The appeal of the first John Wick in 2014 was in the brilliantly stupid simplicity of its premise: rather than have the protagonist go on rampage against the mob cause they killed his wife or girlfriend or what have you (as has been the plot of more interchangeable revenge-fantasies than can be here listed), the hero goes on rampage cause they killed his dog. The whole flick is still obviously a revenge-fantasy; but whereas the murder of a lover would have provoked yet another weary round of debates on the cycle of vengeance and women-in-refrigerators and the proto-fascist tendencies inherent in the genre and so forth, the death of a dog immediately gets the entire audience on the side of the killer. Absolutely everyone–from the most bleeding-heart liberals to the sincerest turn-the-other-cheek Christians and everyone in between–instinctively demands that the dog-killers be executed as swiftly as possible. The death of a human being we debate; the death of a dog, never.

Of course it was never just a dog. As John Wick very explicitly lays it out in the first film (such that even the slowest audience member won’t miss it), that cute little dog represented his recently-deceased wife–that is, the whole reason he quit the hitman profession in the first place–and more importantly the possibility of redemption. Yet as the various mafiosos and contract-kilers he encounters throughout the film warn him, there is no redemption in this line of work: his hands are too bloody. (To quote our own Doctrine and Covenants 42:18, “Thou shalt not kill; and he that kills shall not have forgiveness in this world, nor in the world to come.”) He was always going to come back, simply because he could never truly be cleansed of his sins in the first place.

Now, the John Wicks are not really all that philosophical of films; their primary raison d’etre is to set up a series of fun action set-pieces that somehow combine realistic gun violence with stylishly dreamlike tableaus, not meditate on the nature of morality or whatever. They become fairly ridiculous the moment you think about them, which you are clearly not intended to.

The sequels suffered from the same bloat that most sequels do: e.g. expanding the world building from the peripheries to the main plot; turning bit characters into main characters; constantly trying to top the already-over-the-top set-pieces of whatever the previous film was; sometimes forgetting to just be plain fun, and etc. Yet throughout the first three films, the impossibility of real redemption remains the common through-line of the various plot threads. Indeed, one could argue that the John Wick films, even at their most stylishly empty-headed, ultimately present for us what a world without the Atonement looks like.

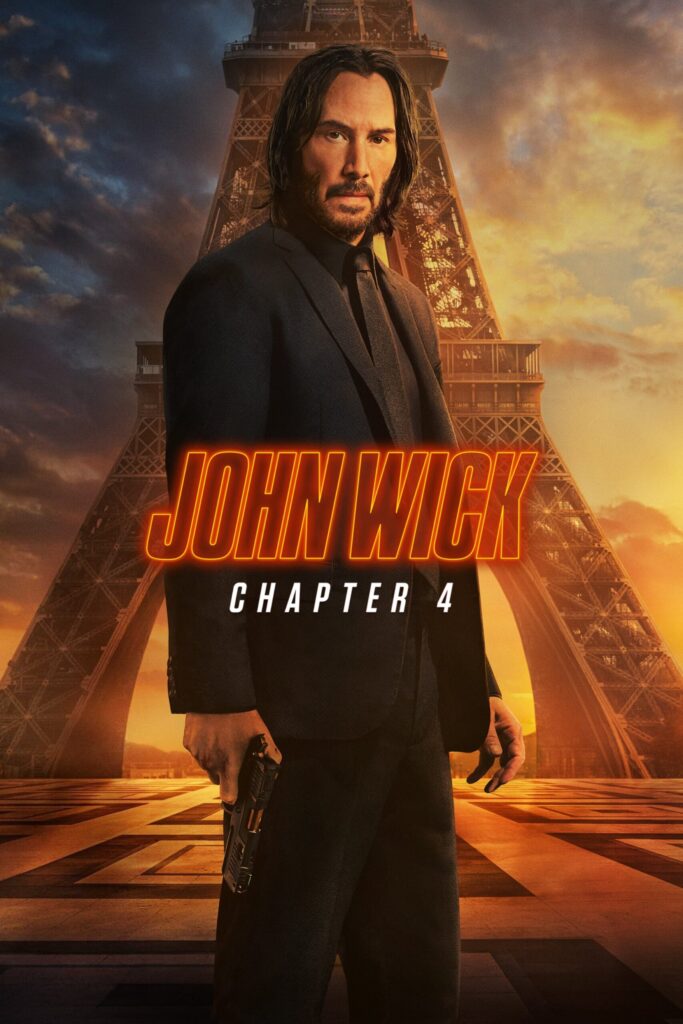

The fourth and final film, however, does manage to shake things up a bit–at least theologically. Here, Hong Kong action-star Donnie Yen plays a blind-yet-deadly hitman hired to take out John Wick once and for all. A former friend of Wick himself, Yen’s character is made sympathetic in his own right, when the audience learns early on that he has been forbidden by the mafioso “High Table” to ever get close to his adult daughter, under pain of death for them both. Nevertheless, a sadistic French Marquis representing the High Table promises Yen that he will end his exile from his own progeny if he comes out of retirement himself and kills John Wick. Yen reluctantly agrees.

Without getting into the convoluted mythology and silly plot-details, the film culminates with a duel at 10 paces between Wick and Yen, held at dawn, in front of the famed Sacré-Cœur Church in Paris. If Yen prevails, he will be liberated from his obligations to the High Table and be reunited with his daughter; if Wick prevails, he too will be liberated from the High Table, and his friend Winston will have his rights and privileges restored. No matter who wins, someone else’s story ends in unbearable tragedy; once again, no true redemption is possible.

Or is there? This scene takes place in front of a Church, after all. And what does John Wick do? He lets himself get shot and mortally wounded by Yen. When the Marquis eagerly steps forward to deliver the final shot and coup-de-grace, Winston chides him–calls him “You arrogant asshole”–noting that Wick still has not fired. Wick promptly shoots the vicious Marquis in the head. All conditions met, the presiding High Table representative announces that Yen is free to reunite and reconcile with his daughter, while Winston’s life and privileges are restored. Wick passes away in great pain yet also at peace, to be reunited with his wife in the next life–he might as well have said, “It is finished.”

Cause what exactly happened here? Wick died to save his friends, and in his death conquered the power of the wicked one. He has facilitated a reconciliation, returning the hearts of the children to the fathers and the fathers to the children, and satisfied the demands of justice. That is, he has completed an Atonement of sorts, dying for the sins of others. The Christ figure is one of the hoariest old tropes in art and literature, but the John Wick series, after 4 films of increasingly ridiculous bloat, still managed to find a fresh way to enact it. May we go forth and do likewise.