Abstract

Morton defines climate change as a wicked problem, meaning it has fuzzy boundaries, is defined by entangled multiplicities, is non-linear, unique, poorly understood, multivalent, and is not amenable to single or simple solutions (Morton, 2013). Wicked problems generate controversy because humans cannot grasp their temporal pace, dimensions, structure, nor how to influence their trajectories. French philosopher Gilles Deleuze offers terminology and concepts that may be useful in grasping, recognizing, and even taming wicked problems. Using techniques from Deleuzian literary analyses (see (Gilles Deleuze, 1986)), I will examine how the Book of Mormon serves as an apocalyptic text, depicting unaddressed wicked problems culminating in the collapse of societies, ecologies, and stabilizing structures of cultural maintenance. I will argue that the roots of climate change (e.g., poverty, income inequality, greed manifest as unrestrained consumption and war, and ecological inattention) are addressed in the Book of Mormon, arguing further that these roots are growing within wicked problems as described in that text.

In what follows I do an imaginative reading in which I draw on ecological Hebraist Ellen Davis’ (Davis, 2008) work on the pre-exilic writings of Jeremiah to set the stage for the ecological and societal conditions implicated in the collapse of Lehi’s Jerusalem. To better understand Lehi’s abandonment of his ‘land of inheritance,’ I will interrogate Deleuze’s notions of “deterritorialization,” “reterritorialization,” “Minor literature,” and “the fold” (G. Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). These terms should not be construed merely as Lehi’s family’s changes in location. Deleuze means something quite different. For example, deterritorialization refers to the way structures change in boundaries, content, and meaning. Using the term captures not only Lehites’ physical journey toward the promised land, but also his attempt to escape the economic structures, passions, and the embedded conditions of his cultural heritage that have precipitated a collapse of the spiritual ecology. Lehi’s family and associates fleeing the area are only a small part of their ‘line of flight’ and their move to deterritorialize their homeland’s cultural weight and influence on a covenantal relationship with God and the Land.

What I aim to show is that, rather than escaping those conditions, they carry a wicked problem into the promised land, which becomes the central problem in creating a society that does not recapitulate the embryological rhizome created by the cultural genetics of ‘Jerusalem’ (to use a biological metaphor). Deleuze uses assemblages and machinics (sic.) (a group of structures, objects, processes, ideas, etc. that instantiate an immanent, connected, and recognizable organismic-like whole) to explore how such deterritorializations and reterritorialization occur. For example, in his analysis of Kafka’s work, he shows how Kafka uses assemblages to visit reoccurring themes and concerns through various machines—in this case, various literary tropes and devices.

The Sword of Laban, is such a machinic device—and how its acquisition, replication, and persistence becomes a reterritorialization machine for recreating ‘Jerusalem’ throughout the sequence of events portrayed in the Book of Mormon—which ends in the apocalyptic dissolution of the Nephite civilization. Moreover, I will examine these finalities in light of current climate change and suggest that the Book of Mormon, under a Deleuzian creative reading, provides ways to think about the wicked problems confronting the Latter-day Saints during a time of climate change-induced ecological collapse. In particular, I will imagine how non-white bodies played a role in the collapse of the Nephite civilization which provides a simulacrum of our own civilization’s ecological and climatic demise through the use of hidden black and brown bodies in mineral and energy extraction. Note: This paper is a work of non-fiction, fiction, postcolonial studies, the exploitation of brown bodies, mineralogy, literary analysis, magical realism, philosophy, and science. In short, it is Deleuzian in both subject matter and in its construction.

Introduction

Yes, there’s a mine for silver

and a place where gold is refined.

Iron from the dust is taken

and from stone the copper to smelt

An end has man set to darkness,

and each limit he has probed,

the stone of deep gloom and death’s shadow.

He breaks under a stream without dwellers,

forgotten by any foot,

remote and devoid of men

The earth from which bread comes forth,

and beneath it a churning like fire.

The source of the sapphire, its stones,

and gold dust is there.

A path that the vulture knows not

The proud beasts have never trod on it.

nor the lion passed over it.

To the flintstone he set his hand,

upended mountains from their roots.

Through the rocks he hacked out channels,

and all precious things his eye has seen.

The wellsprings of rivers he blocked.

What was hidden he brought out to light.

Job 28:1-11 (Translation by Robert Alter)(Alter, 2019, 534-535)

Introduction

The Book of Mormon can be read as an apocalyptic text, as Christopher Blythe notes, “continuingly drawing on themes of destruction and renewal” (Blythe, 2020, 16) or as a typology of Eden (Austin, 2017, 13-16). In literary space, then, it spans from the beginning to end of Earth’s existence. These aspects make it relevant to unearthing parallels to the planetary, atmospheric, and apocalyptic ecological catastrophes unfolding due to anthropogenically driven climate change, causing our physical home to trip and lean into new energy-enriched trajectories staggering to and frow like a woman whisky-drunk and reeling. The Book of Mormon discloses many of the root causes of our current environmental crisis as the refugees and colonizers occupying the text become a simulacrum stamping out a short course on how to destroy worlds. This is not a pretty thousand-year history. It is filled with unseeing eyes, wars, greed, avarice, and the yearning of a people craving material wealth. A people who march to their annihilation with zeal. Cheering at the assembly of structures implicated in their own demise. Glorying in foolish mockery of its better and future angels. Not that there were no warning voices, as the scholar Rosalynde Welsh points out, the last prophet Mormon’s gives forewarnings that ought to have been heeded, “If they will not, the destruction of the Nephite and Jaredite peoples holds up a dark mirror to the future.” However, as the text illustrates, like us, they end up clutching at, and trying to maintain the unrelenting driving forces of their destruction. Likewise, even now, earth scientists—are, like prophets of old, raising a cry that a new geological era is emerging into the planet’s permanent stratigraphic layers that look like doom. Welcome to the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene is a proposed geological stratum that picks out the terrors that humans have afflicted on earth systems so thoroughly that they have enacted a signature change on the planet’s history. Arun Saldanha and Hanna Stark write (Saldanha & Stark, 2016):

“The Anthropocene is the geological age in which human impact on earth systems has become irreversible and will be detectable far into the future. It is therefore the greatest challenge currently facing life on earth. Its effects are omnipresent: ocean acidification, deforestation, the loss of species diversity through extinction, changes to the earth’s surface due to population migration and alterations to geomorphology, global warming and much more. Describing these changes as indicators of a new geological epoch acknowledges the unprecedented and planetary magnitude of human impact on the earth’s ecosystems and geochemistry.”

Climate change is considered a wicked problem. Meaning it has fuzzy boundaries, is defined by entangled multiplicities, is non-linear, unique, poorly understood, multivalent, and is not amenable to single or simple solutions (Morton, 2013). Wicked problems spawn controversy because the human mind cannot grasp their temporal pace, dimension, structure, nor how to influence its untamable trajectories. And it turns out that that which we cannot reduce to the fathomable packets of linguistic structures, we often declare non-exist. If it is not quantifiable, it does not exist. We are haters of wild emergence and material flows with a non-reductive nature. That which brings us to the edge of the sublime we find troubling and uncanny. That which we are unable to package to sell in parcels meted out as commodities do not exist. They cannot enter into our economies. Oil can be measured in barrels per day. We know how to pump it out of the ground, and what happens when we spray it into the air is not a concern. It is invisible. Why bother worrying about it?

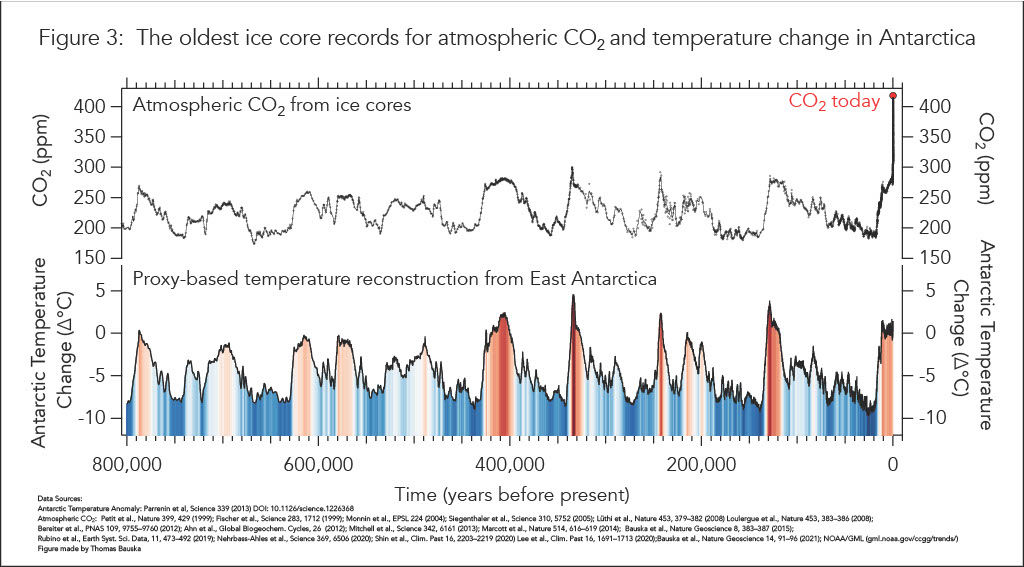

The climate of the earth varies. This we know. Sometimes significantly. This figure of temperature taken from the last 800,000 years is shown in (Fig. 1, top). We have a good sense of why it varies, which cozies pretty snuggly with the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (fig. 1, bottom). (citations within Fig. 1). Notice something. During the last 800,000 years, we have never seen Earth’s temperature, nor an increase in greenhouse gases, rise so rapidly or reach so high. As of this writing, the amount of carbon in the air is approximately 411 ppm, over a hundred parts per million more than the highest peak seen in the ice core data.

The earth has been much hotter in the past, even hotter than we see in the record presented in fig. 1 of the past 800,000 years. During the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum about 55.5 million years ago, the earth was 5-8o C hotter than it is now. The icecaps melted. Rainforests covered the poles. The equatorial regions, where we now have lush rainforests, were deserts. This was created by 50,000 years of carbon dioxide release of approximately 0.24 Gigatons per year. In 2019, 36.8 gigatons of carbon were released by humans. There is a consensus by thousands of scientists who study the climate, that earth is changing at an unprecedented rate because of the release of carbon into the atmosphere by humans, largely through the burning of fossil fuels along with exacerbating forest emollition due to widespread warming-induced droughts and associated wildfires. If you believe in any sense that science contributes to knowledge, climate change is an undisputed scientific fact. To argue otherwise is to misunderstand science. There are many excellent resources for understanding the science behind climate change, so I will not present that story here but it is well-documented, and only disputed by thinktanks funded by oil companies (Oreskes & Conway, 2010)

To explore the Book of Mormon’s apocalypses and the concerns of climate change today, we will need to wander a dark path. The following fabulation stretches from Nephi’s lust for gold and his people’s use of non-white bodies for the extraction of ore to our own exploitation of the poor, also largely non-white, to satisfy our use of fossil fuels and metal-rich ores. I will draw on insights from French philosopher Gilles Deleuze to develop concepts useful for exploring the parallels between the Nephite record and our current slouch toward a modern apocalypse with similar causes and commitments. As Saldanha and Hanna Stark continue,

Climate change therefore presents a dispersed and enduring problem of such scale that it becomes, according to Timothy Clark (2015), unreadable. Timothy Morton (2013) calls it a primary example of a hyperobject’, an assembling of elements so complex and distributed that it challenges the post Kantian definition of ‘object’. However, this insistence on ineffability and opacity restrains the thinking necessary to confront the disastrous earth scenarios that are being predicted for the twenty-first century. Global human society has arrived at a pivotal moment in the production of scientific, political and philosophical subjectivity. The urgency and opportunity of engaging with the Anthropocene is clear in the unprecedented pace at which public, political and philosophical debates about climate change are developing and intensifying.

Deleuzian Preliminaries for This Reading of the Book of Mormon

As we face a human-caused planetary catastrophe, at least as far as our human culture is concerned, what can be done? Can the Book of Mormon help? Deleuze births terminology and nurses (in the lactative sense of nourishing) concepts that may be (re)productive in grasping, recognizing, and even taming wicked problems. Midwifing Deleuzian literary analyses (for further information see (G. Deleuze & Guattari, 1986) provides a style of engagement that draws on new systems for approaching a text. For a Deleuzian analysis, we need the skills of a tarot reader rather than a stenographer. Rather than going deeper into the text, we must move up higher into the warming atmosphere to capture a satellite image of the landscape. As James Faulconer suggests, occasionally, we need to move to a higher spot to get a sense of the theological aspects of the landscape, “For us, too, that high spot won’t give us the details of what we are looking at. We will miss a great deal. . . . The overlook will allow us to make general points that help us compare things . . . and that might lead us to ask questions about them that we might otherwise not think of’ (Faulconer, 2020, 14).

And from that lofty perspective, we must take for our concepts the bold color strokes of a van Goethe or a Matisse painting and draw outside the lines and make bold conjectures of color and form. In short, we need a storyteller’s fabulations rather than the cool reductive analytics of the logician.

Where most of the major branches of philosophy are afflicted with getting something right or disclosing the truth, the French philosopher was concerned with doing something novel, creative, and playful; in capturing new concepts, he often claimed that asking whether some particular is true was the wrong approach to philosophy (or the study of religion or literature or life). In his interviews with Clair Parnett, Deleuze made clear his disdain for most schools of philosophy, largely because they focused on either language or perception while missing important aspects of imagination and novelty. Art, literature, and, yes, science were the canvases from which he created his philosophical concepts. Because I am taking Deleuze seriously, the style of this essay does not fit easily into either a typical academic essay, research article, or fiction, although it partakes of all three in the form of midrash, speculation, playfulness, science, and other nonstandard textual experiments and innovations. I hope the reader will be indulgent in recognizing that there is no such notion of getting Deleuze ‘right.’ He encouraged and modeled fancy and play. Even Deleuze did not often get Deleuze right.

Gregory Flaxman describes this as a species of fabulation, “Deleuze affirms the powers of fiction to outstrip our most calcified opinions and encrusted habits of thought. To write is to fabulate new modes of existence that carry us “of the rails’.” p. 4. This is the aim of this paper. So the right question is, not did we get things right, it is, was our exploration creative, novel, and what work does it do to capture novel concepts? To be creatively productive.

Flaxman calls this work sci-phi (a play on sci-fi, code for science fiction). He argues that Deleuze defies representation (Flaxman, 2012, 318),

“To the degree that Deleuze is represented, he is always misrepresented because we have failed to appreciate the expressive dimension of his philosophy that in thinking and writing, goes beyond philosophy

. . .

We have posed sci-phi not as the solutions to his problem so much as its means of expression, the imagination of all kinds of alternative realities at once utopian and disarming, uncanny and familiar, scientific and fictional.”

Deleuze, therefore, makes an appropriate traveling companion for this exercise in waltzing with the Book of Mormon because he saw philosophy as an art—an act of creation. Ideas were couched in terms of how productive they were in bringing novelty into the world, in creating concepts that make one think differently. Gregory Flaxman shows how Deleuze, drawing on the work of Nietzsche, uses fabulation to reorient thought to move beyond critiques based on exploring the true and false and create a new “style” of discourse that opens new territories of engaging with the world.

The Book of Mormon lends itself in particular to this kind of thought-experimental undertaking because, whereas problems of the historical, the hermeneutical, and exegetical have dominated the discourse within the Mormon tradition, Deleuze offers novel ways of playing with concepts and new modes of expression that are amenable to examining new questions and new relevancies discovered through more creative readings not tied to modern and post-modern and post(n+1)-modern critiques and analyses. It is experimental. As Tod May explains,

“To experiment is not necessarily to succeed. But it is also not to walk away from what is there. A line of fight is not a flight from reality, but a flight within it. It does not create from nothing but rather experiments with a difference that is immanent to our world. There is always something more, more than we can know, more than we can perceive. The question before us, and it is a question of living, is whether we are willing to explore it, or instead are content to rest upon its surface.” (May, 2005, 170)

The Book of Mormon, if it is to be useful for our day, is to explore the question of how might one live? Not a normative question of how we should live? But how might we live? What new things might we create in our lives, societies, and civilizations? And in light of the ecological catastrophes we see surging into the world the question takes on fresh valiance.

Book of Mormon as Minor Literature

To explore how we might gain a more theological perspective on the question of how to live, we need to explore how the Book of Mormon might be viewed in novel ways. We will first think about what Deleuze means by “minor” literature. By minor or minority literature, Deleuze does not simply mean literature written by minitories (although that is often the case). Its roots lie in his and Felix Guattari’s work on Kafka. For example, Deleuze considers minor literature works such as Melville’s Moby Dick and Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Minor literature has three aspects, “The three characteristics of minor literature are the deterritorialization of language, the connection of the individual to a political immediacy, and the collective assemblage of enunciation. We might also say that minor no longer designates specific literatures but the revolutionary conditions for every literature within the heart of what is called great literature” (Deleuze, 1986, 18). Alternatively, as Flaxman interprets and retranslates the quote above, “First, in minor literatures, language is effected with a high coefficient of deterritorialization, [which I explain further below]; second, ‘everything in them is political;’ third, in minor literatures ‘everything takes on a collective value’” (Flaxman, 2012) p. 207. Can it be argued that the Book of Mormon does not deterritorialize both Christianity and the American religious milieu? Or does not the book allow the emergence of a new politics of meaning? Or do we not find the collective value of people’s orientation toward the book demands a new set of normative stances? While I do not elaborate, there is a compelling story to be told of the Book of Mormon’s emergence (and I mean that in the formal sense of complexity theory, i.e., the study of emergent patterns that flower into the world from the interaction of multiplies in time and space) into the world through Joseph Smith.

One often neglected character in the Book of Mormon is God. Of course, he infuses the story. He hovers over the face of the story as a ubiquitous presence much like the oceanic water in Moby Dick is mentioned upwards of 250 times, but its properties are rarely mentioned, but it is often adjectively, especially visually, described. Nor would the properties of oceanic water need mentioning because Melville’s readers presumably know them well. Similarly, God forms part of the “paratext” of the Book of Mormon. Borrowing from R. John Williams, a paratext is nicely described, “In the field of literary narratology these efforts might be characterized as attempts to separate the text of The Book of Mormon from its “paratext.” Defined by literary theorist Gérard Genette, a text’s paratext consists of all the material and cultural elements at the “scene” of reading that surround or otherwise package one’s encounter with a given text, including all those “liminal devices and conventions, both within and outside the book, that form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher, and reader” (Williams, 2020). There is much theological richness in the Book of Mormon but it must be derived, extracted from hints, argued, nuanced, inferred, debated, put forth, suggested, elaborated, and in short, pried from the text. And in the productive spirit of Deleuzian fabulation, mined for novel, imaginative insights and the construction of useful concepts.

Three Deleuzian concepts

Let’s begin by playing with the Book of Mormon using three Deleuzian concepts. The first is that of machinic assemblages. In particular, we will look at a specific kind of autopoietic system, that is, systems that emerge into the world and self-generate and self-perpetuate. Life is an example. So is the Postal Service. As we will explore momentarily, we will find this kind of machinic assemblage in the conditions of Jeremiah’s Jerusalem as the Book of Mormon opens, and under inspiration from God, Lehi flees into the desert. We will see that this particular machine remains in force not only in the Book of Mormon, but in the world we find ourselves living in today.

Machines

The Jerusalem-machine can be identified as all of the flows that maintain Jerusalem as Jerusalem, including its people, the movement of the matter and energy that flows in and out. This includes trade routes; flows of crops, metals, livestock, and slaves. It includes historically contingent ways of doing things, relationships, parleys between people exchanging goods in local markets, and negotiation between nation-states. It includes war machines, mining metals, the exchange of capital, the suppression of some people and exaltation of others. It includes art and rituals. It includes political ties and breaking ties from places both near and far. It consists of the knowledge and history of a thousand different parts in motion, from how to make and manufacture pottery, to crafting leather straps and saddles for camels, producing ropes, cloth, and blankets both within Jerusalem, or brought from other places. As we will discuss later, this includes mines for gold, silver, tin, and copper, which connect it with the slave markets of captured peoples. Mining, refining metals, and shaping and working metals into useful implements will concern us much here. The complex Jerusalem-machine creates ways of doing things. As described by cybernetic system dynamics (Humphreys, 2016; Kauffman & Kauffman, 1993; Luhmann & Gilgen, 2012), the Jerusalem-machine emerges into the world as an autopoietic system that maintains its structure and self-existence in ways that allow it to be put on a map, pointed to, leave from and arrive at. This means that there is more than just matter in exchanges with other matter; there emerge things that never existed in the world that are novel and bubble up through the edges of all this commotion. The machine that emerged in the desert as a historical, evolutionary, societal, and very contingent entity exists in the world as a stable flow of energy and matter coalescing and moving in specific recognizable patterns. However, this pattern can indeed create novelty. For Deleuze, such machines emerge at different scales, are composed of other machines, and create larger systems of assemblages and machines. I will focus on the Jerusalem-machine in what follows, but do not forget that there is also a machine, for example, that works to keep rats out of the grain being transported by merchants that are a part of the Jerusalem-machine. Keep in mind that often these kinds of machines can take off in directions that drive conditions that no one chooses or wants. The machines become like Darwinian primitives that move toward their own goals, courses, and in unexpected directions that no one wants or can control. As Deleuze writes (Deleuze, 1993, 106), “However difficult it may be, we must think of the naval battle beginning with a potential that exceeds the souls that direct it and the bodies that execute it.” We see them in our day and will become relevant in the Book of Mormon and in driving the Anthropocene forward. We see this in our day, as a demon narrator describes the conditions driving the Anthropocene forward—blind, relentless machines of corporate power, devouring the world, as described in my novel, The Tragedy of King Leere, Goatherd of the La Sals:

They are Darwinian primitives. Great corporate amoeba that role along in a quest to obtain more resources of money and power. They worship no gods. They practice no morals. They are unstoppable once they have reached a certain point of existence. They will attract the people they need to play the roles they demand in order to march toward their telos—which is always, always more. And they will devour their own resource base like bacteria in a jar that consumes all until their environment is poisoned, the food base depleted, and there is only one left to bear witness to the fate of its fellows before it too perishes. Even now they gather wealth, and like any energy driven system spew forth heat. Heat that will eventually cook the world. The Archons have arisen on earth. Alas for poor humans. (Peck, 2019, 83)

They roll through the world without regard to the humans that have created them. The archons of our day are an instantiation of a concept similar to the Jerusalem-machine of Lehi’s day. It would also seem, by Jeramiah’s writings, that God hates the way this machine has unfolded in the world. We will look closely at this momentarily.

Deterritorialization

The second Deleuzian concept we explore is that of deterritorialization—creating a line of flight that removes us from one set of machinic assemblages to another. In the opening scenes of the Book of Mormon, we find the Lord attempting to deterritorialize Lehi and his family from the Jerusalem-machine. To look at Deleuze’s idea of deterritorialization, ants will be useful (as Proverbs recommends) much as Deleuze used bits of science, literature, and philosophy to explore his thought.

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) is highly territorial. These ants eat almost anything and where they have established a nest few other animals survive. They can kill large mammals, other insects, and, if they do not fly away, birds. Their nests are enormous, and unlike most ant species, their plutonic tunnels support multiple queens, increasing the size of their territories to the order of hectors rather than meters. A colony of S. invicta patrols its nest’s territory thoroughly and restlessly, always in search of invaders or intruders or just unlucky wanderers that stumble into the wrong place. Even so, there is an ant that lives among them, invisible. The ghostlike ant species, Pheidole dentata, is an uncanny species unremarkable enough to not even have a common name outside of its scientific appellation. It manages to nest hidden in the midst of one of the world’s most dangerous ant’s relentless vigilance. All ants, when encountering another insect species, will attack and kill it. If there seem to be too many other ants, they will use pheromones to recruit others to help destroy the other invading ants. P. dentata does this as well. Like most species, they have a sense of what makes a proportional response in attacking invaders. Evolution as tutored them that they should not recruit more ants than they need, lest resources are wasted. P. dentata survives by doing something special when they encounter a fire ant patrol, be a single ant or several. They have a special pheromone that means “fire ant,” and when it is released, the nest recruits everyone available in the nest to attack. They come out en masse. They scour the area of fire ants. When they discover one fire ant, they fill the air with a particular scent that signals other nestmates to attack. And this they do fiercely. For several minutes after the fire ant signal, they remain agitated, extra vigilant, searching the nest area for other fire ants. Thereby their colony remains undisclosed to fire ants. The Solenopsis space is breached. The fire ant’s territory is deterritorialized, in the sense that it has become changed, it has become something new and different than it was when its boundaries were secure. The heart of deterritorialization is its going from a form of temporary situated-being to a state of becoming something different. Novel. Other than it was. It could be reterritorialized and often is should they find the P. dentata nest, which they immediately destroy. The agent, or as Deleuze, might call it the machine or mechinc forces, of the change in this particular S. invicta territory, is the arrival and modification of their place by this wily other species able to live quite contentedly in this formally unhospitable region.

One more thing needs to be drawn out here. In common parlance, and in language any myrmecologist worth her forceps would agree, the territory of both S. invicta and P. dentata would refer to the physical boundaries of the colony’s area of concern. However, while Deleuze and Guattari mean that too, they also mean something richer. The territory would include not just the spatial extent that the ants defended but all of the matter and associated processes recruited to establish and maintain the presence and persistence of the colonies. It includes evolutionary forces at work. The ecological relationships that connect the ants with the biotic and abiotic world around them. This might include their neuroarchitecture, the plants on which they feed, the shade that affects their ability to orient using the sun, the parasites and predators that affect the success of the colony, rainstorms that increase or decrease the effectiveness of their pheromone communication systems, in short all those things at go into the geopolitics of an ant territory. A territory is a machinic assemblage. Thus, when I speak of a Deleuzian concept, territorialization or deterritorialization in what follows, I am evoking more than might be readily brought to mind by spatial relationships and boundaries, or even can possibly be brought to mind. It is more than just leaving a territory. It is often being repositioned vis-à-vis a new machinic-assemblage.

The Fold

The third and last Deleuzian concept we use is that of the fold. This was developed through his work on Baroque art in the 18th century and Leibnitz’s monadology. This is more complex than I will describe here, but Deleuze was concerned about how complexity can be folded from an outside to inside, to an interiority that holds and preserves the outside. This can happen in matter, symbol, or in other modes of being. McDonnell captures Deleuze’s thinking on the fold nicely (McDonnell, 2010), “The material force of resistance to movement is conceived as a foldings or envelopment of an outside, whereby an inside is constituted through its imitation. The capacity to be affected is a spontaneity to the outside directed toward the state of things from change follows’. This folding of the outside on the inside substantiates the difference in depth or the power of parts to repeat.” Deleuze points out that it holds for biology, political economy, and linguistics (G. Deleuze & Hand, 1988, 128). Speaking of his friend Foucault (Ibid., 97), “. . . dimensions of finitude which hold the outside and constitute a ‘depth’, and ‘density withdrawn into itself, and inside to life, labor and language, in which man is embedded. . .The inside as an operation of the outside; in all his work Foucault seems haunted by this theme of an inside which is merely the fold of the outside, as if the ship were a folding of the sea.” He also draws on science to illustrate the idea, “Folds of winds, of waters, of fire and earth, and subterranean folds of veins of ore in a mine. In a system of complex interactions, the solid pleats of “natural geography” refer to the effect first of fire, and then the waters and winds of the earth; and veins of metal in mines resemble the curves of conical forms, sometimes ending in a circle or an ellipse, sometimes stretching into a hyperbola or a parabola. The model for the sciences of matter is the “origami,” as the Japanese philosopher might say, or the art of folding paper.” (Deleuze, 1993, 6). Perhaps the simplest example I can describe is the folded up nucleic acid of DNA, which has incrusted in its crystal folds the attributes of the organism from which it is derived, that in an appropriate environment will recreate a new instantiation of that organism. What is clear, is that for DNA to unfold a new organism into the world, it takes a load of cellular machinery to persuade its recreation from its precursors. We will use this concept to follow how the Jerusalem-machine follows Lehi into the New World.

We are now ready to turn to the Book of Mormon. Deleuze argued the task of philosophy was to create concepts, “…philosophy is the art of forming, inventing, and fabricating concepts” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, 2). These concepts are developed in what he called the Plane of Immanence, by which he meant the conditions, flows, processes, critiques, and frameworks under which concepts are developed. The concepts I will develop in this essay include the archons or the “Jerusalem-Machine.” This is the concept of emergent material structures flow from the behavior and interests of Homo economicus under certain conditions of human behavior in relationship and systems theory marking machinic forces folding and seeding complex systems (Persky, 1995). The Plane of Immanence that conditions these concepts will be developed vis-à-vis the Anthropocene is the use of black and brown bodies in the extraction industry for mineral and carbon resources. We will explore how non-white bodies are converted into gold, silver, and precious metals. Or today in the bodies used in the extraction of coal, oil, the use of which is warming our planet. To rare earth metals such as thulium, lutetium, and other metals used in all of our electronic computer-based devices, the extraction of which creates multiple ecological disasters. Ore extraction of metals is one of the most labor-intensive actives found in the ancient world. As it is now. And since the rise of civilization it has been extracted largely by invisible bodies by the poorest of the poor. In addition, these technologies are implicated in the widespread exploitation of labor. What follows is a Deleuzian Sci-Phi story about the Nephite apocalypse that serves as a warning for what we might be facing. I am not doing apologetics per se, except in the sense that it has always been done by creating fabrications. Rather than tying my fabulations to tie to a archeological reality or history, my aim is to see how the Book of Mormon might demand examination of how we treat the poor to undergird our privilege and how by not attending to those bodies that make our lifestyle possible, we are ripening for apocalyptic endings.

[Part 2 will conclude this essay next Tuesday, August 9.]