This one is for hardcore Lutz fans only.

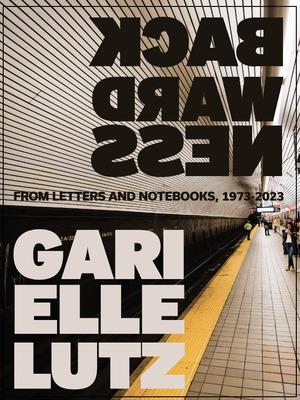

Indie-lit hero and short-story writer Garielle Lutz–who in 2022 was even cited as a possible darkhorse candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature–released The Complete Gary Lutz with Tyrant Books in 2019 (we once discussed on this very site how that tome’s introduction was written by none other than Mormonism’s own Brian Evenson). Lutz, however, has been steadily undermining that increasingly-inaccurate title ever since: first with the release of Worsted in 2021, under her new moniker of Garielle Lutz once she came out as trans at the ripe old age of 65; and now with the 2024 release of Backwardness: From Letters and Notebooks, 1973-2023, which is nearly a third longer than both The Complete Gary Lutz and Worsted combined.

As the subtitle indicates, the way this 932-page door-stopper manages to get so long is by collecting together excerpts from Lutz’s voluminous letters and notebooks dating all the way back to her college years in the ’70s, clear on down to almost the present moment. If you are already on Lutz’s wave-length, it is a pleasure to witness the slow yet steady development of Lutz’s craft through the years; though the opening pages are a little tedious and dull (if still hypnotically compelling), by about a third the way through, it becomes clear that Lutz had perfected her writing voice as early as the 1980s. Indeed, starting around page 300 or so, Backwardness starts to read like a regular Lutz collection, only exhileratingly longer. (Perhaps it can be treated as the long-novel that every short-story writer is expected to produce nowadays–the capstone Ulysses to their introductory Dubliners–as though only the fat novel counts). The great revelation here, then, is that Lutz had apparently perfected her idiosyncratic prose-style years before taking workshops from Gordon Lish and getting Stories In The Worst Way published with Alfred A. Knopf in 1995.

Speaking of which: Lutz curiously never once in these various notebooks and letters discusses meeting Gordon Lish (whom she has only had rave and gracious things to say about in interviews), nor is there one peep in there about the publication of that momentous first book, of the excitement and anxiety that most writers feel about such a milestone. In fact, if you somehow went into this book cold, you would have no clue whatsoever that Lutz is a critically-acclaimed author with a robust cult following. Instead, Lutz narrates her own life in the same aggressively ordinary, passive, and off-kilter manner that she narrates any of the characters in her stories. (It will perhaps come as zero surprise that Lutz has lived the same way she writes.) If you are an aspiring writer yourself, you will learn far about how much Lutz paid for a bag of M&Ms and a Nestle bar while a college sophomore at Kuntztown University in 1974 then you ever will about her writing development.

For that matter, here is a brief list of major world events that Lutz lived through but neglects to reflect upon in this sprawling collection: the Watergate scandal; the end of the Vietnam War; the Reagan years as a closeted queer person; the end of the Cold War; 9/11 (only mentioned in passing three or four times); the invasion of Iraq; the 2008 stock crash; and etc. Starting at pg. 706, there are finally some references to the COVID-19 pandemic, but only as a backdrop to some awkward grocery store interactions, and how it disrupted her constant dining out at Burger King.

Heck, Lutz doesn’t even go into all that much detail on, say, her failed marriage (which surely must’ve provided material for her 2011 collection Divorcer?). Her late-in-life autism diagnosis is only mentioned parenthetically on pages 735 and 782; and her first faculty appointment (nowadays a major life event for grad students in our disgracefully desiccated job market) is narrated self-deprecatingly only on pg. 736. Lutz once taught as a Visiting Professor at Syracuse University‘s prestigious Creative Writing Program (the same one her favorite musician Lou Reed graduated from), but of that life event, she only mentions how large the Dollar Tree was in Syracuse. There is almost nothing on her coming out as trans, which she neglects to detail not from any apparent fear of the political repercussions, but simply out of sheer disinterest. The only time Lutz actually goes into emotional depth on something intensely personal is on the decline and death of her parents–with whom she apparently had a complex and codependent relationship–which I think could have easily been excerpted into a harrowing chapbook or novella, but is instead buried deep around pages 670-700. Otherwise, all the usual things one expects to be listed as major life milestones are conspicuously left out. Backwardness could almost more accurately be subtitled, “50 years of junk food receipts, awkward conversations, and being disappointed by Lou Reed.”

But then, that very valoration of the quotidian and ordinary over the so-called “newsworthy” is exactly what makes Lutz so compelling. Terryl Givens once said that part of the religious genius of Joseph Smith was how he exalted the ordinary, and infused even the dirt and stones beneath our feet with intelligences and spirit. Literally nothing is below our notice in this religion, or at least shouldn’t be. Lutz, despite being utterly indifferent to religion herself, intuits the same; even the candy bar receipts are worthy of our attention, more than the kingdoms and vanities of the earth. If Backwardness is like Ulysses at all, it is in its similar hyper-attention to the every day, forgettable, quotidian details of our lives that most people ignore, in a manner that elevates the ordinary to the sublime. “The worth of souls is great,” reads one of our most cherished scriptures; which in turn indicates that even the supposedly most unremarkable of lives, the kinds that Lutz describes across all her fiction, is still of infinite worth–the manifestation of a God in embryo–and therefore worthy of our deepest reverence and attention.

Nevertheless, this is still the sort of tome that I can only recommend to the hardcore fan. For everyone else, start with Stories In The Worst Way before determining if you wish to explore further, and then work your way forwards from there. As for Backwardness, it is almost overwhelming to the point of burnout to read that many Lutzian sentences in one place; it’s like trying to take in all of the Lourvre, or the Met, or the British Museum, in one day–at a certain point, you mind shorts out and all these masterpieces simply start to blur together.