Without quite realizing it or ever consciously choosing to do so, I have become an aficionado of what I privately call Old Man Rock.

I don’t mean that pejoratively (I am fully aware, by the way, that Gen Zers nowadays like to ironically enjoy what they call “Divorced Dad Rock”–e.g. Nickelback and Creed–I am emphatically not talking about that); nor am I referring to Rock ‘n Rollers who just so happen to be old but otherwise try to act like they’re still 20-something (like The Rolling Stones); nor Rockers who merely sing of what it’s like to be middle-aged (like Bob Seger or Ben Folds or Double Fantasy-era John Lennon); nor even young Rockers play-acting at being old (like early Wilco or Dark Side of the Moon-era Pink Floyd). No, I’m referring to genuinely old men, ones rapidly approaching the end of their lifespan. Most importantly (and what distinguishes them from musicians who merely happen to be old), they use their age not just to look back on their lives, but to look forward and face the great and final mystery, the one Fact that we must all face, and should’ve been facing all along, yet spend so much of our lives actively avoiding instead.

Previous examples we have catalogued on this very site include:

-David Bowie’s Black Star, recorded while he was in the terminal stages of a cancer he kept so well hidden from the public that it genuinely shocked the world when he passed away in January of 2016–this, despite the fact that lyrically, the album entire is very obviously a eulogy for his impending death;

-Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker, released later that same year at the age of 82, just before his own passing, after he had already told the New York Times he was ready to die, and on which title-track he declared “I’m ready, my Lord”;

-Willie Nelson’s 2017 God’s Problem Child. The red-headed stranger of course isn’t dead yet, but seeing as how he was already 84 when the album was released, he made zero pretense to being any other age;

-John Cale’s MERCY, released just last year at the age of 80, and which finds the old Velvet Undergrounder seeking mercy at last, remembering his late-friend David Bowie, and telling the long-departed Nico that “I have come to make my peace”;

-For that matter, Low’s final album HEY WHAT also fits the bill, since it (like Bowie’s Black Star) was likewise written and recorded while a key member was battling a cancer they had kept carefully hidden from the public.

Again, what distinguishes these albums from the releases of artists who just happen to be old, is that they actually stare death in the face and confront the final mystery with eyes wide open, without pretense, sentimentality, or irony. For those of us essaying to be Latter-day Saints—wherein we are supposed to behave as though the end had already come, are scripturally commanded to “lay aside the things of this world, and seek for the things of a better”, and whose most sacred Temple ordinances prep us to pass through the veil and re-enter the presence of the Father—these sorts of albums should be of especial interest to us.

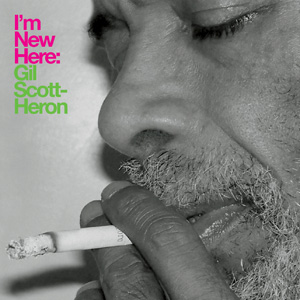

Indeed, I only recently realized (with some embarrassment) that there is a premier example of the genre that predates all these other examples: I’m New Here by Gil Scott-Heron, released in 2010, one year before his own passing at 62.

It had been his first new album since 1994—which in turn had been his first new album since 1982. Scott-Heron’s final decades had been heavily marred by drug addiction, rehab, and various prison stints on possession charges. It was an especially ignominious stretch for an artist who had roared out the gate at age 21 with his incendiary slam-poem “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”—a title that has long since ensconced itself into our pop-cultural lexicon, was a major influence on the development of Hip-Hop, and dramatically launched his own career as a politically-conscious Soul singer in the ‘70s. He deserved far better than what was done to him, and what he did to himself.

What is most fascinating about I’m New Here, in fact, is how much Scott-Heron, that most political of poets, dispenses with politics entirely on his final outing. Or, perhaps more precisely, he dispenses with overt politics; as the literary theorists have been at pains to remind us over the decades, the personal is always political, and Gil Scott-Heron here gets personal indeed. For example, the brief album is book-ended by “On Coming From a Broken Home” Parts 1 and 2, wherein he at long last opens up about how his grandma raised him as a child until “they sent a limousine from heaven to take her to God/if there is one.”

With the same didacticism he brought to his politics, Scott-Heron pushes back against the assumption that he came from a broken home (“what they called a broken home”), or that there must be something wrong with him cause “as every-ologist would certainly note/I had no strong male figure, right?” He righteously concludes the album by declaring, “My life has been guided by women/But because of them, I am a man/God bless you Mama, and thank you.” But again, the personal is political; for as Scott-Heron himself was doubtless keenly aware, the “broken home” rhetoric has oft been used as a dog-whistle to patronizingly pigeon-hole Black families as inherently broken themselves, as being permanently beyond repair or governmental intervention and therefore not worth the cost, as though centuries of slavery and segregation (both legal and de facto) and lynchings and police brutality and harsher prison sentences and red-lining and chronically underfunded school-districts and multi-generational poverty-traps and the entire white-power structure hadn’t a thing to do with breaking apart these families in the first place.

Yet though our nation’s miserable track record on race is certainly a subtext to “On Coming From a Broken Home,” it is, for perhaps the first time in his career, not the text. He opens by saying “I wanna make a special tribute,” and quickly establishes that he is here being entirely sincere: he really does just want to pay final tribute to the women who raised him, now that he’s so close to rejoining them.

Old age has sometimes been called “the second childhood,” which is a concept that Scott-Heron certainly seems to embrace on the title-track.

With a hoarse and raspy voice channeling every hard year of his age (this isn’t the affectation of, say, Tom Waits, in other words), he speak-sings, “No matter how far wrong you’ve gone/You can always turn around”–that is, we can always repent–as well as “Turn around, turn around, turn around/And you may come full circle/And be new here again.” That is, no matter how we get, we can still be born again, and become new like little children, for of such is the kingdom of God, and the course of the Lord is One Eternal Round.

These are emphatically not young man thoughts; these are the musings of a man preparing to shuffle off this mortal coil. If he is no longer opining on the political concerns of this current world, it is because he is already preparing for the concerns of the next. This is not at all to imply that Gil Scott-Heron had abandoned politics or given up or changed his mind on whether the revolution would be televised or not; only that he has already done all that he could in his brief mortal probation–after which it is by grace alone that he is saved–as are we all.

If the revolution never came about in his lifetime, he can at least still revolve himself, and “Turn around, turn around, turn around/And you may come full circle/And be new here again.” It is the one revolution that will for sure never be televised.

And if all our efforts to make this world a better place fail (“for all things must fail”), it is also the one revolution we can still make for ourselves. As the Lord Himself said to Moroni, “If they have not charity it mattereth not unto thee, thou hast been faithful; wherefore, thy garments shall be made clean. And because thou hast seen thy weakness thou shalt be made strong, even unto the sitting down in the place which I have prepared in the mansions of my Father.” If you can’t change the world, you can at least change yourself. Indeed, again, it’s the one revolution, if none other, that we should’ve been making all along.