New parenthood doesn’t just change what you listen to, but how you listen.

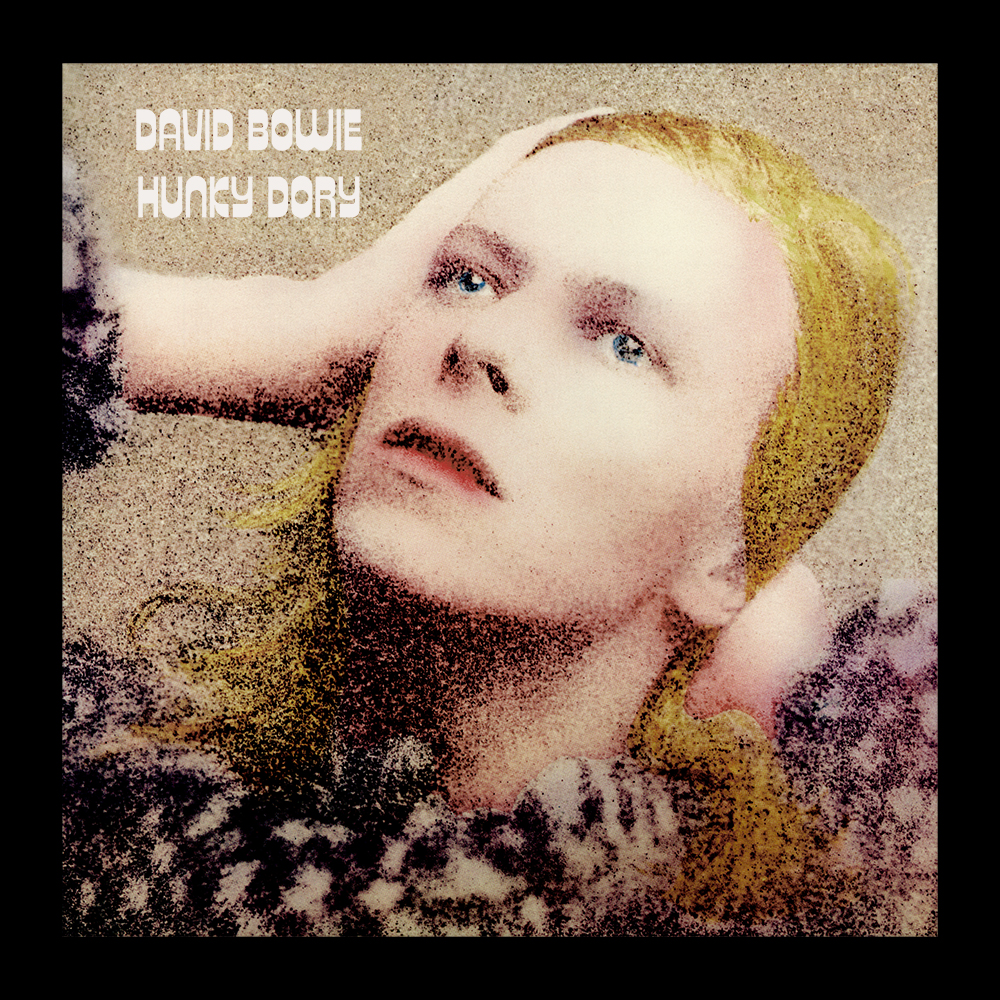

When I was younger and wearing out my copy of David Bowie‘s 1971 glam-rock classic Hunky Dory, for example, it was easy to imagine that he was singing “Kooks” directly to me (“will you stay in a lover’s story/if you stay, you won’t be sorry/cause we believe in you…”), as though he were my surrogate father, or at least articulating what I wanted my parents to say to me. Needless to say however, the moment my first child was born, I began to sing along with Bowie–he now articulating what I wanted to say to my children instead.

In short order, I came to realize that not just “Kooks,” but the whole of Hunky Dory is about the simultaneous joys and anxieties of impending parenthood. That iconic opener “Changes” for example (“turning to face the strange…”) certainly resonates in this completely new context, in any case; no longer was the song about the dramatic changes that come from growing up or graduating or moving out or what have you, but specifically the very strange changes that come from a child being born to you.

David Bowie’s son had actually been born that very year, so I suspect that “Changes” was as reflective of his new parenthood status as “Kooks” was. Indeed, when Bowie sang “and the children that you spit upon as they try to change their worlds/are immune to your consultations, they’re quite aware what they’re going through”[1]famously immortalized by the opening-credits to The Breakfast Club, it suddenly occurred to me that that was as much a reminder to himself, now that he was a new father, as to anyone.

It’s especially apropos for Bowie to be singing about the strangeness of newborns because he had at the time very carefully cultivated a space alien persona–and all newborns look like space aliens, frankly. But then, according to LDS doctrine, we very literally are “strangers and pilgrims” upon this earth, spirit-visitors from another realm, brief sojourners here on our fantastic voyage through the cosmos, with an alien Heavenly Father on another planet at the center of the universe helping us return home.

I don’t mean any of that disparagingly, by the way[2]and given how Bowie’s guitarist at the time Mick Ronson was actually raised Mormon–and whose 1993 funeral services were even held at an LDS London chapel–it’s fun to speculate … Continue reading. On the contrary, I think we waste far too much time trying to “normalize” our faith for mainstream America, that we would actually be better served just owning the oddness of our doctrine, to keep Mormonism weird, to lean into our distinctiveness and “turn and face the strange”, in other words. It’s the only way we’ll grow–both individually and as a Church, I dare say.

Parents also feature prominently in verse 1 of “Life on Mars” (“But her mummy is yelling, No/And her daddy has told her to go”). Moreover, his quiet anxieties that his children will one day displace and surpass him are expressed by the Nietzschean Homo Superior/Superman references in “Oh You Pretty Things” and “Quicksand”. Conversely, his anxieties about the influence of his own forebears and antecedents upon him are expressed in “Andy Warhol” and “Song for Bob Dylan”. Fathers and sons overshadowing and surpassing one another are the overarching anxieties of the LP.

But these anxieties are even more complicated if we return to an LDS context: for if, as Joseph Smith, Jr. claimed in The King Follet Discourse, our spirits are “co-equal” with God’s (and even Joseph Fielding Smith believed that should be rendered “co-eternal”, the same point still stands), then logically our own children are also co-equal and co-eternal with us. In this doctrine, our children have the same capacity for eternal godhood as we–as do our parents. We will no more displace our parents–both our earthly and heavenly–than our children will displace us. This presumed competition for scarce resources is a temporary condition of our fallen world; in the infinite eternities, there will be room for all exaltations.

What exactly will that look like? We have scarcely even begun to speculate, let alone receive revelation on the same. But then, as Bowie sings in Hunky Dory’s haunting closing track “The Bewlay Brothers“, “we were so turned on/by your lack of conclusions…”

References[+]

| ↑1 | famously immortalized by the opening-credits to The Breakfast Club |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | and given how Bowie’s guitarist at the time Mick Ronson was actually raised Mormon–and whose 1993 funeral services were even held at an LDS London chapel–it’s fun to speculate as to whether Bowie had already been exposed directly to this theology |