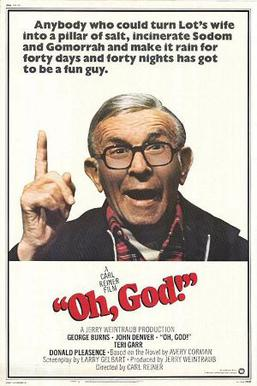

My brother is high-functioning on the autism spectrum, and so has highly eclectic tastes. Hence, last Christmas, he asked for a DVD of the 1977 comedy Oh, God!, solely because it co-starred John Denver. (Long story).

I dimly remember my family renting it on video cassette as a small child. The film stars George Burns as Yahweh himself (Burns himself was Jewish, natch), who quietly starts appearing to an unassuming young L.A. supermarket manager played by John Denver, calling him to be a modern-day Moses. Naturally, Denver’s name is soon “had for good and evil among all nations, kindreds, and tongues”, roundly mocked by the smart atheists and held “with great contempt” by professional theologians, who tell him “that there were no such things as visions or revelations in these days; that all such things had ceased with the apostles, and that there would never be any more of them.” You get the idea.

Things come to a head when a mega-church preacher whom God had instructed him to denounce as a “phony” sues John Denver’s character for slander. In the court-room climax, George Burns’ Almighty makes an appearance in human form as the defense’s sole witness (he speaks simply, “in plain humility, even as a man telleth another”), swearing on the Bible to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, “so help me Me.” With deft comedic timing, Burns’s God first does a cheap card trick to prove his divine bona fides, before then escalating to making the cards themselves disappear entirely before the Judge’s eyes–and then making his corporeal self vanish before everyone‘s eyes, as his disembodied voice announces to the stunned courtroom, “It can work. If you find it hard to believe in Me, maybe it will help to know that I believe in you.”

Not a bad line! Wish I’d written it myself. It recalls certain MTC dorm-room debates from days of yore, wherein we speculated if we must have faith to please God, is the corollary then that God has faith in us? The film ends with George Burns appearing to John Denver one final time, reassuring him that if all men “hold [him] in derision”, then he’s in good company; but God also then informs him that it is high-time he spend some time with his favorite animals in Australia, and so will not be coming back. Denver naturally asks what if he needs to talk with God again, to which George Burns responds, “I’ll tell you what: you talk. I’ll listen.” The final shot of the film is John Denver smiling as God vanishes.

By all accounts, the film was a well-reviewed box-office success at the time of its release, and resulted in at least two unremarkable sequels. I have not yet found any contemporaneous Church responses to the film; I don’t know whether the missionary department tried to capitalize on it as an example of a modern yearning for new revelation, or if anyone at Church HQ at least said “Hey, what the heck?!” when John Denver was cheered on for the very things Joseph Smith was loudly derided for. (If anyone knows of any Church commentary on the film, shoot us a line.)

What I would like to focus on now, however, over 45 years later, is just how vague God’s message is to his new prophet in Oh, God!. What, exactly, is it that George Burns has called John Denver to do here? Start a new Church? Restore the fullness of the gospel? Set up the United Order? Preach world peace? Simply get an increasingly secular world to believe God exists again? Or is it just to get us all to be nicer to each other? Likely by design, Burns’s message to his servant the prophet remains unclear.

I have mentioned before how Hollywood writers have on occasion gotten maddeningly close to the whole point of the Gospel–in Pixar’s Soul, in NBC’s The Good Place, in Jim Carrey’s Bruce Almighty–only to shy away at the last second; not because they feared that the apotheosis of the human race was too radical an idea for mainstream audiences, but simply because it honestly never seemed to occur to them.

Joseph Smith in the King Follet discourse declared: “Open your ears and hear, all ye ends of the earth, for I am going to prove it to you by the Bible, and to tell you the designs of God in relation to the human race, and why He interferes with the affairs of man”–and perhaps the strongest evidence for his prophet-hood (besides, you know, the quiet confirmation of the Holy Spirit) is in how he actually tried to explain why God interferes with the affairs of man. Specifically. In detail.

By contrast, it’s never clear what George Burns’s endgame here is with John Denver, largely because it’s unclear to any of us (least of all Hollywood screenwriters). Only Sci–Fi has gotten close. That’s because, as ever, it requires a revelation to realize it.