The whole mid-2000s Indie-Rock era was admittedly an overwhelmingly white scene; the one serious exception to this trend was TV on the Radio, a multi-racial psychedelic-Rock band out of Brooklyn, NY. Anchored by the twin vocal threat of Tunde Adebimpe and Kyp Malone–as well as guitarist-producer David Sitek–the award-winning band was cited as a favorite by no less than David Bowie (who even condescended to sing back-up on their 2006 single “Province“), and were regularly cited by critics in the same breath as Arcade Fire, Modest Mouse, The Strokes, Sufjan Stevens, Regina Spektor, Andrew Bird, Animal Collective, Postal Service, The White Stripes, LCD Soundsystem, and other leading lights of the aughts. They were reflective of their era (e.g. “I Was a Lover,” the epic opener to Return to Cookie Mountain, perfectly captures the anxiety and exhaustion of the Bush-era War on Terror years), yet also prophetic: their 2008 single “Golden Age” seemed custom-built for the brief ray of optimism that preceded the Obama era, while their 2014 track “Troubles” seemed to anticipate the downfall that would shortly come to pass.

Yet curiously, there has not been a new TV on the Radio album since 2014. The rise of Trump that “Troubles” presaged–not to mention Black Lives Matter, #metoo, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, George Floyd, and the pandemic–all went un-noted and un-commented upon by a band that had had its fingers on the zeitgeist for a solid decade. They never officially broke-up, mind you; they in fact just went on tour last year to promote the 20th anniversary of their debut Desperate Youth, Blood Thirsty Babes. But they have made no noise about recording new material. They have quietly transitioned into legacy status, a relic of a bygone era, without fanfare or formal announcement.

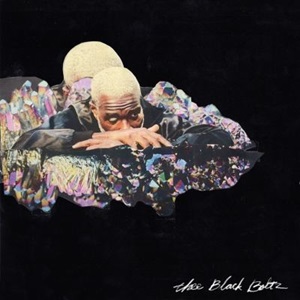

This is all the context within which Tunde Adebimpe dropped his first solo record Three Black Boltz in April of 2025. To be clear, Adebimpe happily joined TV on the Radio on their reunion tours last year, has had nothing but nice things to say about his old band, and recently expressed “hope” that the group would record again soon; but it is also equally clear, reading between the lines, that Adebimpe finally grew fed up with waiting on his band-mates, so went ahead and released something new by himself. He just turned 50 after all, his sister Jamoke died of a heart-attack during the pandemic, and so had (I suspect) become keenly aware in his advancing age that there is always less time than you think—so he ceased to procrastinate the day of his repentance (or at least of his recording contract).

The resulting album, unsurprisingly, sounds very much like a long-delayed TV on the Radio album. It certainly follows the Poppier, more R&B-influenced trajectory of their final trilogy of Dear Science, Nine Types of Light, and Seeds; one cannot help but imagine how Kyp Malone might’ve joined in with his trademark falsetto on at least a few of the tracks, or how David Sitek could’ve punched up the production a bit.

But his other TV on the Radio band-mates are not here, and though the sound is similar, Tunde Adebimpe has (perhaps wisely) not actually attempted to make a new TV on the Radio record. It lacks any of the grandiosity or ambition of those older albums. Even the shorter running time (a breezy 35 minutes–and far cry from the hour-long opuses of TV on the Radio’s first two LPs) seems to acknowledge the lack of a full band here. It comes off less like a long-gestating project than a recently thrown-together playlist. Likewise, the video for the lead single “Magnetic” simply features a very grey-haired (yet also distractingly fit) Adebimpe singing alone with a microphone and speaker in front of a fixed camera, accompanied only by a lone young woman dancing in the background.

As is fitting for a solo album, Adebimpe has turned inwards rather than outwards on Three Black Boltz; he avoids making the sort of grand political statements that TV on the Radio records always seemed to gesture towards. He makes no overt references to, say, a resurgent white-supremacism in this country, nor any open calls for resistance or revolt. The album’s lone ballad “ILY” (acronym for “I Love You”) is purportedly written in memory of his late sister, and the rest of the record follows suit in staying personal. Nevertheless, as this site has discussed before, the personal is political and the political is personal; and if Adebimpe has turned inwards here, that by no means signified he’s not aware of the world around him.

Indeed, he opens “Magnetic” by singing, “I was thinkin’ bout my time in space/I was thinkin’ bout the human race,” which indicates that it is precisely the fallen nature of humanity at large that he is brooding about the most. He identifies ours as “the age of tenderness and rage” and as “the end of days,” and both descriptors are accurate. Yet his is also an ancient complaint: lamentations about the viciousness and cruelty of humanity, how we refuse to learn wisdom, or to love one another, can be found in Isaiah, Jeremiah, Malachi, Enoch, Mormon, and Moroni. Per Moses 7:33, even God the Father himself up in the heavens (“thinkin’ ’bout my time in space”) is driven to open weeping, because He has “given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood.” The situation, needless to say, remains unchanged today.

Yet what is also intriguing to note, is that “Magnetic” is unmistakably a dance song. If this record is a party as funeral, it is still defiantly a party! These tracks are supposed to be fun! In spite of–or perhaps because of–the wicked state of the world, Adebimpe wants you to enjoy yourself!

Perhaps this is the meaning behind “Adam fell that men might be, and men are that they might have joy”–that joy comes about because this world is fallen! Perhaps such is why Alma 50:23 informs us that in the midst of an existential war for survival, that “there never was a happier time among the people of Nephi, since the days of Nephi, than in the days of Moroni.” One imagines that the Nephites were singing and dancing too, as they marched out to meet their brethren and enemies in mortal combat. In this sense, perhaps Tunde Adebimpe has written an album of revolt and resistance after all.