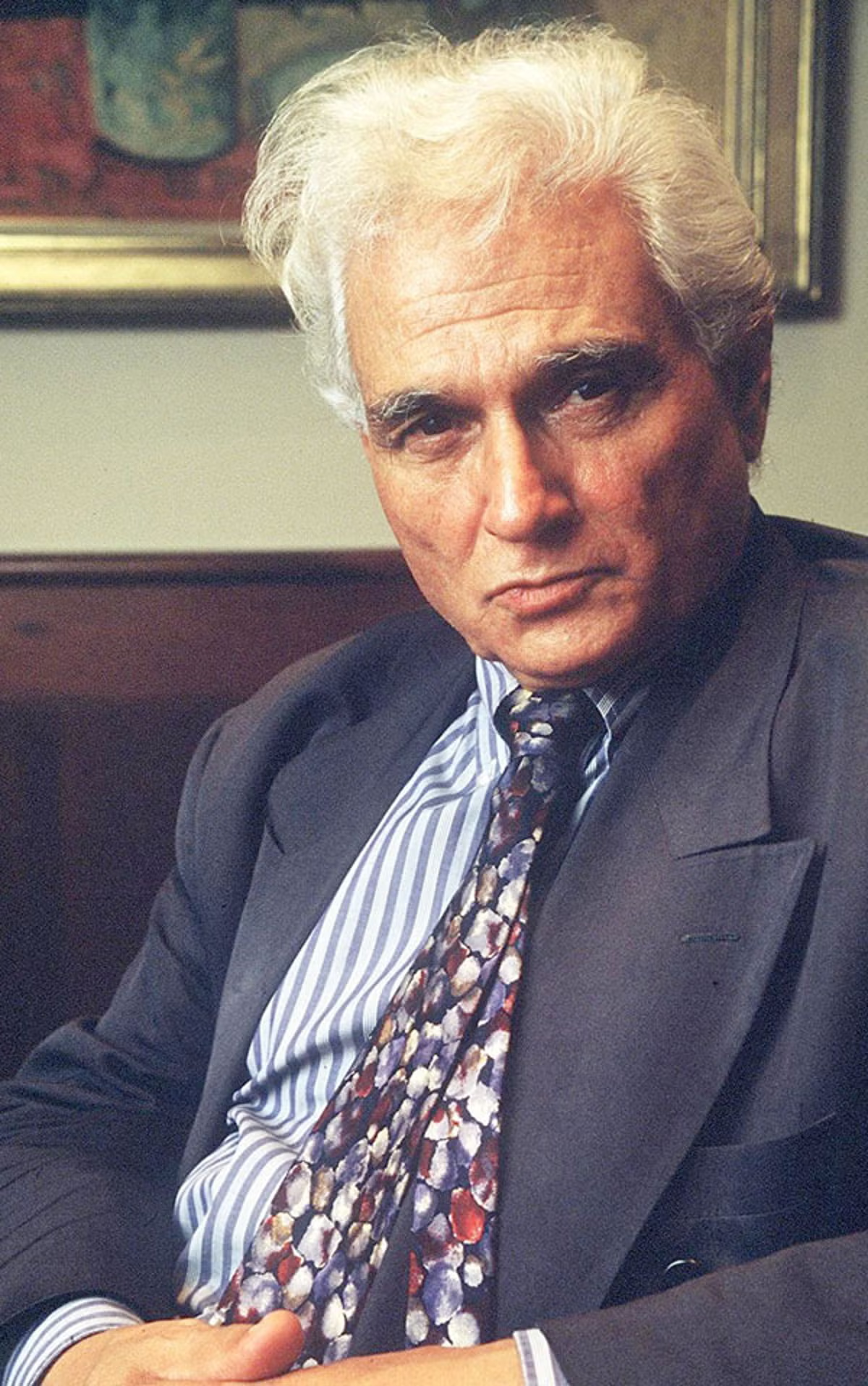

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004) is difficult. That is arguably what he is most famous for. Even his innovations in Deconstructionism and Poststructural linguistic theory are of secondary significance to the fact that his theories are difficult to understand. Indeed, the intellectual challenge of deciphering Derrida is part of his whole attraction to his acolytes; to his detractors however, his difficulty is all just unnecessary affectation. I sympathize with the latter, and do not dispute that his difficulty is at least partly affectation; however, I can also confirm from personal experience that his difficulty is at least partly unavoidable, because it is genuinely difficult to explain how all words are inherently slippery, using only words.

Difficult, but not impossible. Sometimes all it takes is a concrete illustrative example (something that not just Derrida, but most philosophers generally, give in frustratingly short supply). Take for example his characteristically-oblique line “The center is not the center” from his most influential essay “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” (1966). At first glance the line (understandably) comes off as infuriatingly circular, cloying, self-contradictory, and meaningless. There is, however, a practical and concrete logic to this line—namely, in the fact that the center is found in the peripheries. That may sound like a paradox, but it’s not. In fact, an illustrative example of the same can be found in Helaman 1:24 of the Book of Mormon, of all places:

“And, supposing that their greatest strength was in the center of the land, therefore he did march forth, giving them no time to assemble themselves together save it were in small bodies; and in this manner they did fall upon them and cut them down to the earth.”

The background context of this passage is that the Nephite dissenter Coriantumr has brazenly lead the Lamanite armies to invade the Nephite capital of Zarahemla, bypassing the outer cities entirely.

But this strategy swiftly proves to be short-term gain, long-term loss: the Nephite general Moronihah quickly encircles Coriantumr’s expeditionary forces, cuts them off from their supply-lines, and in short order forces their unconditional defeat and expulsion from Nephite territory. Coriantumr’s fatal flaw was that he assumed the center city of the Nephites was also the center of Nephite civilization—but, as Derrida might note with bemusement, the center is never the center, and Coriantumr’s inability to intuit that fact led him directly to military disaster.

Coriantumr is an interesting name in the Book of Mormon, because that is also the name of the sole survivor of the Jaredites at the end of Ether 15, who was discovered by the Mulekites in Zarahemla before their merger with the Nephites, after the utter collapse of the much more ancient Jaredite civilization. I only mention this because no less than Hugh Nibley, clear back in the 1950s’ The World of the Jaredites, has suggested that Coriantumr wasn’t the only Jaredite survivor to intermix with this ancient Israeli diasporic community. He conjectured that the Jaredites were of Asiatic extraction, based upon their Mongolian, Asian steppe-esque modes of total warfare[1]Something to bear in mind whenever we re-hash the debate of from whence come the Native Americans; those who point to the DNA evidence clearly affirming an overwhelmingly Asiatic origin ironically … Continue reading—that is, they are of a line completely separate from the comparatively-more-recent Israeli one. This is relevant to our brief discussion of Derrida, because he was an Algerian Jew—and if the modern Jews and these ancient exhilic Israelis share anything in common at all, it is a long-standing, implicit understanding that the center is not the center, as demonstrated by the midrash.

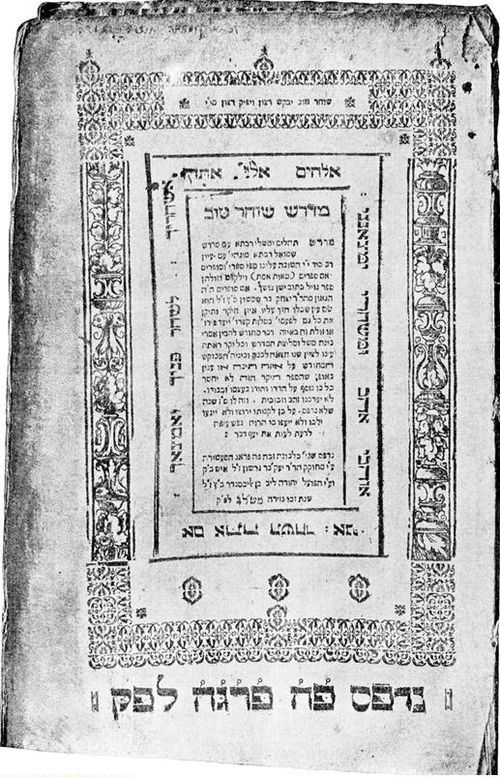

The midrash is a collection of Rabbinical commentary and exegesis that surrounds each verse of the Talmud (literally, as in the words wrap around the text on the physical page itself). That is, every Rabbinical scholar of the past 2,000-odd years has understood that “the center is not the center,” for the central meaning of the text is always found on the literal peripheries of the text. You do not just read the Talmud, but also the Midrash surrounding the Talmud, both of which are dependent on each other for their meaning, in an endlessly circular co-dependency. It is therefore not surprising that it took a Jewish scholar like Derrida to recognize that not just the Midrash, but all texts, everywhere, operate in a similarly slippery manner.

It is of course supremely anachronistic to posit that a Midrash tradition that only began to be written down in earnest after the 70 AD Roman destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem would have anything to do with an Israeli diaspora that disappeared overseas after the much earlier Babylonian destruction of Jerusalem in the sixth century BC. Nevertheless, we are still talking about a highly literate community in both cases; the Jews were obviously debating and commentating on their scriptures long before AD 70 (that’s certainly what Christ was doing in his own lifetime: engaging in constant verbal sparrings that the Pharisees and Sadducees, even at their most hostile, were always game for). Grant Hardy has argued in his recent Annotated Book of Mormon, the one put out by Oxford University Press, that the final part of 2 Nephi is a classic midrash on Isaiah—indicating the practice was already ancient long before Christ.[2]And again, third grade education farm boy Joseph Smith was supposed to understand the genre of midrash in 1829. Heck, the whole point of the Law of Moses was to point one’s own soul towards God, never towards the mere words themselves; even pre-exile, the center was never the center within the Mosaic Law. I suspect that, scripturally speaking, the House of Israel has long intuitively understood that the center is not the center.

I am of course in full speculation mode here, but what else is an essay for, but to jump and leap and make an attempt? Anyways, the Coriantumr of Helaman 1 does not appear to be directly descended from the House of Israel along any line; consequently, he did not possess this same intuitive sense that the center is not the center as the Israeli Nephites. Hence his frankly naive and foolish assault on the Nephite capital directly; it did not occur to him that the center is always on the peripheries.

So also is it with us, whenever we seek for the divine in the center, rather than in the peripheries, which per Derrida is the real center. The divine is not to be found in the mainstream of religion nor in the halls of power, privilege, or popularity, but in the margins of history, on the outside of discourse, where we are least likely to pay attention, even though it was there in plain sight all along. Or to quote another ancient Israeli text: “a great and strong wind rent the mountains, and brake in pieces the rocks before the LORD; but the LORD was not in the wind: and after the wind an earthquake; but the LORD was not in the earthquake: and after the earthquake a fire; but the LORD was not in the fire: and after the fire a still small voice.” That is, the spirit is not found in the sturm und drang of all the noise that saturates and surrounds us either, but in “the still small voice, which whispereth through and pierceth all things, and often times it maketh my bones to quake—”

References[+]

| ↑1 | Something to bear in mind whenever we re-hash the debate of from whence come the Native Americans; those who point to the DNA evidence clearly affirming an overwhelmingly Asiatic origin ironically agree with Nibley, the Book of Mormon’s staunchest apologist. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | And again, third grade education farm boy Joseph Smith was supposed to understand the genre of midrash in 1829. |