Ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early ’90s, mainland China has been the LDS Church’s white whale. Surely, we reasoned, if our missionaries could finally penetrate the Iron Curtain–which to our amazement had fallen suddenly, in a moment, in an undreamt-of best-case scenario that didn’t even require a nuclear war to accomplish!–then truly the Lord was hastening the work in these Latter-days, and the gospel really would sound in every ear and from every climb! We naturally assumed that communist China, the most populous country on earth, would soon become the great and final field of labor ready to harvest. Church President Spencer W. Kimball had predicted as much, current-President Russel M. Nelson had studied Mandarin in preparation, and the rise of Temples in Hong Kong and Taiwan seemed to presage this imminent miracle.

Yet here we are 30+ years later, and mainland China remains as closed to LDS missionaries as ever. The brief, mild free speech thaw under Hu Jintao was promptly replaced by yet another freeze under Xi Jinping. Rather than import in Hong Kong’s democratic system after the handover, Beijing has instead violently imposed its own authoritarian regime upon the same. The Uyghur-Muslim concentration camps in Xinjiang have not only outraged the world, but clearly signaled that the present government is less interested than ever in tolerating “foreign” elements within their Han-Chinese ethno-state–which would naturally exclude us as well. And the communist party’s full-throated embrace of free-market principles never ushered in an accompanying era of free-thought and free-speech, but only proved (yet again) that despotism can co-exist with capitalism quite comfortably.[1]For that matter, the fact that the Church has grown so discouragingly slow in Russia–with the only former-Soviet-Bloc temple built so far being in Ukraine, which Russia is currently invading … Continue reading

Not that I’m saying mainland China will forever remain closed to LDS missionaries–or even to democracy and free speech, for that matter; pessimism is a tool of patriarchy and of power and of Satan himself–a form of coercing complicity with the injustices and horrors of this world–and must be opposed, which is incidentally why the Book of Mormon insists that “a man must needs hope” (Ether 12:6); hope is not only a feeling of uplift, but a strategy for resistance. Hence, I maintain that we can still have hope for both China and ourselves–politically, spiritually, in every which way–because (if you’ll indulge me in that hoariest of cliches) we have already been infiltrated by the one Western export with the greatest liberation potential of all: Rock ‘n Roll[2]Sometimes a cliche is a cliche because it’s true.. No, it is not capitalism, not religion, not Lockean political philosophy or Emersonian individualism or what have you that will save us, but the very musical genre that our oldest Youth Leaders warned us against the most[3]Obligatory reference to The Ramones’ “Chinese Rock.”.

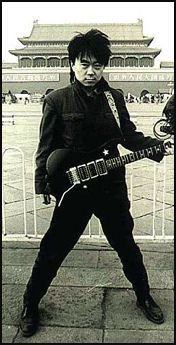

Enter Cui Jian.

Cui Jian (崔健: roughly pronounced “Tsway Jyen”) is widely considered to be “the Father of Chinese Rock”–Rock not just in the musical genre, but also in his innate sense of rebellion. The title of his seminal 1989 album 新长征路上的摇滚–Rock ‘n Roll on the New Long March–is a winking (not to mention ballsy) jab at the pretensions of China’s autocratic regime, which often drew upon Mao Zedong’s famed “Long March” against the Japanese Empire during WWII to legitimize its authority[4]There had in fact been a rhetorical push amongst Beijing leadership in the ’80s for a “New Long March” by which to recommit the populace to the Party.. Indeed, the LP’s lead single 一无所有, “Nothing To My Name,” was sung by no less than the Tienanmen Square student protestors later that very year.

Consequently, Cui Jian was banned for years from both Chinese radio and from performing in Beijing throughout the 1990s. But despite these attempts to silence him, Cui Jian continued to play sell-out crowds across the rest of mainland China. His enduring popularity was such that, when the concert ban was finally lifted, he was invited on stage by The Rolling Stones to sing “Wild Horses” when they finally visited Beijing in 2006.

Yet notwithstanding his popularity in humanity’s most populous nation, Rock ‘n Roll on the New Long March was for the longest time unavailable on iTunes, or even to torrent (believe me, I searched). I assumed the Chinese govt. must truly have a far and vindictive reach, to be able to so thoroughly suppress such a politically-provocative CD! Hence, when a single stray copy suddenly appeared on Amazon one day (this was before the advent of streaming), I quickly snatched it up, anxious to hear what actual Rock ‘n Roll rebellion sounds like, from a country where that actually means something.

So, you can imagine my disappointment upon discovering that Rock ‘n Roll on the New Long March sounds, quite frankly, like a Chinese Huey Lewis and the News. Serious, even that famed protest anthem “Nothing To My Name” sounds like a Phil Collins song. The album’s lack of stateside accessibility probably has less to do with govt. suppression than with the fact that we already have our own Huey Lewis and Phil Collins; we don’t need to import others. I supposed that in a dictatorship, any rockin’, no matter how mild, is still enough to be subversive.

However, I always give a new album a chance, and after a few spins, I did notice that Cui Jian isn’t simply imitating Western ’80s soft-rock; for example, “Nothing To My Name,” if you listen carefully, does feature some subtle and innovative integration of Chinese traditional instrumentation. Track 5 假行僧–“Fake Monk“–actually foregrounds these traditional sounds in interesting and engaging ways, creating new music rooted in the ancient.

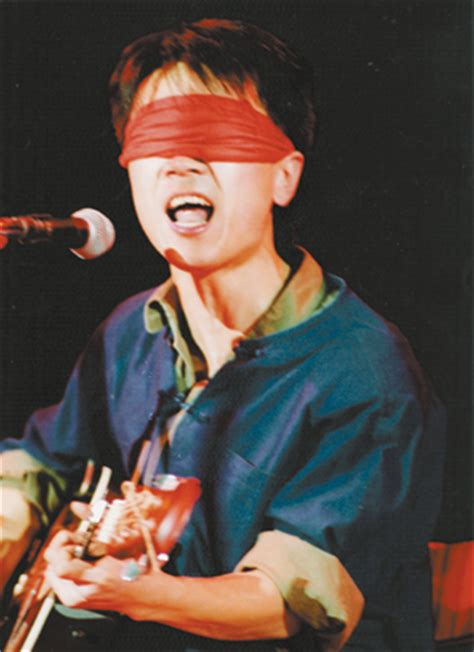

But I didn’t really connect with Cui Jian–I didn’t learn to love him for his own sake, and not just for his influence or what he represented–until I encountered his ’90s output, where he formally breaks with any hint of ‘80s soft-pop, and flies wild and free into the great unknown. Take for example the opening track off 红旗下的蛋–Balls Under the Red Flag–aptly entitled 飛了 “Flying“:

Now that’s something new! Here we see traditional Chinese sounds and instrumentation melded into Western-style rock, in a fusion that is utterly different from both and utterly spectacular. Official State suppression only made him bolder in his experimentation, not less, and there’s nothing more Rock ‘n Roll than that! (Especially when you compare him to all the gutless American bands who water down their sound for mere commercial considerations).

The depth of Cui Jian’s achievement can be gauged by comparing “Flying” to this 2005 cover[5]And the opening track to the tribute album Who Is Cui Jian?! of “Rock ‘n Roll on the New Long March” by Chinese band Reflector. Admittedly, I prefer this rip-roaring version of “New Long March” to the original…save that the original, whatever else may be its obvious ’80s soft-rock influences, still feels like something different. This 21st century cover may rock out more, but it also sounds exactly like a cover that, say, an American band would come up with. Two-odd decades later, a contemporary Chinese act, even one enthralled with Cui Jian, can still do no better than copy the Anglo bands.

But Cui Jian does not copy, he does not ape, he does not mimic, no: Cui Jian innovates, he creates, he is an artist. He takes Western music cues and turns them hard East, while taking Eastern tradition and turns them West. He is both rooted in China and transcends it; even the Rolling Stones once sang “I Know It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll“—cowardly, almost apologetically—but Cui Jian knows it’s so much more. He is what Rock ‘n Roll rebellion actually sounds like, what is should sound like, and what it sounds like when Rock ‘n Roll matters.

And I can’t help but wonder: If/When the Church finally enters mainland China, it will not be an Anglo-American Mormonism that will emerge, but a Chinese syncretism, one that will likewise be strange yet strangely-familiar, innovative, new–and that is as it should be. Is China not yet ready for the Church? Or are we, as a Church, not yet ready for China? That is, is it actually a parochial Utah-centrism that inhibits our growth–not just in China, but everywhere else as well? For that matter, is it a narrow Amero-centrism that inhibits our growth on an individual level? If we truly believe that we will be creating worlds–nay, universes–one day in the distant eternities, can we not have the courage and the temerity to create something unique and new now? It can be difficult to do so in against the broad indifference and commercial considerations of the Western world–but it is even more difficult in the face of the active governmental hostility of mainland China, and Cui Jian still had the courage to pull it off.

And I wonder what it would look like for us to display that same level of courage.

References[+]

| ↑1 | For that matter, the fact that the Church has grown so discouragingly slow in Russia–with the only former-Soviet-Bloc temple built so far being in Ukraine, which Russia is currently invading amidst revived nuclear brinkmanship–also indicates that our initial wave of optimism at the end of the Cold War was a touch premature. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Sometimes a cliche is a cliche because it’s true. |

| ↑3 | Obligatory reference to The Ramones’ “Chinese Rock.” |

| ↑4 | There had in fact been a rhetorical push amongst Beijing leadership in the ’80s for a “New Long March” by which to recommit the populace to the Party. |

| ↑5 | And the opening track to the tribute album Who Is Cui Jian?! |