Today marks the release of The Mysteries, Bill Watterson’s first new book of, well, anything, since Calvin and Hobbes wrapped up its nigh-universally beloved newspaper run clear back on New Years Eve 1995. We should have a review up of The Mysteries soon; but in the meantime, given how Calvin and Hobbes collections were still for sale at the BYU and BYUI bookstores well over a decade after the strip concluded, I also think it an apropos time to revisit just what was it that made this comic about a wildly-disobedient, agnostic child so popular with the same Gen X and Millennial Mormon kids who were taught to sing “Reverence is more than just quietly sitting…”

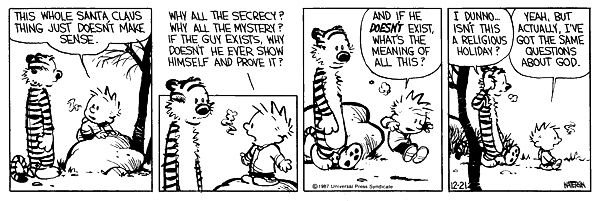

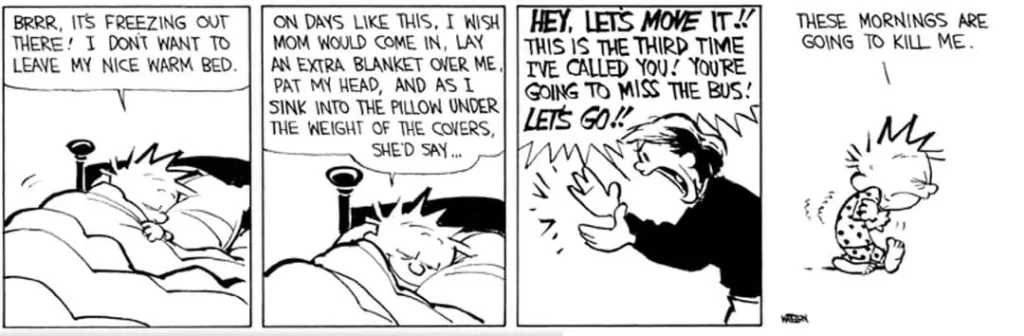

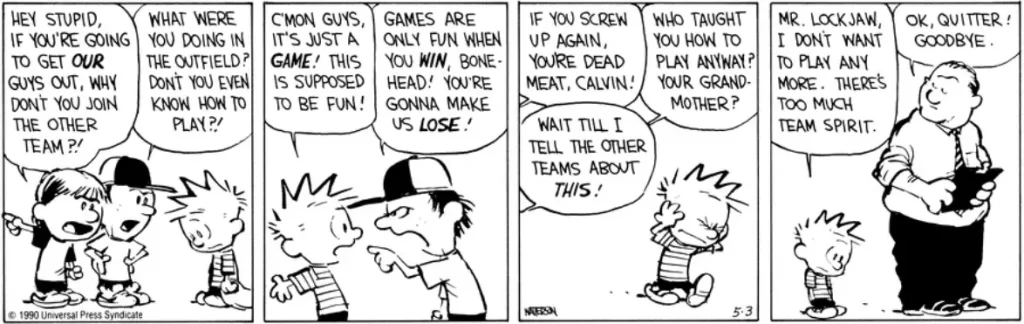

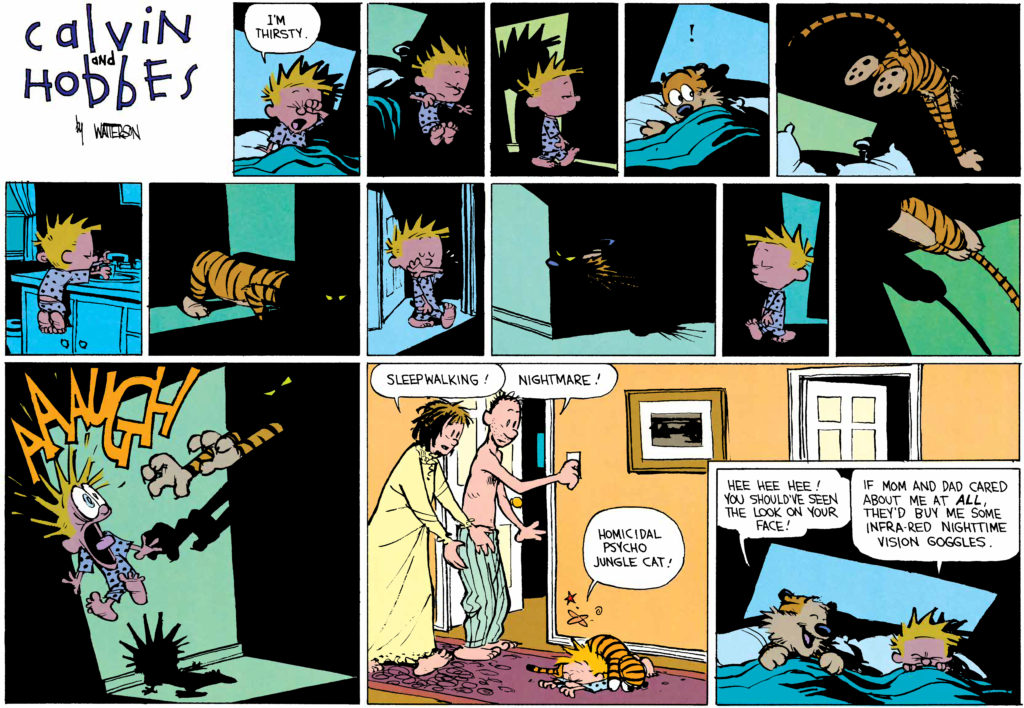

Of course, Calvin’s radical disobedience was itself part of the appeal: in a conformist heavy culture like ours, replete with numerous dietary, media, Sabbath, and fashion prohibitions, wherein “obedience is the first law of heaven”, Calvin vicariously expressed what so many of us could only dream of doing. (Certainly the comics where Calvin hates getting out of bed resonated with me more, not less, once I started early-morning Seminary).

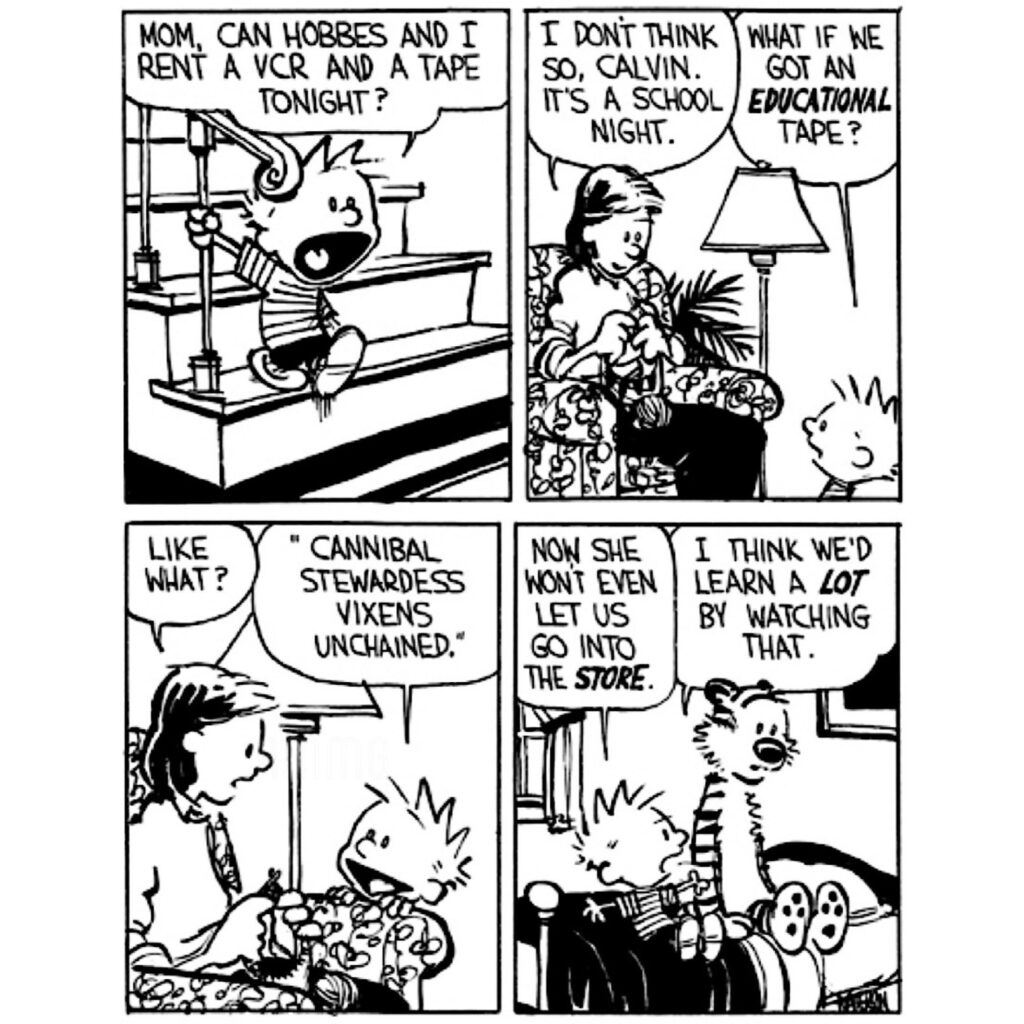

If we weren’t allowed to watch R-rated movies or The Simpsons (at least, not till we got better at hiding it), we could at a bare minimum sneak in a G-rated Calvin and Hobbes comic from the Funny Pages; it was a sort of squeaky-clean rebellion.

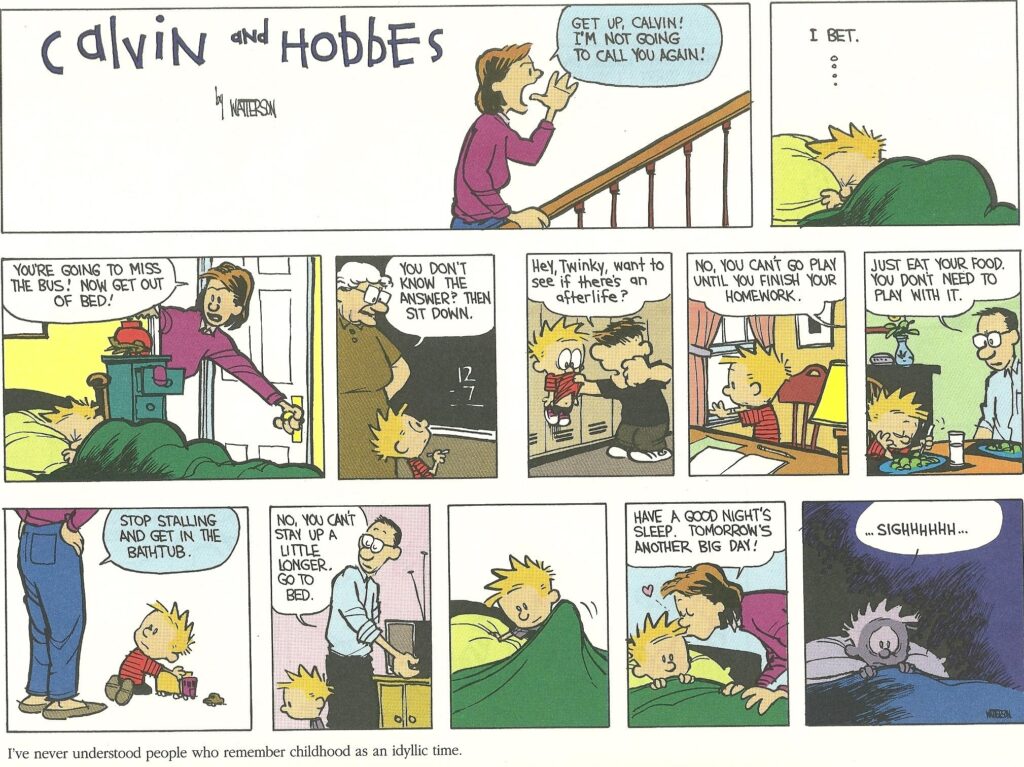

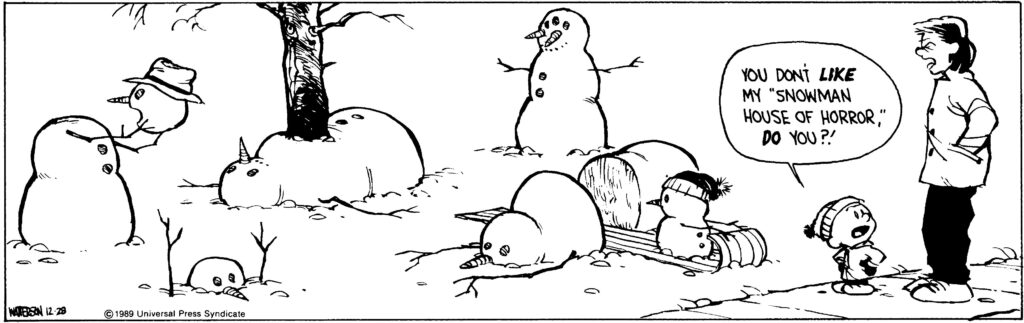

Of course, just about everyone loved the vicarious rebelliousness of Calvin and Hobbes, regardless of religion, age, or creed; there was nothing uniquely LDS about that. But it wasn’t just the childhood rebellion that appealed to us all, no–it was also the sheer fact that Bill Watterson actually remembered what it was like to be a child!

Such is a rare gift; I recall reading somewhere that Fred Rogers of Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood fame could also still recall his childhood–hence why he was in turn so good with children. Watterson similarly does not romanticize or idealize childhood; thus he could express what it actually feels like to be a child, in all of its agonies and passions.

We’ve always just been a touch suspicious of Mosiah 3:19, haven’t we–“become as a child, submissive, meek, humble, patient, full of love, willing to submit to all things which the Lord seeth fit to inflict upon him, even as a child doth submit to his father”–which has led more than a few young LDS parents to exclaim in exasperation, “children are submissive, meek, humble, patient?? Since when?!“

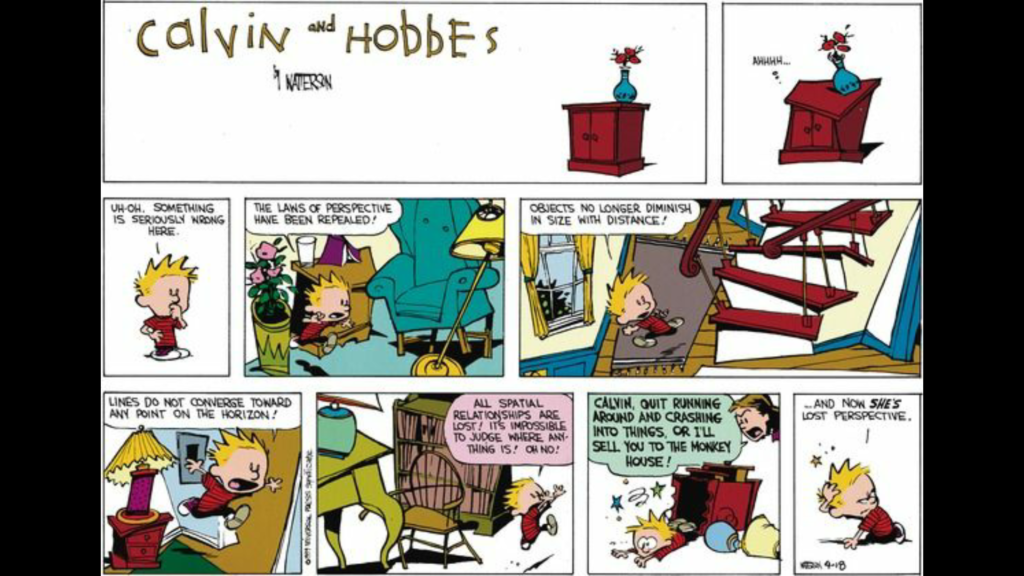

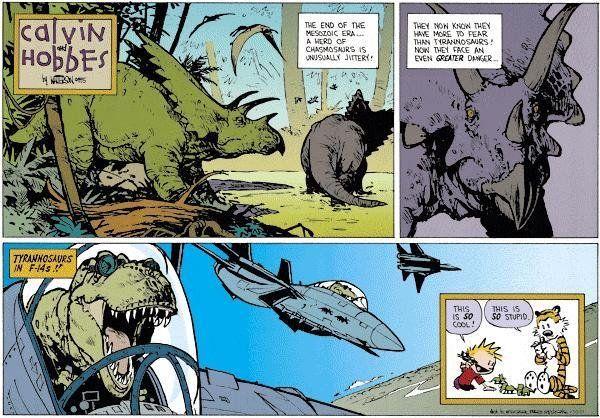

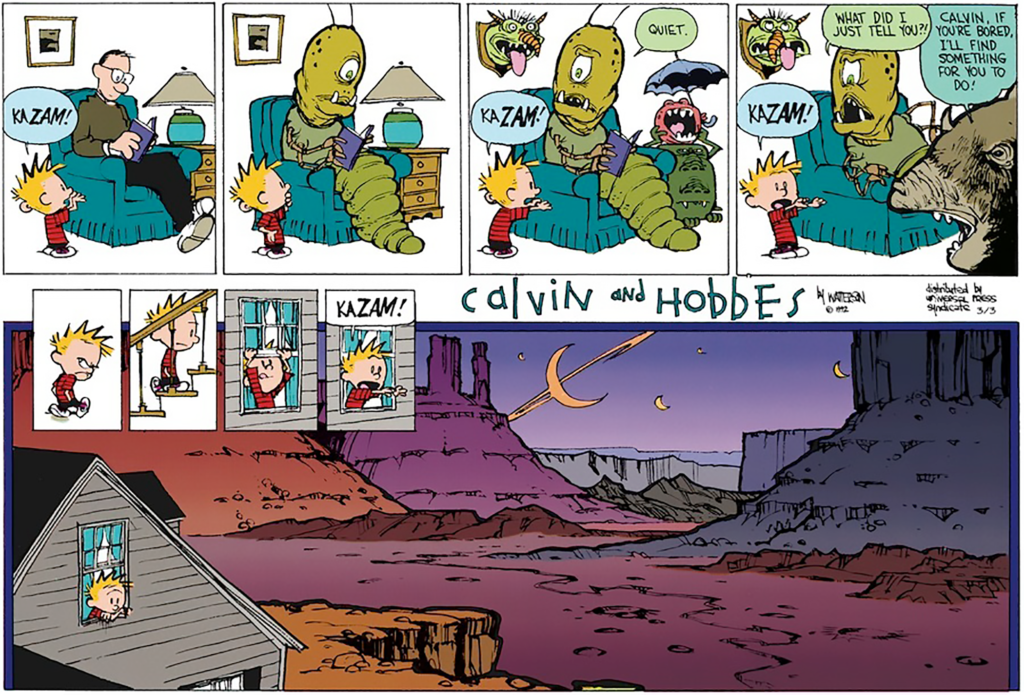

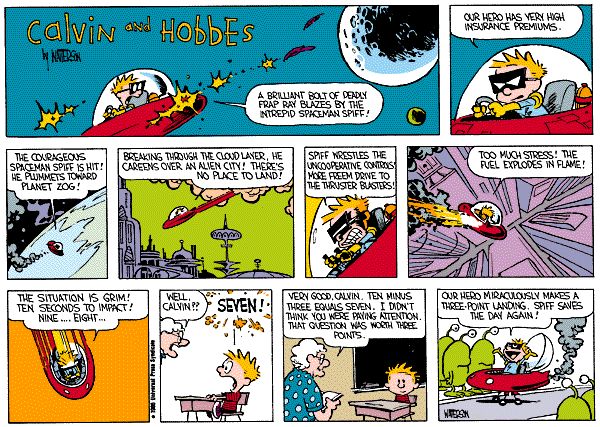

Nevertheless, the Savior meant it when He said, “Verily I say unto you, Except ye be converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven” (Matt. 18:4), and it is vital that we understand precisely what “be as a little children” actually means. And indeed, what Calvin and Hobbes reminds us, repeatedly and explicitly, is that what children have in abundance–and which they largely lose by adulthood–is imagination.

Imagination isn’t just necessary as a coping mechanism against the horrors of the world or for thinking outside the box at work or whatever, no: Imagination is absolutely essential for empathy–that is, to literally imagine what it might be like to be someone else. Imagination is therefore how one fulfills the commandment to “do unto others as ye would have them do unto you”, which is only possible if you can imagine what others would like to have done unto them in the first place. That is, imagination is how one gains charity, the pure love of Christ, without which ye are nothing. Imagination is how one “might with surety hope for a better world”–precisely because we can imagine a better world–which “maketh an anchor to the souls of men” (which, given the current state to the world, matters now more than ever).

But even that’s not the main reason Calvin and Hobbes resonates with us–or at least with me.

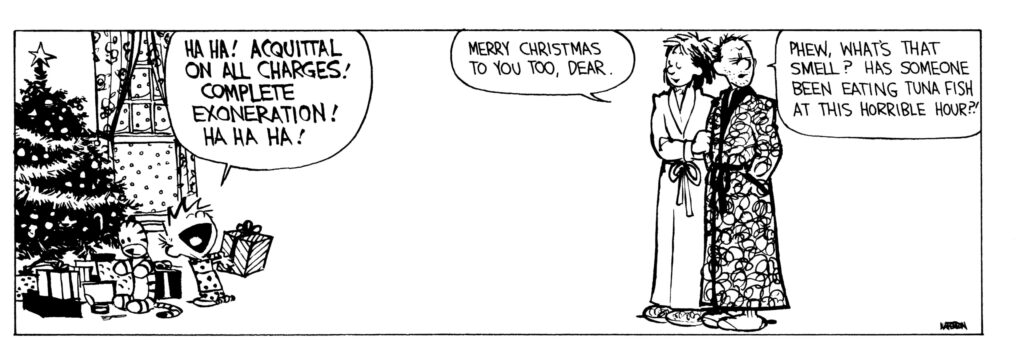

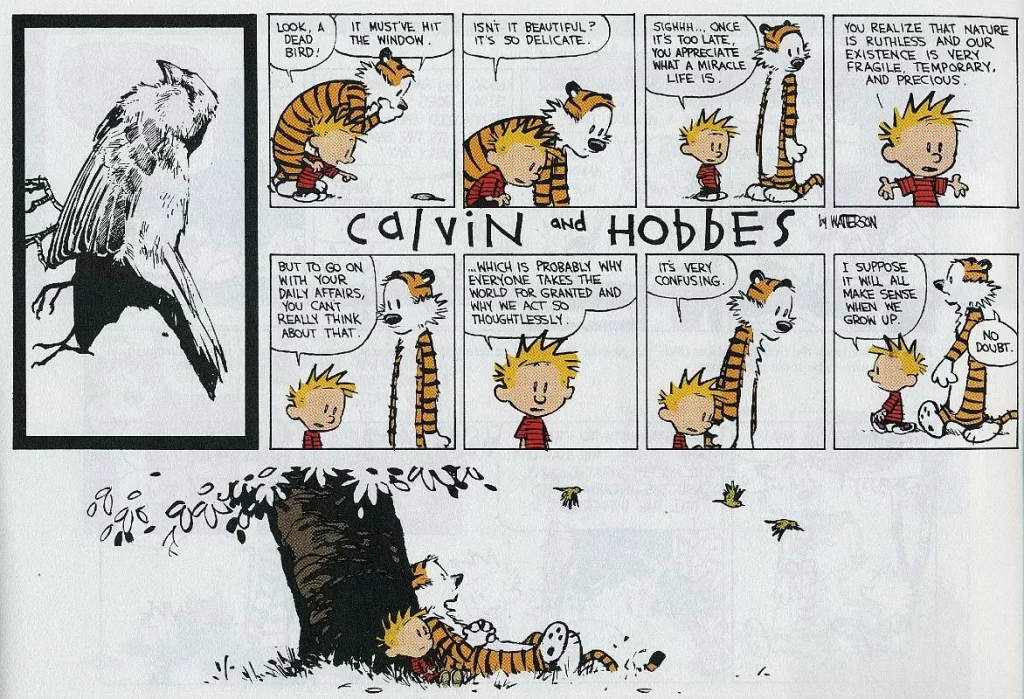

Several years ago, as a full-grown, gainfully-employed, college-and-grad-school-educated adult, I got the Complete Calvin and Hobbes boxset for Christmas. I stayed up till 1:30am re-reading them, for the first time since a small child in the ’90s.

I had just the slightest fear that this comic would be yet another artifact of youth that failed to live up to my most primordial memories, leaving me yet again feeling disconnected from my childhood and myself. Utterly unfounded fears. If anything, I laughed with, appreciated, and adored this cartoon even more thoroughly than I did as a child (and that’s really saying something). I quickly moved on from mere relief to awe at the brilliance of this comic’s childlike simplicity.

The buzz I felt that Christmas night was akin to the first time I read Catch-22 at 17 or Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance at 24 or Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia at 27; or when I saw the Mona Lisa in person at the Louvre, or saw The Shawshank Redemption for the first time on cable TV as a teenager; or the first time I listened–really listened–to the Beatle’s Abby Road, U2’s Joshua Tree, or Arcade Fire or Animal Collective or Debussy; or when I saw the sun set on the Guajataca in Puerto Rico, or the fog rise from Yellow Mountain in China…

Yet Calvin and Hobbes predated all these experiences; and it was both humbling and exhilarating to realize that everything I’ve ever thought, felt, or valued,–everything I learned in college, grad school, and life in general–about materialism, art, philosophy, representation, semiotics, the Protestant work ethic…

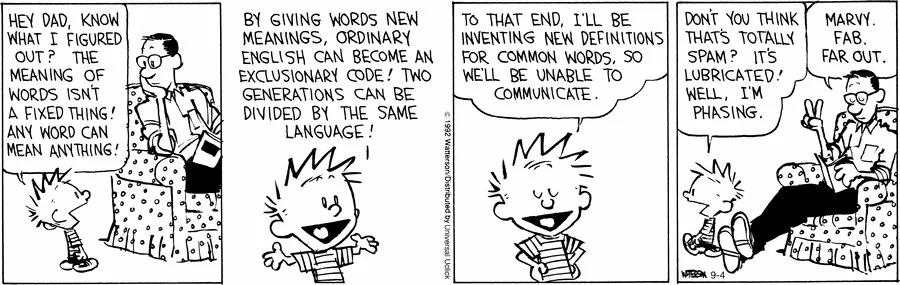

…the innate worth of souls, goods of first and second intent, the sublimity of passion, Emersonian whims, the revolutionary potential of romance, the power of language, the wildness of words…

…as well as the hugeness and incomprehensibility and grandeur of mother nature and the universe entire, the uncharted possibilities of existence and imagination, I first encountered as an impressionable youth on these newspaper comic pages.

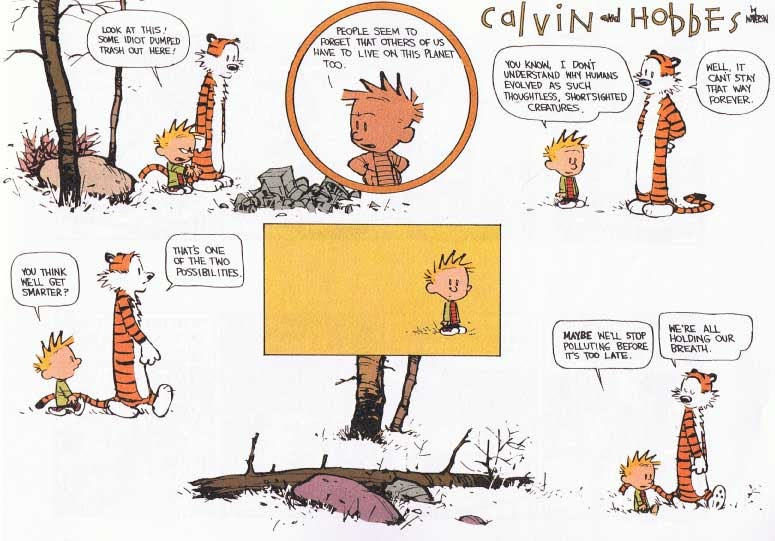

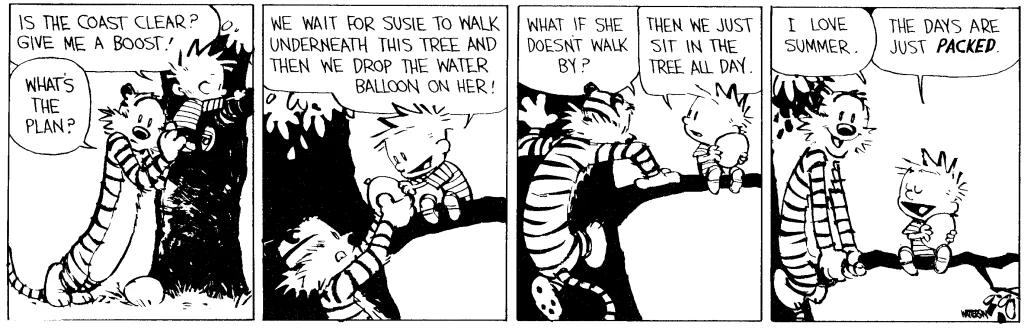

And what is more, Bill Watterson was that ultra-rare individual who really did seek not for riches but for wisdom. Like, for reals! He never licensed Calvin and Hobbes for TV specials, or merchandise (all those Calvin pissing on Ford or Chevy logos–or worse, praying before a cross–are utterly unsanctioned and a violation of the eighth commandment), T-shirts, plush-dolls, or whatever. He could’ve, mind you! Could’ve made himself a very wealthy man! Charles Schultz did it, Jim Davis did it, Gary Larson did it, Cathy Guisewite did it, Scott Adams did it, etc. and etc. Cartoonists cashing in on their creations was always just part of the hustle. Yet still Watterson fought the comic syndicates tooth and nail to prevent crass commercialism from cheapening the magic of Calvin and Hobbes. He knew what he had, and valued it above riches.

It’s comforting, rejuvenating, and frankly incredible to consider that, within my own lifetime, there was a bona fide popular artist who refused to dumb down, who never sold out–and meant it–who consciously went out on top on his own terms, who openly critiqued our destructive consumerism and pretentious posturing in the face of the terrible questions, and did so without condescension, without smug self-satisfaction, but rather with a childlike and wondrous joie de vivre.

We all pay lip service to seeking not for riches but for wisdom (especially in our faith), but how many of us ever actually do that? The lessons are always for other people, aren’t they; absolutely none of us internalize a contempt for riches within ourselves. The idea that we ourselves could also seek not for riches but for wisdom seems almost incomprehensible to us, as alien as the surface of Mars. But Bill Watterson, blessedly, reminds us that such things really are possible!

I loved Calvin and Hobbes as a child; but now in my middle years I stand back in absolute wonder of Bill Watterson’s achievement, at the utter rarity that was this jewel of a comic–one that both fulfilled and transcended its medium–and how profoundly blessed I was to encounter this strip in its first run, while still a child itself, when it could still enrapture my imagination in youth.

Maybe I’m overselling the comic right now, maybe my reflections are more tinged with nostalgia than I’m conscious of or care to admit, maybe it’s best to approach this cartoon on its own terms and not with any over-hyped promises of grandeur from me–no matter. David Markson wrote in Wittgenstein’s Mistress that he could imagine a world without people easier than he could a world without Mozart; I, too, can picture the world ending easier than I can a world without Calvin and Hobbes.