a killjoy–as Alma said to Korihor, why interrupt the people in their rejoicings?) We could multiple examples.

That is, the real world has influenced the novel’s production, just as the novel had in turn influenced the so-called “real world” (as though there is anything unreal about the physical text in your hands). Both the real world and the fictional world had been warped by and sucked into the narrative of Don Quixote’s own fictional world, in a manner that, again, blurs the boundaries between fiction and reality generally.

And it is here that I wish to come back full-circle to that MTC memory and address the Book of Mormon (which also has a missing-the-point Broadway musical).

To its critics, the Book of Mormon is a comically-obvious fraud, a clear fiction, created by a delusion farmboy at best or a conniving conman at worst. To its adherents, it is an inspired history, a revelation from God, the most correct book on the face of the Earth. Less often noted by either, however, is the fact that the Book of Mormon text itself is explicitly distrustful of the text. There are for example the repeated laments by the Book’s polyvocal speakers as to their own weakness and failures in writing (e.g. “Neither am I mighty in writing”, 2 Nephi 33:1; “for Lord thou hast made us mighty in word by faith, thou hast not made us mighty in writing”, Ether 12:23); there are the inevitable excisions made for condensing that highly-selective history onto a single-volume of metal plates (“there cannot be written in this book even an hundredth part” is a common stock phrase repeated throughout the text); the inclusion of a much earlier Jaredite history dating back to the Tower of Babel “when the languages were confounded,” heavily abridged by a prophet-exile named Ether after the Jaredites’ self-destruction, recovered and translated by the Nephites into their own now-dead language, then further abridged, annotated, and inserted into the Book of Mormon record by Moroni after the Nephites’ own self-destruction. There is Mormon 9:31 itself–“Condemn me not because of mine imperfection, neither my father, because of his imperfections”–and so forth. We could multiply examples; we all could.

Simply put, the Book of Mormon doesn’t want you to put all your trust in the text either! Like Cervantes, the Book of Mormon has no interest in promoting a bunch of textual literalists–that way quite literally lies madness. No, it is what the text represents, what it points towards, what it symbolizes, that is most important. Notably, Moroni 10:3-5–the master scripture we train all our missionaries to recite to potential converts above all others–does not promise that those who pray about these things will know whether the Book of Mormon itself is true, but whether these things are true.

And which things? Note the wording of verse 3: “Behold, I would exhort you that when ye shall read these things, if it be wisdom in God that ye should read them, that ye would remember how merciful the Lord hath been unto the children of men, from the creation of Adam even down until the time that ye shall receive these things, and ponder it in your hearts.” There is not a word in there about praying to know whether this was an accurate history (even if you believe the Nephites really existed, the Book of Mormon still isn’t a true history of them, simply because so much of necessity had to left out); no, Moroni couldn’t care less. He only cares whether you believe the mercy of God is true. All else is tangential.

As Nephi himself declares in his valedictory remarks, “If ye believe not in these words believe in Christ” (2 Nephi 33:10), and that is the proper attitude to take towards not only the Book of Mormon text, but all texts generally. The truth will never be found in the words, for all words are inherently unreliable in the first place. This is the message of Don Quixote, and one that is endorsed by the Book of Mormon. Always put your faith in what the words point towards, not the words themselves.

And that is a message I think should’ve been taught in the MTC, too.