What could have possibly prompted Bill Watterson to break his J.D. Salinger-esque hermitude and publish his first new book in a quarter-century?

To recap: ever since Watterson abruptly ended Calvin and Hobbes at the absolute peak of its popularity in 1995, he has steadfastly refused any and all calls to return to the drawing-board. An intensely private man, he has stridently avoided the book-tours, book-signings, and talk-show circuits that most authors would’ve killed to go on. Every reporter and researcher that’s gone in search of him has returned empty-handed. He’s achieved Thomas Pynchon levels of reclusiveness.

Moreover, in the few-and-scattered interviews[1]Like, I think there have been five total since 1996 he has consented to give in the intervening decades, Watterson has not once expressed the slightest regret for ending the strip when he did; has repeatedly affirmed that everyone clamoring for his return would be begging him to quit by now if he’d kept it going[2]Given what happened to fellow-’90s mainstay The Simpsons, he has a point; and has turned down every lucrative offer to monetize the comic further.

Hence there have been no Calvin and Hobbes TV shows, movies, or Holiday specials, no Hobbes plush-dolls or Spaceman Spiff action figures, no posters or calendars or greeting-cards or bobble-heads or Lego sets or Happy Meal toys or fridge magnets or other assorted tchotchkes. Not even Charles Schultz was able to resist those temptations![3]To say nothing of Jim Davis or Scott Adams or…

But Watterson really did reject all merchandising opportunities; every Calvin and Hobbes t-shirt or Calvin-pissing-on-a-hated-car-logo (not to mention that insipid Calvin-kneels-before-the-cross) window-sticker you’ve ever seen is a brazenly unauthorized piracy. Watterson was that ultra-rare American–hell, that ultra-rare human being–who was sincerely, genuinely, motivated not by money but by art. He had zero interest in ruining the comic’s magic through either forced-longevity or crass-commercialism, so he did neither, no matter how much money he left on the table. We talk a lot about “seek not for riches but for wisdom”[4]D&C 11:7, but Watterson actually did it.

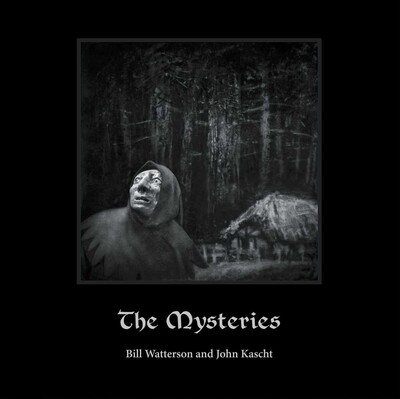

He’d ended Calvin and Hobbes because he’d exhausted its possibilities and run out of things to say; it follows therefore that he wasn’t going to publish something new till he finally had something else worth saying. And for nearly 30 years, he didn’t! It was entirely natural to presume that he would pull a Harper Lee or Ralph Ellison or J.D. Salinger[5]Who were also all authors of disaffected youth, come to think of it. and never willingly publish anything new again. What was it, then, about The Mysteries–his brand new “fable for grown-ups”, produced in “unusually close collaboration” with acclaimed illustrator John Kascht–that he felt was at last worth sharing with the world? (Because given how radically this art style differs from his old M.O., it certainly wasn’t to capitalize on Calvin and Hobbes fandom…)

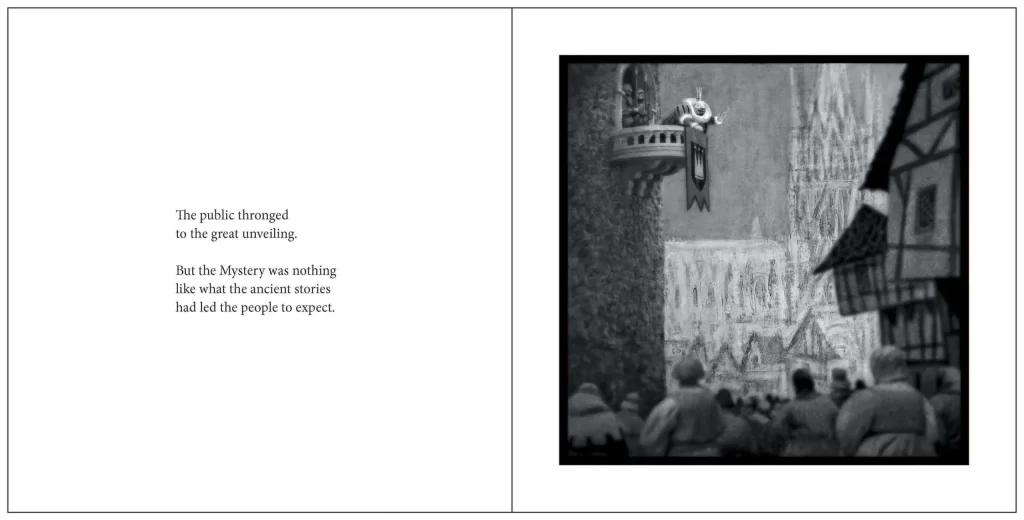

The artwork is of course excellent; we already knew Bill Watterson could really draw when he felt like it (see for example his spot-on parodies of superhero comics, detective comics, pulp realism, and even Cubism in Calvin and Hobbes), though how much of The Mysteries is Watterson and how much is John Kascht is unclear. The book entire is also a mere 72 pages long–only half of which are the actual illustrations (the other half is the very simplistic story-text, as seen below)–so it’s not like he’s releasing a massive backlog of artwork or long-simmering poetry here. (This isn’t Paul Valéry’s La Jeune Parque, in other words.)[6]Heck, we also already knew that Watterson could write metered poetry when he felt like it, but The Mysteries isn’t written as a poem, either.

So again, I circle back to the question of: Why did Watterson select this book, at this time, of all things, as the long belated followup to one of the most beloved comic strips of the 20th century? As much as I would prefer to engage with The Mysteries strictly on its own merits, that simply isn’t possible when one of the authors is a mercurial recluse of the stature of Bill Watterson.

My interest in The Mysteries is two-fold: first and foremost, obviously, is sheer, shameless nostalgia. As an overly-imaginative child of the 1980s, I was the exact right age for the original run of Calvin and Hobbes to sweep me off my feet and resonate on a bone-deep level. The strip in fact ended when I was 12 years old–that is, right on the cusp of puberty–such that its ending also seemed to bluntly demarcate the end of my childhood (which was a little on the nose, if you ask me). Seeing Bill Watterson re-emerge from the shadows for the first time since the Clinton administration was always going to put me in a Proustian reverie, for all the years lost and time wasted[7]The title to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time in the original French, remember, carries connotations of not just time lost, but wasted.

I do not write “wasted” off-handedly. Because even bracketing away my childhood nostalgia for a moment, I have also been anxiously awaiting The Mysteries because I specialized in Modernist literature[8]Roughly, the works written in the lead up to, and in between, the World Wars during my English PhD program; and the premier poem of that period is T.S. Eliot’s 1922 magnum opus The Waste Land. Eliot’s own footnote informs the reader that “the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the poem were suggested by Miss Jessie L. Weston’s book on the Grail legend: From Ritual to Romance.”

Specifically, Eliot draws from Weston’s research into the Medieval legend of the Fisher-King, wherein a mysterious curse has fallen upon the land–the crops will not grow, the cattle die, the children are still-born–laying all things waste; so a knight of the Round-table is dispatched on a quest to find the elusive and mysterious Fisher-King, which will somehow break the curse upon the wasteland.

Though Medieval in imagery, Eliot’s poem was thoroughly Modern in sentiment, and deeply-reflective of his own post-war, post-pandemic (WWI and the 1918 Spanish Flu) historical moment, a time when the world was increasingly fractured, traumatized, alienated, politically-polarized, wasted, and swarming with resurgent authoritarian movements.

And now, exactly 101 years later, we have the retro-Medievalism of The Mysteries, whose Simon & Schuster marketing materials describe as follows: “a long-ago kingdom is afflicted with unexplainable calamities. Hoping to end the torment, the king dispatches his knights to discover the source of the mysterious events.” That is, we once again have a Medieval knight traversing the waste-land in our own post-war, post-pandemic (Iraq/Afghanistan and the 2020 coronavirus) historical moment, a time when the world is increasingly fractured, traumatized, alienated, politically-polarized, wasted, and swarming with resurgent authoritarian movements. This does not feel coincidental!

Indeed, upon further reflection, it suddenly makes perfect sense why Watterson–whose Calvin and Hobbes was staunchly anti-bullying, anti-climate-change, anti-pollution, anti-arms-proliferation, anti-xenophobia, anti-arrogance, anti-greed, anti-materialism, etc.–might take a gander at our present world and determine that his silence was no longer a virtue, that it was long past time to pipe up and say something, anything, even if only to help us process our collective angst.

Without spoiling anything (because this brief book really is best approached cold–though it is also eminently re-readable), let me here observe that Watterson’s aforementioned pro-environmentalism, anti-xenophobia, and anti-materialism remains on full display in The Mysteries; so, too, is his old Calvin and Hobbes belief, unimpaired after all these decades, in the salvific necessity of imagination. Like T.S. Eliot, he “[sits] upon the shore/Fishing, with the arid plain behind me.” He, too, is trying to traverse our modern waste-land in search of something, anything, to break the curse. Such, I suspect, is the germ and root of The Mysteries.

Let us hear the end of it: I have spent the past 6 months awaiting the release of The Mysteries with great fear and trepidation, because what could possibly live up to Calvin and Hobbes? At the risk of back-handed compliment, I can with relief declare that The Mysteries exceeded my modest yet anxious expectations. I found it profoundly affecting, and packs an emotional gut-punch, in ways I didn’t anticipate. Its finale reminded me immediately of Moses 1:10–“For this cause I know that men is nothing, which thing I never had supposed”–as well as Helaman 12:7–“O how great is the nothingness of the children of men; yea, even they are less than the dust of the earth”–and shares with both passages the equally peculiar conviction that our great nothingness is in fact cause for great comfort, not despair.

This strange little book is a timely reminder that our allegiances should have been with the Mysteries all along, not this failing and fallen world. It was the one message that was worth Bill Watterson breaking his long silence for, because it is our only way out of the wasteland.

References[+]

| ↑1 | Like, I think there have been five total since 1996 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Given what happened to fellow-’90s mainstay The Simpsons, he has a point |

| ↑3 | To say nothing of Jim Davis or Scott Adams or… |

| ↑4 | D&C 11:7 |

| ↑5 | Who were also all authors of disaffected youth, come to think of it. |

| ↑6 | Heck, we also already knew that Watterson could write metered poetry when he felt like it, but The Mysteries isn’t written as a poem, either. |

| ↑7 | The title to Proust’s In Search of Lost Time in the original French, remember, carries connotations of not just time lost, but wasted |

| ↑8 | Roughly, the works written in the lead up to, and in between, the World Wars |