In his influential 1919 essay “Hamlet and His Problems,” the poet TS Eliot provocatively argues that Shakespeare’s 1604 masterpiece Hamlet is an “artistic failure,” since the protagonist lacks what he calls an “objective correlative.” He compares Hamlet unfavorably to Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (the 1588 blockbuster that Hamlet‘s plot is based upon/ripped-off from), wherein the crown prince Hieronimo very obviously feigns madness in order to throw the Royal couple off his scent, and thereby better plan and enact his revenge. By contrast, Prince Hamlet never has a clear reason–an “objective correlative”–for any of the things he says or does, argues Eliot.

Certainly the famed “To be or not to be” soliloquy, quotable though it may be, does not move the plot forward in any discernible way; nor does his verbal sparring with Polonius, Claudius, or Rosencrantz & Guildenstern get him any better positioned to kill the King. Ultimately, Eliot concludes, Shakespeare must have bitten off more than he could chew with Hamlet, in trying to express something beyond his powers of expression, because little of the protagonist’s behavior throughout the play makes sense.

Of course, as innumerable literary critics since Eliot have noted (including CS Lewis, incidentally), the so-called “objective correlative” in Hamlet is painfully obvious: Prince Hamlet is grieving! His father recently died, his mother’s already remarried, and everyone’s already moving on with their lives. At every corner, Prince Hamlet has been denied the opportunity to finish the grieving process–and as anyone and everyone who has ever grieved knows, when you are still in the midst of processing your loss, you frankly don’t care about what anyone else thinks–or about anything else, for that matter. You become almost totally indifferent in your grief.

This has been a roundabout way of introducing Bedhead, the Texas-based Indie-band whom I mentioned in passing over a month ago in an essay on fellow “slow-core” pioneers Codeine and Low. Bedhead, too, was often classified with this genre tag (though they, like Codeine and Low, ultimately resisted and rejected the label as well). Yet whereas the influence of Codeine upon early Low is direct and obvious, Bedhead tends to only get lumped together with Low more generally, as similar byproducts of a larger, low-key reaction in Alt-Rock against the mainstreaming of Punk, Metal, and Grunge[1]which was really just a synthesis of the first two in the early ’90s.

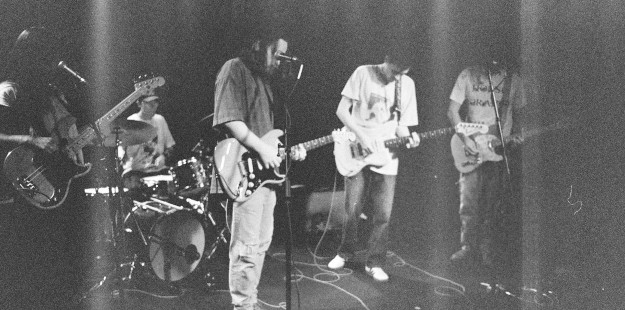

And indeed, although they were both quiet and melancholy, Low and Bedheads’ actual band set-ups were quite distinct from each other: Low was a trio playing intentionally austere arrangements that embraced the silences between notes, whereas Bedhead was a quintet featuring four(!) guitarists performing together in subtly-layered combinations; Low featured a husband-wife duo singing together in soaring angelic harmony, while Bedhead’s unassuming frontman barely sang above a whisper[2]Albeit this singing-style would become a definite influence on such 2000s Indie-icons as The Microphones and fellow Texan Ben Kweller; and of course Low’s expansive and critically-acclaimed career lasted all the way till 2022–when only death itself could stop the band in its tracks–while Bedhead quietly called it quits clear back in 1998, after only 6 years and 3 LPs together.

Yet whatever their larger musical differences, what Bedhead and Low definitely shared in common with each other[3]They also, incidentally, shared the fact that their most acclaimed album of the late-90s was produced by Steve Albini (1998’s Transaction de Novo and 1999’s Secret Name, respectively), … Continue reading is what they also share with Shakespeare’s Hamlet: an understanding of the importance of the grieving process. Bedhead was started by two brothers you see, Matt and Bubba Kadane, who formed the band shortly after their father died of a brain tumor. As Matt himself said in a recent interview just this year, their music was rooted in “an outpouring of grief… Bubba and I didn’t talk much about [their father’s death]. But we played music together”.

Certainly my interest in Bedhead became piqued once I learned that they had lost a parent to cancer while young (something that I, too, have tried to process in art before). Indeed, Bedhead’s abject disinterest in being even slightly more commercial to the mainstream–no riffs, no hooks, no distortion-pedals, no guitar-shredding, no sing-along anthems, no power-vocals, no drum heroics, no fashion statements, no music videos, no splashy album-art, no self-consciously poetic lyrics, etc., etc.–is the same Hamlet-esque disinterest in daily minutiae that the grieving manifest generally. Shoot, the sheer fact that their first two LPs were named the past-tense WhatFunLifeWas and the violent-death Beheaded, is also indicative of their preoccupation with end-of-life generally, as only the grieving can seriously consider.

Indeed, I wonder if part of why Matt and Bubba broke up the band in 1998–and promptly started another band tellingly-titled The New Year[4]Which featured Chris Brocaw, formerly of Codeine, on drums; for as much as these bands resented and rejected the “slow-core” label, they sure she seemed to be involved with each other.–is because they had finally completed the grieving process, and it was now time to do something else. Bedhead’s final studio album, after all, was named Transaction de Novo (literally, “a new transaction”), which Latin phrasing seems to suggest that it was finally time to start all over again[5]“Come Let Us Anew“, as we might also sing. Not for naught is the cover and title of their 2014 boxset Bedhead 1992-1998 reminiscent of a tombstone; they had finally finished burying their dead, and had moved on. As I’ve discussed before, it can be just as psychologically dangerous to never stop grieving (9/11-like) as it is to never begin grieving (Hamlet-like), so Bedhead was careful to quit before the grief became too artificial. Good for them! I mean that sincerely.

I have also argued before that Low, too, had a rather healthy relationship with the grieving process. As I wrote on the occasion of Mimi Parker’s passing just under a year ago, “It is here worth recalling that the title to their classic 1999 LP Secret Name is an oblique allusion to the LDS Temple Endowment ceremony, wherein the initiates are instructed in the series of covenants that will allow them to pass through the veil and re-enter the presence of God after death, and thereby continue their eternal progressions into the hereafter.

“Indeed, not just the Temple ceremony, but the funeral shroud placed over the sacramental emblems, the burial-and-resurrection imagery of the baptismal rite, our marriages of not ’till death do you part’ but for ‘time and all eternity,’ our vicarious ordinances for the dead, and even the white burial robes we wear during the endowment, all illustrate how our entire faith is imbricated in denying the final reality of death.” By constantly creating a place for the Holy Spirit in the empty spaces between their notes (as I have all-too-often argued), Low was invoking the peace of God which surpasseth understanding and those Pauline groanings beyond utterance–which Spirit comforts us not only in our daily trials, but in our profoundest griefs. If Bedhead and Low ultimately took different musical approaches towards processing their grief, they at least all intuited the sheer necessity of doing so in the first place.[6]Certainly such makes both Low and Bedhead oddly apropos listening for this Halloween/Day of the Dead season. But then, there is no single correct way to grieve.[7]Endnote: Although, as previously noted, pretty much every band that was grouped under the “slow-core” umbrella–Galaxie 500, Codeine, Bedhead, Low–ultimately disavowed the … Continue reading

References[+]

| ↑1 | which was really just a synthesis of the first two |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Albeit this singing-style would become a definite influence on such 2000s Indie-icons as The Microphones and fellow Texan Ben Kweller |

| ↑3 | They also, incidentally, shared the fact that their most acclaimed album of the late-90s was produced by Steve Albini (1998’s Transaction de Novo and 1999’s Secret Name, respectively), though that of course is nothing special; in the immediate aftermath of Nirvana In Utero, absolutely every Alt-Rocker was getting their album produced by Steve Albini. |

| ↑4 | Which featured Chris Brocaw, formerly of Codeine, on drums; for as much as these bands resented and rejected the “slow-core” label, they sure she seemed to be involved with each other. |

| ↑5 | “Come Let Us Anew“, as we might also sing |

| ↑6 | Certainly such makes both Low and Bedhead oddly apropos listening for this Halloween/Day of the Dead season. |

| ↑7 | Endnote: Although, as previously noted, pretty much every band that was grouped under the “slow-core” umbrella–Galaxie 500, Codeine, Bedhead, Low–ultimately disavowed the label, they nevertheless all shared one very hyper-specific detail in common: they all, at one point or another, covered a song by Joy Division. Specifically, Galaxie 500 covered “Ceremony,” Codeine covered “Atmosphere,” Low covered “Transmission,” and Bedhead covered “Disorder.” At first glance, Joy Division is a very peculiar influence for all of “slow-core” so-called to share in common, since they were (like all their post-punk peers) anything but slow. On the contrary, their high-speed freneticism was arguably their defining musical feature. But what Joy Division did have was a frontman struggling with mental health and suicidal ideation, who one day decided to beat death to the punch at the tender age of 23. Joy Division, too, was a band preternaturally preoccupied with death. Suddenly the through-thread connecting all these “slow-core” bands together–even when they weren’t being slow at all–comes sharply into focus. They all intuited the vital importance of befriending and reconciling with the great silence. |