The Welsh iconoclastic John Cale has spent virtually his entire career better known for his influence than his music. Co-founder of The Velvet Underground (always listed second after Lou Reed–who pushed him out after their second album); producer for the debut records of The Stooges, Patti Smith, and Modern Lovers (acts who are also better known for their influence than their hits); and whose cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” launched a thousand American Idol entries. These are the stats that will stand attention at the foot of his obituary one day.

Which is a sincere shame, because his actual solo career has been astonishing: 1973’s Paris 1919 is just a perfect little piece of chamber-pop; 1975’s Fear is jam-packed with would-be/should-be avant-pop classics; 1982’s Music for a New Society (which was even quoted in The Watchmen) is a depressive masterpiece. In a more just world–“a stronger loving world“–these records would all be considered standards, essentials for any music-lovers’ collections; and the arrival of a new John Cale album for the first time in 11 years would be a much bigger event.

But then, John Cale was probably liberated to follow his muse wherever it flowed precisely because he never experienced, nor sought, genuine mainstream success. (Remember that Lou Reed kicked him out of the Velvets because Reed actually wanted to be popular; indeed, so much of the inconsistency in Reed’s solo output can be chalked up to the fact that he spent the rest of his life alternately courting and spitting in the eye of the mainstream, but in either case could never leave it alone.) He has no glory-days to either recapture or escape; in LDS terms, he has been freed from the vanities of this world to continue his Eternal Progression.

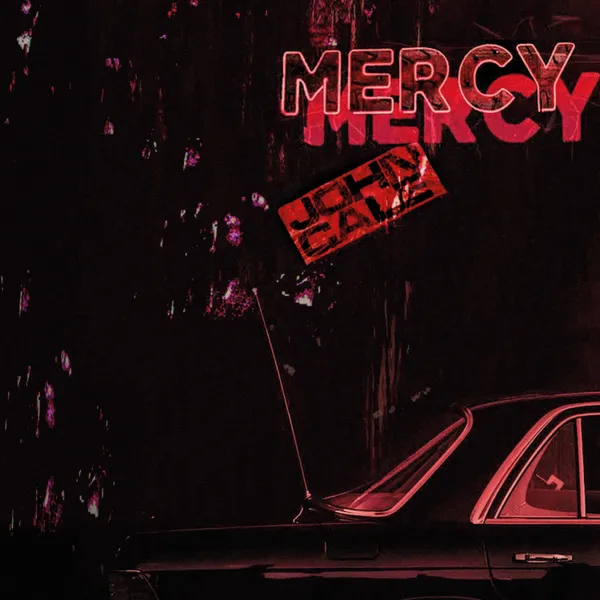

Indeed, his latest offering MERCY is an ice-cold R&B-influenced collage of electronic dreampop that features a host of collaborations with younger artists (my eyes very much perked up at the sight of Animal Collective) who were in turn long-range influenced by him. It is not only utterly unlike anything else he has ever produced before, but utterly unlike anything else being produced now, by anyone, in the Year of our Lord 2023. And he’s still doing this at age 80! His final approach to the veil has actually made him bolder, not timider.

This, of course, is rare. When Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, and the remaining Rolling Stones all finally kick the bucket, the world will mourn, but hardly anyone will be clamoring to hear their final release. They have all been coasting on auto-pilot since at least 1980. Even more recent acts from my generation–Pearl Jam, Foo Fighters, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jack Johnson, U2, Arcade Fire, Andrew Bird, Animal Collective, Jack White, Weezer, so on and so forth–have all largely settled into legacy status by now, releasing an endless series of competent but forgettable filler to pad out a Wikipedia entry and little else. Such is not unusual; not just our favorite bands, but most human beings generally, tend to calcify into settled opinions as we all grow old. There’s no avoiding it.

Or is there? David Bowie’s final album Blackstar, by way of contrast, was a bold new re-invention in a career replete with them. It was such an exciting new direction that it genuinely caught his fans off-guard when he died of cancer less than a week after its release. Bowie is especially worth noting here because 1) MERCY‘s lead-single and video “Night Crawling” centers on Cale’s 1970s friendship with Bowie; and 2) Bowie’s guitarist and collaborator from his ’70s hey-day, Mick Ronson, was LDS himself (his 1993 funeral was even held at an LDS London chapel). Whether these three men were all crossways influencing each other or simply all simpatico on the same wave-length, is less interesting to me than the fact that they all seemed to intuit the need for Eternal Progression–to never cease growing as an artist.

Or as a person, for that matter.

Take for example another stand-out track from MERCY, “MOONSTRUCK (Nico’s Song)“, his ballad for Nico, the Velvet Undergrounds’ one-time collaborator on their legendary 1967 debut. Nico had been placed in the band at the behest of their benefactor Andy Warhol, but was unceremoniously shown the door after just their first album (as Cale himself would be only one album later). “Please console me, yes please hold me/I have come to make my peace,” Cale declares to the long-dead singer–though to make his peace about what exactly, he doesn’t say. Had they ever been on the outs? Cale had helped co-write the songs for Nico’s solo debut Chelsea Girl post-Velvets, and had produced multiple of her other solo albums, including her final one in 1985, so it’s not like they had stopped being friends; nevertheless, something about how their professional relationship ended seems to have left a bad taste in Cale’s mouth. And though she’s been dead since 1988, Cale also apparently felt it was not too late to reconcile. I do not think it is out of line to read a sort of reconciliation and redemption occurring in this song–the album title is MERCY after all, and is something that an aging man preparing to soon meet his Maker would more likely than not have on his mind anyways.

I can already hear the immediate objection: this is John Cale we’re talking about here! A Velvet Undergrounder! A European art-rocker! There’s not a sincere religious bone in his body! Track 5 “Time Stands Still” literally opens with, “The grandeur that was Europe/Is sinking in the mud/The savagery that was the Church of God/Has already joined the club.” On track 7 “Everlasting Days” he also states clearly, “I’m not making excuses/I’m not making amends” (emphasis added); there’s no attempt at reconciliation here, one could argue, no atonement, no hope for Salvation–quite the opposite, in fact. “The Legal Status of Ice” for example is about Global Warming and how irredeemably screwed we all already are; and as Pitchfork astutely noted, each time he sings “It’s Not The End of the World” on track 9, “it feels more like a lie.”

But isn’t that all just another way of saying these songs are about how these are indeed the Latter-days? Do we not literally believe the same? (Not a rhetorical question; I witness the continued proliferation of MLMs and Ponzi schemes in our midst, and the growth of Church investment portfolios and financial holdings, and I wonder whether we really think the Second Coming is imminent at all, or believe that we really will stand before the judgment bar of Christ.) And it is here that I cannot help but note that the aforementioned track “Everlasting Days” finishes with Cale repeatedly “Thinking those days will be coming back”–as indeed they will, for “the course of the Lord is one eternal round.”

This is all speculation, of course, and I likely am just projecting myself a tad too much. No, what matters to me most right now–as I start to approach my inevitable middle-age–is that pioneers like Bowie, Cale, and select others have shown the way, on how to grow old gracefully, which you do not by trying to pathetically recapture the first flush of youth, nor by settling into a comfortable elderly recliner, but by continuing your Eternal Progression. But such an approach requires real faith that there really is something beyond this life that we are progressing towards. It requires one to not be endlessly preoccupied with the mainstream–or as our own scriptures phrase it, “seek not for the things of this world, but the things of a better.” In short, it requires a feeling of mercy–for others and for ourselves–and a belief in the very real possibility of reconciliation. Is such not the basis for our religion? And rather than debate whether John Cale actually believes these things, how about we ask if we ourselves do?

For these reasons and more, I have been immersing myself in John Cale’s latest album MERCY.