I had a working-class student once, when I still lived in Salt Lake, who recounted attending the funeral of a close childhood friend who had died of an overdose. An older woman came up to him while he was inconsolable and said, “Don’t worry, he’s in a better place now.” He snapped back: “Oh, so I’m not a better place? He’s better off without me, is that what you’re saying?!” In fairness to that nameless lady, she was likely trying in all sincerity to “mourn with those that mourn,” and so had (in the words of Joyce) cast about in her mind for words to console him, only to find “lame and useless ones.” She used a cliche because that’s all she had. But the sin wasn’t that she spoke a cliche, but that the cliche was thoughtless.

Per Mosiah 18:10, our baptismal covenants are first and foremost to “mourn with those that mourn, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort—” Such clearly indicates that our lives, even under the absolute best of circumstances, even the most disproportionately blessed, will be replete with mourning. The real test of our mortal probation, then, isn’t whether or not we will mourn (we have no hope of avoiding that), but only if we will use our mourning to mourn with others. If our sufferings haven’t made us more empathetic, generous, and charitable (without which, per Moroni, we are nothing), then we really will have suffered in vain, and set our baptismal covenants at naught.

But mourning with others is easier said than done, for the simple reason that no two people suffer in the exact same way. By way of example, I worked for years on a certain Book (as I have perhaps plugged a little too shamelessly) about how my mother died only two days after I got home from my mission. I wrote it partly with the hope that it might mourn with someone else who had suffered the same; I knew two other missionaries in Puerto Rico alone who lost their mothers, so I suspected that losing a parent while serving is much more common than we like to acknowledge.

Yet even then, my experience of mourning was not identical to theirs: both those other two missionaries lost their moms during their missions, not directly after. Comparatively, I had it easy, I suppose: I at least got to say goodbye. Even for three young men such as we with near-identical stories of loss, our experiences never perfectly synced up, nor did any of us mourn in the exact same way. We never stayed in touch or compared notes, in part because we couldn’t. Hell, for that matter, my experience of mourning wasn’t even identical to that of my own father, or my brother, who had to watch her whither away slowly, in real time, not all at once, like me; in the final tally, everyone had to grieve alone.

This isn’t to say it is impossible to “mourn with those that mourn”, only that it requires real creativity and real imagination (the root of empathy) to mourn with others effectively, without falling into cliche and therefore thoughtlessness.

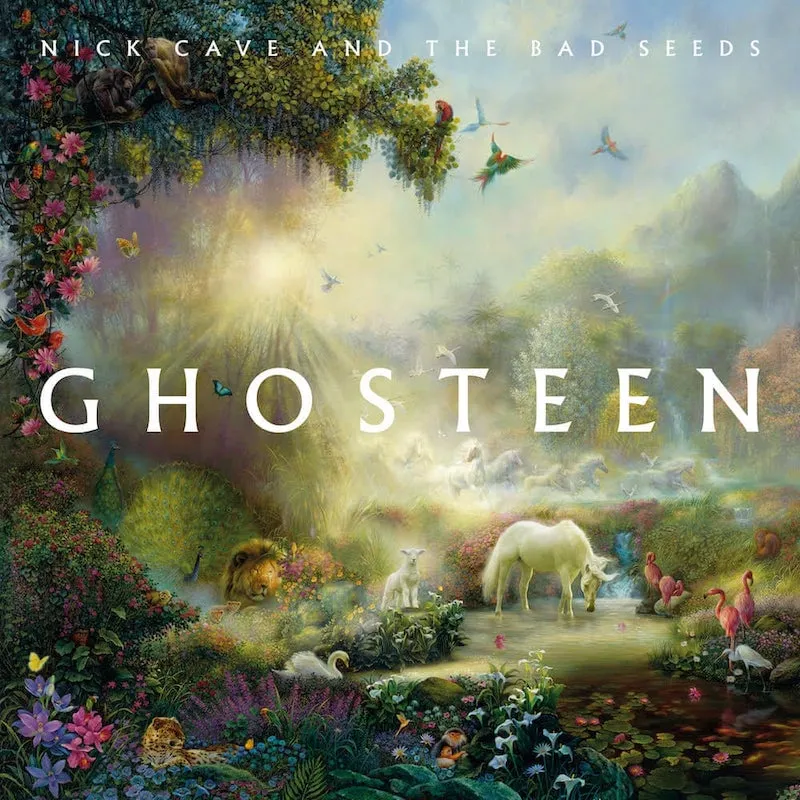

This has been a long, roundabout way of explaining why my ears always perk up when someone actually tries to mourn in a sincere and novel manner. My latest example of the same is Ghosteen, the nigh-universally-acclaimed 2019 album by those old Post-Punk veterans Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. An ambient/electronic double-album, it was released only four years after the accidental death of Nick Cave’s teenage son in 2015, while he was out climbing the cliffs of Brighton, UK. Cave’s previous album, 2016’s Skeleton Tree, was mostly completed when he learned the awful news, so he was only able to make a few oblique, last-minute lyric changes to the record to address his loss. It was on Ghosteen, then, that Cave finally got to fully process his grief.

Musically, Ghosteen is light-years removed from the Bad Seed’s Punk Rock of the ’80s, though it was not without precedent: Cave had been trying his hand at quieter ballads since the ’90s (especially on 1997’s critically-acclaimed The Boatman’s Call), and had already been experimenting with ambient and electronica since 2013’s Push Away the Sky. For that matter, even back in their ’80s hey-day, the Bad Seeds were renowned for obsessively exploring themes of death and loss: from their Gothic 1984 debut From Her to Eternity to their 1988 death-row anthem “The Mercy Seat,” they never shied away from what Nibley called “The Terrible Questions,” of what happens to us when we die, or why we must even die in the first place.

Yet there had also always been something a little too performative and theatrical about those earlier songs, hadn’t there–not that Nick Cave wasn’t ever sincere, only that he and his band-mates engaged with death the way most young people do: as something mysterious and dark and distant, not as a close and constant and ever-encroaching companion. By 2019, however, a late-middle-aged Nick Cave was sadly on much more intimate terms with grief and mourning, and Ghosteen reflects that maturity.

The strong religious thread permeating Nick Cave’s music is also of interest here: Cave after all is who opened The Boatman’s Call with “I don’t believe in an interventionist God”–which nevertheless indicates that he still believes in a God of some sort. His first band The Birthday Party had an album called Prayers on Fire. And of course on his signature-song “The Mercy Seat,” Cave finds easy analogy between the electric-chair and the Ark of the Covenant, since “God is never far away” from each. All the religious imagery permeating his oeuvre does not appear to be affectation, he really does seem to be wrestling with his faith sincerely and incessantly; if he could never fully buy-in to organized religion, he could never fully leave it alone, either. He is ambiguous about religion in the full, original sense of the word: of honestly not being sure about it one way or the other.

He brings that same ever-unresolved ambiguity to the fore on Ghosteen, where there are no tidy narratives, no trite re-assurances, no ultimate resolutions as he processes his bottomless grief. Ambient turns out to be the exact right genre for Ghosteen, because, like grief itself, it is a form with neither climaxes nor completions, neither crescendos nor culminations. Both lyrically and musically, on both the individual tracks and across the album entire, Ghosteen actively resists resolution. Think Ecclesiastes without the final chapter, or a Book of Job that ends at chapter 37, or a D&C 121 that stops at verse 6, or a Book of Mormon sans the Book of Moroni.

Don’t get me wrong, there are certainly still moments of transcendence on the album; for example, on the long title track that opens disc two and starting at about the 5-minute mark, there is this moment of sheer unabashed beauty and aching sincerity (and I mean that in the best way possible), as though Cave were communing with his dead son directly and his grief was at last coming to an end. “A ghosteen dances/In my hand,” he sings with deep emotion, “Slowly twirling, twirling, all around…” Tellingly, however, the feeling only lasts a minute or two; the song, as well as the whole rest of the album, just keeps on going long after that moment of euphoria, as he quietly reverts back to his previous brooding. It is representative of the grieving process generally, where even our moments of joy and peace are still mired in all this endless vexation. Grief may eventually dissipate, but it never fully disappears.

Not that this album is ever dark or depressing, mind you; depression is not the same as grief. Depression is when you feel life isn’t worth living; grief by contrast is when you realize too late that it is worth living (“This world is beautiful/Held within its stars,” is how he opens that same title track), which makes the fact that life must still end anyways all the more vexing. It is the primary function of religion and philosophy to somehow resolve this vexation; but “mourning with those that mourn” does not lie in the resolution, but amidst the vexation itself. Indeed, the vexation itself can even be a source of peace: just as there is still immense peace and comfort to be found in all those aforementioned scriptures without ever reaching the final resolution, there is still immense peace and comfort to be found in Ghosteen. The Thomas-Kinkade-style cover-art appears to be entirely sincere.

That is because there is comfort to be had just in knowing we are not alone in our grief—that even if no two people have ever suffered identically, that we have all nevertheless still suffered together. The way you properly mourn with those that mourn isn’t by tritely trying to resolve their mourning, but by acknowledging its confounding irresoluteness. It’s why “I’m so sorry for your loss” will always be better than “They’re in a better place now.” Such is how we fulfill our baptismal covenants.

*****

I also, admittedly, have an academic interest in Ghosteen, because the -een suffix is of Irish Gaelic origin, and signifies something small and therefore benign and beloved—fitting, since Cave here is addressing the ghost of his own child. I wrote my dissertation and first book on Irish and Latin American literature, you see, wherein I argued that writers from these two regions deploy much more sympathetic portrayals of the dead than English and Anglo-American writers, who typically portray the dead as either horrific monsters or illusory frauds.

The short of it is that, for a variety of Calvinist reasons, Anglo-Protestants tend to despise any population they deem economically unproductive–it’s why Americans have such cruel anti-homeless laws, it’s why we so consistently slander Mexican migrant workers and the impoverished generally as “lazy freeloaders” against all available evidence, it’s why we jail the poor yet let “the guilty and the wicked go unpunished because of their money”–and by definition, there is no population more economically unproductive than the dead. Hence why ghosts in Anglo media are either portrayed as monstrous horrors that must be exorcised and exterminated (which is the brilliant joke behind Ghostbusters), or as obvious frauds that must be swiftly debunked (the arc of every early Scooby-Doo episode). There’s a reason why the old Hannah-Barbara cartoon had to specify that Casper was a friendly ghost, just as the Anglo-Australian Nick Cave has to specify that he is singing to a Ghosteen: our default is always to assume the ghost is dangerous till proven otherwise.

But predominantly-Catholic Ireland and Latin America, by contrast, have no prior commitment to Anglo-Protestantism, and hence have always engaged with the dead on much more friendly terms (it’s why Halloween comes from Irish immigrants, and Day of the Dead from Mexico). Indeed, they’ve had to of necessity: given how often the Irish and Latin Americans have been subject to large scale extermination attempts by both the U.K. and U.S. respectively, these populations have needed all the allies they can get. This friendliness towards the dead is itself a form of resistance: for in affirming the intrinsic value of the dead, Irish and Latin American writers also affirm the intrinsic value of the living.

Nick Cave’s decision to entitle his 2019 album Ghosteen, then, with the Irish suffix, is also an implicit rejection of the pernicious Anglo-Protestant assumption that only the so-called “productive”–whether dead or alive–deserve to exist. Indeed, the value of a human being should never be based upon our “productivity” at all, but on our sheer existence. “The worth of souls is great in the eyes of God” reads our own D&C 18:10, affirming that the Almighty values us not for what we can do for Him (we are all “unprofitable servants,” after all), but simply for who we are–as we should all likewise value each other, both the living and the dead.

As I have written before, all of LDS doctrine itself likewise declares that the dead are neither intrinsically scary nor illusory as well. We are repeatedly taught that the veil is thinner than we realize; that the dead move upon us “with the spirit of Elijah;” that our hearts must turn towards them as theirs do towards us; that it is our work and our glory to redeem the dead in God’s holy temples; that even the Book of Mormon, the keystone of our religion, is as a voice “whispering out of the dust,” brought forth by the resurrected dead who (like the revenants of Irish and Latin American literature) have been erased from history but are not silenced, and will return.

Hence why we are taught so religiously to do work for our dead: Invariably, we all end up treating the living the same way we treat the dead, and vice-versa. That is, another way we must “mourn with those that mourn” is to treat the living with the same inherent respect we should’ve been treating the dead all along. Whosoever hath ears to ear, let them hear.