Back when I adjuncted at LDS Business College (now Ensign College) a decade or so ago, I would invariably, every semester, get several student papers arguing that one can “choose to be happy” in any situation one is in. They doubtless first heard the doctrine in some religion or marketing class, and perhaps thought it would please their instructors to parrot the idea right back at them; some of them may have even sincerely believed it, who knows.

Such papers were always by a young student (no student over the age of 22 said something so ridiculous), as well as white, middle-to-upper-class, and North American (none of my students from Latin-America, Africa, Asia, eastern Europe, or even the lower tax brackets of the U.S. ever wrote such a thing, either). It’s apparently easy for folks who’ve never had real problems to tell everyone else to get over theirs. (In fairness I suppose, according to Alma 7:12, even Christ himself had to suffer the infinite pains of the Atonement before he could fully “how to succor his people according to their infirmities.” If even God didn’t know how to relate to us till he suffered, then what of the rest of us?)

There are of course multiple problems with the rhetoric of “choosing to be happy,” viz: it makes the clinically depressed feel even worse; telling them to “just get over it” is like telling a cancer patient to “just get healthy”; it perpetuates the pernicious Puritan doctrine that only the sinful suffer, and therefore if you’re sad you must deserve it (so monstrously similar to saying that that girl was asking for it, I mean, just look at that dress…); it’s also weird for adherents of a religion that preaches “are we not all beggars?” to blame the beggar for their own sufferings, or for believers of “wickedness never was happiness” to claim that happiness is a choice–does that mean I can be evil and still choose to be happy about it, even in hell?

Then there’s just the gross misreadings that these students perform, like when they cite “the patience of Job,” the Biblical figure who supposedly bore all his sufferings with quiet patience, somehow skipping the 40 straight chapters of Job complaining very loudly to God. Serious, does no one actually read the Book of Job anymore? I swear, I need no other defense of literary studies than this: we learn how to read what a text actually says, not what everyone thinks it says. But Job’s not even the most egregious misreading these students perform.

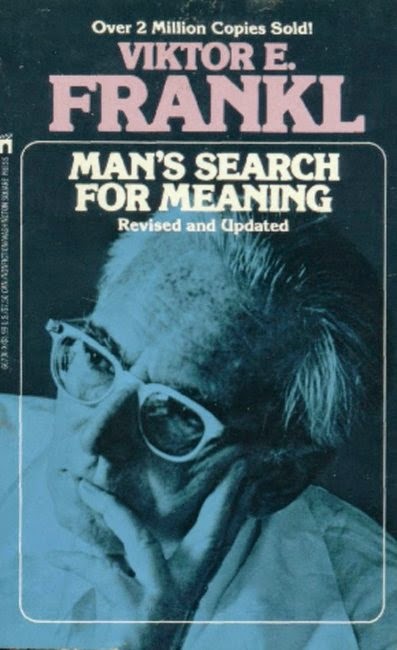

No, that dubious distinction belongs to Victor Frankl, the Jewish-Austrian psychologist who survived the Holocaust, then wrote a massively best-selling 1946 book about his experience in the Death Camps called Man’s Search for Meaning. The gist of the book is that man’s primary motivation is not pleasure (as Freud initially thought) or power (as Nietzsche taught), but meaning. If you can find a meaning, then you can handle most anything, Frankl argues, even Dachau; he repeatedly quotes Nietzsche: “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.” Hence, Frankl was able to survive the Death Camps when many physically stronger men succumbed, because he was able to find meaning in his immense sufferings.

These young students then somehow conflate this search for meaning with the search for happiness, which is emphatically not the same thing. (Perhaps they get M. Russell Ballard’s Our Search for Happiness mixed up in their head? In any case, I regret to remind the reader that meaning and happiness are not synonyms). These students then make Victor Frankl their Exhibit A for how one can “choose to be happy,” even during the Holocaust.

But having actually read Man’s Search for Meaning once upon a time, I can testify that, guys, Victor Frankl did not actually enjoy the Holocaust! He found meaning in it, yes, and with it the strength and the resolve to survive and escape it, but he was still trying to survive and escape it! At no point in his book does Frankl ever say he was happy during the Holocaust. Not once does he turn to his fellow prisoners and say, “Welp, no use complaining about it, cheer up everyone, let’s choose to be happy!”, and then proceed to whistle a happy tune during slave labor, give a chirpy good morning nod to the SS Guard, plaster a smile on his face while he crapped his guts out with dysentery, and cheerfully skipped through an enforced death march in the snow without shoes–and when the Americans liberated Dachau, he didn’t say, “Oh no need to free us, for you see, I’ve chosen to be happy here, no matter where I am!” Serious, I do believe his fellow prisoners would’ve killed him if the SS didn’t first.

Frankl even explicitly says in the book that “happiness must ensue,” that is, one must have a reason to be happy. Frankl does not confirm but repudiate the rhetoric of “choose to be happy,” because happiness must result—you do not choose it. Now, one can perhaps choose to find some meaning in one’s life, and with it the wherewithal to not just survive but overcome, and even create the conditions by which happiness may eventually become possible, whether in this life or the next. But again, do not make the juvenile assumption that happiness is a choice. It is far grander than that. It is not a bag of chips on a grocery aisle, or a snack in a vending machine, or a shirt off the rack for you to just pick out and try on. (Mayhaps our American conflation between consumption and fulfillment explains in part why we are all such anxious, neurotic messes).

The irony is that, of all my students, the ones that were most genuinely charming, cheery, pleasant, interesting, intriguing, fascinating, kind and decent are the ones that have actually survived horrific tragedy–poverty and assault and oppression and abuse and so forth. I suppose one could then claim that these students are living proof that happiness is a choice, except that these were never the students who wrote me such dubious papers. They knew better. They’d suffered too much. Any happiness, peace, and/or contentment they had was hard-won, incomplete, and ensued from some other meaning they’d found in the midst of—and usually only after—the trauma and the tragedy. This same tragedy had fleshed them out, made a much fuller human being out of them, than the young ones who wrote about “choosing happiness,” who still did not yet know the meaning of either choice or happiness.

But I also tried to not be too hard on those papers when I got them; these students were merely too young, too inexperienced, to know better, is all. They didn’t need me to burst their bubble; as I had already learned from hard experience myself, life would show them all soon enough.