Almost too on the nose, I had to fly to a funeral over Easter weekend. Even more on the nose, I watched the 2024 film Conclave as my in-flight movie just three days before Pope Francis passed away Easter Monday.

I had written before about seeing Francis speak at St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican; I had been there in 2013 when he was still the new Pontiff and firmly in the honeymoon stage with the world’s Catholics. I was reading Dante’s Inferno at the time, where in Canto XIX, Dante the Pilgrim scolds Pop Nicholas III, who is cramped upside down in a burning hole for the sin of Simony–that is, the selling of indulgences (which even the most orthodox Catholics knew was a sin long before Martin Luther came along)–declaiming:

“Therefore stay here, for thou art justly punished, And keep safe guard o’er the ill-gotten money […]

And were it not that still forbids me,

The reverence for the keys superlative,

Thou hadst in keeping in the gladsome life,

I would make use of words more grievous still;

Because your avarice afflicts the world, Trampling the good and lifting the depraved.” (Henry Wordsworth Longfellow translation)

As I wrote previously: “Dante respects the office of Pope, even as he has nothing but well-earned contempt for this particular Pope himself. That is, even the medieval Italians knew their Church was often corrupt! (And they’re the ones with ‘Papal infallibility,’ not us.) Tell Catholics about their Church’s sins and they’ll just shrug their shoulders and say, ‘Yeah, we know.’ For them, the Church is true, even when its leaders aren’t.

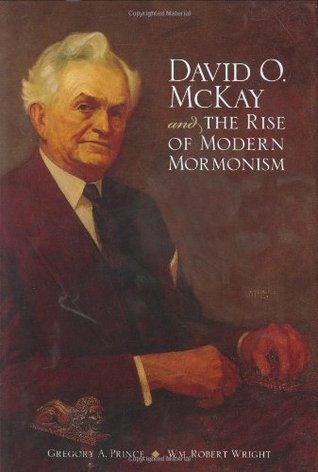

“Quite frankly, as the modern LDS Church comes to grapple with its own, shall we say, more ‘colorful’ history (e.g. polygamy, racist Priesthood bans, Mountain Meadows, Bushman’s Rough Stone Rolling, Prince and Wrights’ David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism, and just so many more), perhaps a healthy dose of Catholic ‘The-Church-is-true-even-when-the-people-aren’t’ is exactly what the doctor ordered. The Lord uses flawed men to do his work; what’s more, according to our own theology, the War in Heaven was fought over free agency, which means the Almighty allows us to make mistakes–and that to an incredibly radical degree–yes, even our senior-most leaders, because we have all sinned and fallen far short of the glory of God.”

This same Catholic sense of “The-Church-is-true-even-when-the-people-aren’t” likewise permeates Conclave. The film is a fictionalized dramatization of the conclave of the Cardinals that always convenes for the selection of a new Pope. Politicking, backroom dealings, intrigues, and petty in-fighting dominate the proceedings. An African Cardinal who had been a frontrunner for the Papacy sees his candidacy derailed when the Nigerian Nun he had once impregnated during a moment of weakness 30 years earlier shows up; but then the Canadian Cardinal who had secretly arranged for that Nun to show up during the Conclave is exposed for his perfidy, which derails his candidacy as well. The Dean who performs all these investigations is repeatedly accused of trying to maneuver himself to be selected Pope, despite the fact that he is privately suffering a crisis of faith (he had begged the last Pope to be released from his duties, but his resignation was refused). The liberals are trying desperately to block the election of a conservative Italian cardinal who wants to undo Vatican II and all the reforms of the past 60 years, but they have difficulty settling on a least-bad option. When one Cardinal says he feels like he’s at an American Political convention, one is tempted to scoff that maybe it’s the other way around.

Part of me of course wants to contrast all this infighting against the wisdom of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, where all of our successions are always clean, simple, and predictable: as has been the case since Brigham Young, whoever the senior-most Apostle is, becomes next Church President. But then (as noted above), I’ve read Prince and Wrights’ David O. McKay and The Rise of Modern Mormonism before.

This book is a rousing read, and deserves all of its high praise; but then, part of what makes it so engaging is just how ridden with back-room politicking it is, as well. Someone once told co-author Gregory Prince that if you swap out all the names, it could be the history of just any other history of corporate intrigue. The way the Canadian liberal Hugh B. Brown fought pretty much single-handedly to end the Black Priesthood ban, but was constantly blocked and out-maneuvered by the Twelve’s conservatives; the huge power clashes between Ernest P. Wilkenson and Harold B. Lee, who loathed each other, over the direction of BYU; the political headaches caused by Ezra Taft Benson’s John Birch membership, and literary headaches caused by Bruce R. McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine, and so on and so forth. There isn’t a small personality anywhere in the book.

It is all, again, a rousing story well-told! It also is kind of depressing, that our senior leadership is just as susceptible to internal politics and strifes and intrigues as literally every other human organization. In these moments, part of me actually respects that the Catholics are at least upfront about it, and don’t pretend to do differently.

But then, are the Mormons and the Catholics really so different after all? I don’t just mean in the sense that we have succession controversies and belief in Apostolic Priesthood Keys and tensions between conservative and (comparatively) liberal senior leadership or what have you, but in the faith and hope that despite all our shared human frailty, God is still guiding us.

In LDS discourse, we cite examples such as Spencer W. Kimball, old and frail and forgettable and near death, suddenly finding himself thrust into the hot-seat after Harold B. Lee died surprisingly young–only for Kimball to then be the one to finally end the Priesthood ban and radically change the Church for decades to come. Clearly God knew who he wanted in charge of His Church, we note with wonder. We might also note that Thomas E. Monson, a humanitarian who codified “helping the poor” as a mission of the Church, ascended to the Presidency at the dawn of the Great Recession; while Russell M. Nelson, a medical professional, became Church President just in time for the COVID-19 pandemic. The Church is true and more importantly God is true, even when men are not.

In the movie Conclave, this same sentiment is expressed when a Muslim suicide-bomber hits the roof of the Vatican while the Cardinals are in the middle of yet another round of voting. Nobody is killed, but they are obviously all shaken. In short order, they learn that a coordinated series of suicide bombers have been striking targets all across Europe. For that conservative Italian Cardinal, this is just the opportunity he needs to consolidate support for the Papacy, as he goes on a well-rehearsed rant about how all of the “religious tolerance” and “moral relativism” of the liberals has only led to this, that “we are at war!”, and what they need now is a “strong leader” to push back against the barbarity of “these animals” literally at our doors.

But then a quiet Mexican Cardinal–one who had been appointed by the last Pope in secret to oversee a dangerous humanitarian mission in Kabul, and had been lurking in the background unnoticed throughout the film–stands up and asks gently, “With respect, Brother, what do you know of war?” He describes his own missionary efforts in Congo, Baghdad, and Afghanistan, of seeing the bodies piled up on the side of the road, and of what it truly means to follow the example of Christ amidst all this violence. He with mildness notes the pettiness of all present, and admits he is unlikely to ever be invited back to a Conclave again, but cannot help but declare with all humility that “The Church is not tradition. The Church is whatever we do next.”

The next round of voting resumes, and the Cardinals sit down with their ballots, with cuts on their faces and debris on their gowns. As the Dean contemplates whose name to write down, he hears a bird singing. He gazes upwards at the hole in the ceiling left by the suicide-bomber, and sees the heavenly light of the sun shining down upon them.

This obscure Mexican Cardinal from Kabul–who wasn’t even being considered as a darkhorse candidate for the vast majority of the film–wins the majority necessary to be selected Pope. After reluctantly accepting, he takes upon himself the name of Innocent. The Lord had guided and positioned exactly who He needed to be the next Pontiff. (There is one last twist at the end when the Dean discovers that the new Pope was born Intersex–which the previous Pope had attempted to cover up by sending him to get a sex-change operation in Switzerland–but he declined it, because “I am as God made me”. In any case, it doesn’t thwart his ordination, because the Dean, exhausted by weeks of endless back-room intrigues, decides to just let this secret be.) Although the film had presented the titular Conclave in deeply cynical and pessimistic tones, it ultimately ends on a faith-affirming note.

Was this ending largely just Hollywood fantasy? Yes, of course; but it is also representative for how hundreds of millions of Catholics worldwide believe (or at least hope) the election of a new Pope functions, as well–that for all of the small-minded pettiness of the frail, imperfect men involved, that the guiding hand of God will still be manifest in all things. Such, I dare say, is also how the most believing members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints proceed. I hope the Catholic Church is similarly guided in their selection of the next Pope.