Abrasive was the word that cropped up in all the Steve Albini obituaries, and not without reason. This was the man, after all, who famously produced Nirvana‘s abrasive 1993 album In Utero–Kurt Cobain’s self-conscious attempt to get away from the high-sheen and gloss of Nevermind. Albini it was who cranked up the drums on the album to sound heavier, sharper, more expansive, more abrasive; even the guitars themselves sounded more percussive under his engineering.

Albini had had the practice: His first band Big Black didn’t even use a drummer—purportedly because he believed no human could keep up with his drum-machine, but also cause the electric guitars themselves became percussion instruments in his hands. Or was it that Albini was so abrasive in person, no drummer would work with him? He reportedly got himself banned from the only Punk-friendly venue in 1980s Chicago, due to how uncompromisingly abrasive he was (and that in a scene that prided itself on abrasiveness). Big Black’s 1985 debut Atomizer featured tracks about child abuse (“Jordan, Minnesota”) and setting yourself on fire out of sheer boredom (“Kerosene”). Their second album was called Songs About F***ing (asterisks not in the original). He used brazen slurs and profanity in his various song, album, and band names. He openly mocked many of the bands that entered his recording studio (including Nirvana themselves; called them “REM with a fuzzbox” and “an unremarkable example of the Seattle sound”). This was the Albini that Cobain wanted to produce In Utero; and when In Utero promptly became Cobain’s retroactive suicide note, Albini—anti-corporate, anti-mainstream, abrasive Steve Albini—ironically became the most sought after producer in ‘90s Alt-Rock.

But it’s important to emphasize here that he was never just abrasive for mere abrasiveness’ sake, but from a definite sense of moral outrage. The Village Voice in an early review of Atomizer noted that “Though they don’t want you to know it, these hateful little twerps are sensitive souls—they’re moved to make this godawful racket by the godawful pain of the world.” Albini notably refused to accept royalties for any of the innumerable albums he produced beyond the initial fee, saying his conscience wouldn’t let him do otherwise (given that In Utero alone sold over 15 million copies globally, that’s a lot of money he left on the table, but he by all accounts lost zero sleep over it). He called out by name the A&R men whom he saw screwing over his favorite bands in the ‘90s. He later pulled all his music off Spotify and promoted internet piracy, in protest of their raw deals against artists.

Likewise, though he did indeed use many slurs and profanities in early song titles and band names, Albini (to quote Pitchfork) nevertheless believed his real stances on race, gender, LGBTQ rights, and politics were obvious: “I have less respect for the man who bullies his girlfriend and calls her ‘Ms’”, he once said, “than a guy who treats women reasonably and respectfully and calls them ‘Yo! Bitch.’” (In this, Albini was reminiscent of Joseph Smith, Jr., who said, “I love that man better who swears a stream as long as my arm yet deals justice to his neighbors and mercifully deals his substance to the poor, than the long, smooth-faced hypocrite.”)

Then when Albini tweeted a series of apologies for his youthful slurs in 2021, it caught the whole world off-guard. But in retrospect, it shouldn’t have: as just noted, he used slurs not merely to provoke, but to highlight the linguistic hypocrisy of a society that places more importance on sounding good than on being good (something Christ Himself emphasized, you’ll recall). Then when Albini finally realized he was also being hypocritical, he confessed his sins and forsook them—that is, he repented, as we all must, but so rarely do. In even this, he was Punk Rock to the end.

This was the key difference between Albini and someone like, say, Johnny Rotten of The Sex Pistols, who—after decades of positing himself this loudly anti-Thatcher, pro-National-Healthcare Punk Rock provocateur—became a Trump supporter in 2016. But then, Rotten was only ever offensive out of a juvenile urge to be offensive for its own sake; his abrasiveness had no moral center (“Don’t know what I want/But I know how to get it” indeed). Rotten merely play-acted at hating bullies and oppressors, all while aspiring to be one; Albini by contrast, like Isaiah of old, really did despise the oppressor.

This has been a long, round about way to perhaps explain why it was that Albini—abrasive, offensive, world-famous Steve Albini—came to produce a pair albums for that most mild and Mormon of Indie-bands, Low.

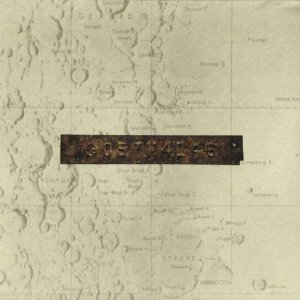

And not just any two albums, but the two most critically-acclaimed and fan-favorite albums of their so-called “slow-core” era: Secret Name (1999) and Things We Lost in the Fire (2001). Though Low would later go on to experiment with amplifiers, distortion pedals, and electronica, at this point in their careers they were still firmly entrenched in austere silences, glacial paces, and quiet volumes. Indie-sensibilities aside, Low at the turn on the millennium was about as far away from Atomizer and In Utero as possible. Theirs was music for freezing to death, not setting yourself on fire.

Moreover, Secret Name in particular is the most overtly LDS album in Low’s catalogue: The title of course refers to the Temple endowment ceremony and was recorded shortly after Alan and Mimi’s sealing; “Missouri” alludes to Adam and Eve in Adam-ondi-Ahman; “Two Step” seems to reference the Adamic language once used in the endowment; “Lion/Lamb” is an Isaiah/2 Nephi allusion, and “Weight of Water” mentions “the baptism of the earth.” (Heck, even “Don’t Understand” reads as a pretty understandable response to going through the Temple for the first time). Albini by contrast didn’t have a religious bone in his body, and these references either flew right over his head, or he frankly didn’t care.

And it’s tempting to say that Albini was simply taking the paycheck with Low, like he did with innumerable other bands of the era–many of whom, again, he openly mocked to their faces. This was a man as willing to work with Bush as with the Pixies (and he insulted both). He had also produced Bedhead’s final album Transaction de Novo the year before, so he was certainly no stranger to “slowcore” so-called, either.

But, again, Low worked with Albini not just once but twice–and each time to produce one of the most critically acclaimed and gorgeous LPs of Low’s career. Things We Lost In The Fire not only doubles down on the gentle beauty, but adds swelling strings for the first time. (“July” alone is worth the price of admission, and it’s not even the most heartbreaking song on the album). Whereas In Utero ended on a suicide note, Things We Lost ended on a new birth.

They never had a mean word to say of each other in the two decades since, and Albini had only kindness to say at Mimi Parker’s passing in 2022. Albini and Low by all appearances harbored genuine affection for each other, and had justified pride in their shared accomplishments. I don’t think it too far a stretch to say that Low perhaps had to start experimenting with amplifiers, distortion pedals, and electronica after Albini, because they had finally maxed out all the beauty they could possibly glean from their “slow-core” formula.

But then, I also don’t think it’s too far to say that Low, for all their own contrarian tendencies as well, had a strong moral center to their outrage as well (at least, so I once argued of their final two albums Double Negative and HEY WHAT). If they approached the actual act of musical expression from antithetical directions from Albini, they were both impelled by the same need to express their dissatisfaction with “the godawful pain of the world”, while simultaneously hunting for some beauty within that expression. This perhaps is what most drew them together, and made them fast friends when, by every other metric, they shouldn’t have been able to stand each other.