It has long been a source of bemusement for NBA fans that the league team for Salt Lake City is called the Jazz. Originally an expansion team for New Orleans (where the moniker “Jazz” naturally made a lot more sense), the franchise’s abrupt move to Utah in 1979 has never stopped sounding hilariously, self-evidently incongruent, like Jumbo Shrimp or Military Intelligence. Not even the team’s rise to playoff supremacy during the Carl Malone/John Stockton years could quite erase the inherent joke of “Utah Jazz.”

The sources of that bemusement are not hard to trace: New Orleans of course is the birthplace of Louis Armstrong, Dixieland, and a large Black population who developed Jazz as a way to both escape and express their profound melancholy as the children of former slaves still oppressed deep in the heart of the Jim Crow South. Salt Lake City, by contrast, is the headquarters for the LDS Church, which had only ended its ban on Black Priesthood ordination the year before the Jazz arrived. Certain early Mormon pioneers even brought over Black slaves of their own to Utah territory, and the state remained largely hostile to the Civil Rights movement throughout the majority of the 20th century (see for example James Weldon Johnson’s scathing 1933 essay “Outcasts in Salt Lake City“, or Ezra Taft Benson claiming that Martin Luther King, Jr. was a communist agitator in his 1969 John Bircher polemic An Enemy Hath Done This).

Nor is all this racial prejudice yet in the rearview mirror: A Utah fan used racial slurs against Russell Westbrook as recently as 2019 (albeit resulting in a life-time ban), and Davis County school district was cited by the DOJ for “widespread racism” as recently as 2021. Remember that the whole fracas with Brad Wilcox reciting racist folk-doctrines at an Alpine youth fireside was only this past February. Jazz music was made neither by nor for the people of Utah.

But that’s not to say it couldn’t be. President Nelson has lately paired with the NAACP in denouncing racism, and more importantly, the continent of Africa is currently where the Church is experiencing the most growth. But it’s not just shifting demographics that may one day make “Utah Jazz” a little less of an oxymoron: it’s in the very nature of our epistemology itself, the way in which we claim to understand the Holy Spirit.

By way of comparison, this very site has leaned a little hard on Low (as you may have noticed), but the same things that have been said about the innate spirituality of Low’s music–“their fearlessness in embracing the silences between notes, [which] allows them to create a space for the very things that can’t be said, that can’t be represented, the ‘unspeakable’ thing outside discourse”–applies at least as much, if not more so, to Jazz, wherein “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don’t play.” (As many a wise-acre has also said about the Utah Jazz, “It’s not about the championships you win….”)

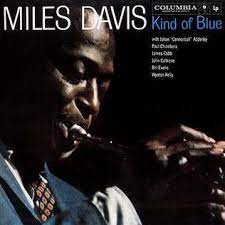

Of course, in fairness, that latter quote comes from Miles Davis, who is a rather singular figure in Jazz. In contrast to so many of his contemporaries during the hey-day of 1950s BeBop, Davis distinguished himself by looking for notes to cut, not to add. He could play as complexly as anyone (see for example his 1958 LP Milestones), but also said the music was getting “thick,” and the melody lost. Hence, while everyone else was in an arms race to see who could cram in the most scale-runs, the most flourishes, and the most chord-changes into their solos by the end of the ’50s (with Ornettle Coleman taking this tendency to its logical extreme with Free Jazz in 1960), Miles Davis by contrast became famous on 1959’s Kind of Blue for adopting a “modal” form of Jazz, one that counter-intuitively utilizes fewer chords, while playing fewer notes, in deceptively simpler arrangements. Although it is actually far more difficult to play in this manner (especially without the scaffolding of pre-determined chord changes), the Miles Davis Quintet made it sound easy.

Not coincidentally, Kind of Blue also happens to be the best selling Jazz LP of all time—at least 5 million copies sold and counting. It is also no coincidence that Pink Floyd used the Kind of Blue chords as the basis for their similarly-brooding Dark Side of the Moon—the best selling Rock album of all time; nor that Kind of Blue is also cited as a favorite of Quincy Jones, the producer for Michael Jackson’s Thriller—the best selling Pop album of all time. (You can definitely hear Kind of Blue‘s influence on the lack of chord-modulations in the title-track “Thriller“–not to mention “Billy Jean,” whose repeated keyboard-riff sounds suspiciously similar to that of “All Blues“). Something about Davis’s minimalist approach resonates across an incredibly broad register, influencing multiple genres.

Mayhaps that is because, in its empty spaces, Kind of Blue speaks the “unspeakable gift” (2 Cor. 9:15), that which none of us can articulate but all can feel, all can intuit, and all can resonate with. “The Spirit giveth light to every man that cometh into the world” reads D&C 84:46, and hence we can all recognize that same light when we encounter it out in the wild—especially (and paradoxically) when it isn’t being expressed at all.

This less-is-more approach was one that Davis would continue to experiment with throughout his long and storied career: his classic 1960 album Sketches of Spain, for example, dispenses with solos entirely (it’s arguably not even a Jazz album), instead going strictly for mood and tone. His first great Jazz-Rock fusion album, 1969’s In A Silent Way, pares down his virtuoso trumpet playing to a bare minimum, till his horn becomes ethereal, atmospheric, almost dreamlike. Likewise, his 1974 funeral dirge for the late Duke Ellington, “He Loved Him Madly,” was credited by no less than Brian Eno with helping innovate the entire genre of Ambient music.

We could multiply examples. Suffice to say for now, Davis took literally the idea that “The Spirit itself maketh intercession for us with groanings which cannot be uttered” (Romans 8:26), by refusing to utter or speak these groanings in the first place—and thereby creating a space for them to manifest.

And as every missionary knows, people convert to the Gospel not due to anything they said–quite the contrary–but the things they didn’t say, precisely because they couldn’t say it: “the peace of God, which passeth all understanding” (Philippians 4:6). Preach the gospel, and if necessary, use words (so said Elder Holland quoting St. Aquinas). It’s the notes we don’t play. This is why there should be Jazz in Utah–more than just as a mere basketball team.