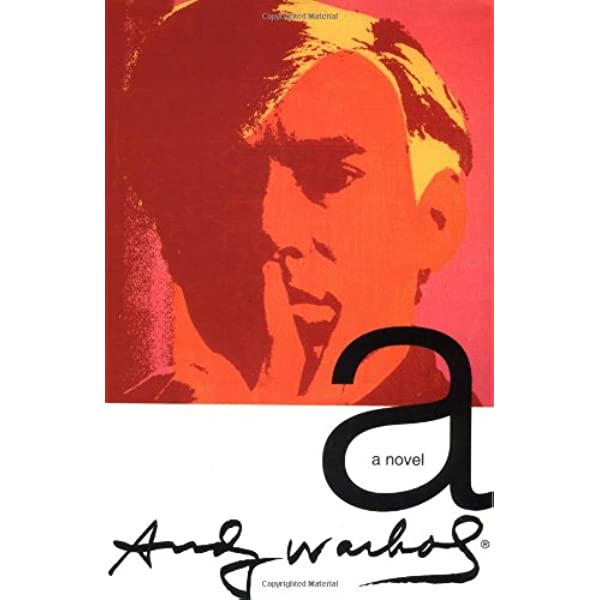

In 1965, Andy Warhol gave a tape-recorder to Odine–an actor, fixture at Warhol’s “Factory,” and dedicated amphetamine user–and asked him to carry it around recording his conversations over the course of a 24-hour period, in apparent homage to James Joyce’s Ulysses (another novel that famously offers a hyper-detailed record of a single day.) The resulting transcript, which included every single “ah,” “um,” “er”, and stutter that normally peppers a human conversation, was published in all of its polyvocal cacophony in 1968 as a, a novel.

At least, that’s how it was marketed: in reality, the recording took place sporadically over two years. At least four different transcribers were used, all of them amateurs, including Velvet Underground drummer Maureen Tucker (who, hilariously, refused to transcribe the swear-words, despite the fact that she was then in a band recording homages to Heroin and Sado-Masochism), and two high school girls who lost one of the cassette tapes when their mother overheard it and angrily threw it out. Purportedly Warhol, fully aware of how compromised the transcription had already become, leaned into the skid and made a few more random edits to the manuscript himself before sending it to the publisher.

It was vintage Warhol, to say the least.

The novel–or transcription, or art-project, or however you want to classify it–if it has any moral or lesson at all, appears to indicate the impossibility of recording every single moment with utmost fidelity. Even in our current surveillance state of 24/7 website updating, omnipresent camera-phones, police body-cams, insatiable social media posting and concurrent mass data-mining, and etc., the ability to record everything is fatally compromised by, say, camera filters, selective editing, odd-angles, corrupted files, or even just willful misinterpretations of what the raw video says (witness how many people still blamed George Floyd for getting strangled to death). That is, if a, a novel has a point (and that is still a debatable proposition), it is that there is no such thing as a perfect transcription of even a single day, no matter how thorough one tries to be. We are all separated by too many levels of mediation. As such, all records, even the most scrupulous ones, are inherently unreliable.

And it is here that I take a hard left pivot to recall how many times the Book of Mormon protests that it cannot contain even “a hundredth part” of the doings of these peoples. Indeed, the polyvocal writers of the Book of Mormon were keenly aware 1,600 years ago that a perfect record is impossible. To review: There is for example, in the opening chapters, Nephi’s 40-years-later retelling of early-life events, narrated with an apparent agenda of legitimizing his rule and separation from his older brothers after their exile following the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem; there are the repeated laments by the Book’s polyvocal speakers as to their own weakness and failures in writing (e.g. “Neither am I mighty in writing”, 2 Nephi 33:1; “for Lord thou hast made us mighty in word by faith, thou hast not made us mighty in writing”, Ether 12:23), which further undermines the Book of Mormon’s textual dependability; the inclusion of a much earlier Jaredite history dating back to the Tower of Babel “when the languages were confounded,” heavily abridged by a prophet-exile named Ether after the Jaredites’ self-destruction, recovered and translated by the Nephites into their own now-dead language, then further abridged, annotated, and inserted into the Book of Mormon record by Moroni after the Nephites’ own self-destruction.

And those are all the levels of unreliable mediation all just within the internal text itself; as for the book’s actual production, there is a barely literate Joseph Smith, Jr.’s purported translation of the same into an already archaic King James English mediated through seer stones in 1829; Oliver Cowdery’s and Emma Smith’s oral transcriptions of the same from behind a curtain, conducted without direct access to the plates; the loss and disappearance of the first 116 pages of transcription, never rewritten or recovered; publisher E.B. Grandin’s imperious punctuation additions to the galley proofs, which initially had neither chapter divisions nor punctuation marks; Smith still making sentence and grammar revisions to the text right up until the year of his death 15 years later; and etc. Like a, a novel, the Book of Mormon is saturated with multiple levels of unreliable narratives, damaged and flat-out missing source records, and radical epistemological instability in both transmission and source material.

Of course, neither Warhol nor Mormon appear to be particular interested in questions of fidelity; the words inevitably fail, for the simple reason that words are not the things they refer to. But that’s just another way of saying you need to look towards what doesn’t. It is what the words point towards that matters, not the words themselves. It is the Spirit outside the text that converts, not anything endemic to the text itself. Ironically, the multiples levels of mediation are what connect us together, not separate us apart.

Cause say what you want about the Book of Mormon’s radical textual instability: the opposite extreme, a, a novel, is no more reliable. Such may have been Warhol’s point after all. We must needs look for our assurances elsewhere—in the still small voice, and the peace of God which surpasses understanding.