A couple weeks ago in a post about Jack White’s solo career, I wrote that “To follow Jack White’s post-Stripes career is similar to being a post-’90s Weezer fan—it’s to be constantly grasping at straws, sifting for wheat among the chaff, trying desperately to remind yourself of why you were ever a fan in the first place.” I feel like that could use some more context.

Because you have to understand that there was a point in my life when I actually considered Weezer my favorite band. Like many of my immediate generation, I listened to their legendary 1994 debut The Blue Album more times than is strictly healthy–it was a sort of punk rock for nerds, introverts, the shy yet passionate; how many times have I quit a terrible job with a triumphant “The workers are going home!“; how often have I felt to turn my back on the rat-race with the life-affirming (and eco-critical) “You take your car to work, I’ll take my board/and when you’re out of fuel, I’m still afloat…“; “Undone (The Sweater Song)” recalls some of my friendliest childhood memories; and 1996’s Pinkerton is perhaps the most honest assessment of an awkward young man’s libido ever committed to CD.

Such was the goodwill bought by those 2 brilliant albums that, like far too many Weezer fans my age, I greeted their 2001 comeback The Green Album with joy, rather than the shrug that that 28-minute generic-a-thon probably deserved (hit-single “Island In The Sun” notwithstanding).

A year later, after an unprecedented fan-outreach gimmick that had fans voting online for which new tracks to include, I bought 2002’s Maladroit the day it came out, which I’d never done before nor since. Yet even clear back then, we long-suffering Weezer fans were already having to convince ourselves to “enjoy this music for what it is”, rather than compare it to their ’90s classics–for the truth was that Green and Maladroit didn’t compare to those first twin masterpieces at all–and in our all-too-rare honest moments, we had to admit that, as breezy fun as Green and Maladroit could sometimes be, if it hadn’t been for Blue and Pinkerton, we never would have bothered checking them out in the first place.

Yet still we soldiered on, dutifully purchasing Weezer’s new albums and requesting their newest singles on local radio stations–not for what they were doing, mind you, but what we all expected, all hoped, that they would do. There had been a 5-year hiatus after Pinkerton you see–an album critically and commercially reviled in ’96, before finding second-life as a deeply-revered cult-classic spoken of only in hushed, reverent tones. We all believed that Weezer was still just brushing off the cobwebs, getting their mojo back, regaining their confidence with these tepid new albums after Pinkerton’s frightful rejection–that after tentatively testing the waters and trying their fans’ devotion, they would in short order produce another Blue–or even (we dared dream!) another Pinkerton.

Then I went on my mission, where I thankfully learned to care about things far more important than mere music fandom. Weezer apparently took another hiatus as well, for upon my return home from Latin America I was informed that Weezer still hadn’t released anything since Maladroit. It was when I returned to BYU that Weezer finally dropped their long anticipated follow-up, Make Believe.

The kindest thing I can say about that-which-should-remain-nameless is at least I didn’t pay money for it (a roommate burned me a copy). Oh I tried, for old time’s sake, I really tried to like it! I tried to read “Beverly Hills” as some sort of cheekily-subversive parody of our celebrity-worshiping culture, rather than a symptom of it; I tried to unironically sing-along to “You’re My Best Friend”; I tried to treat “We Are All On Drugs” as an intentional joke.

All for naught. Here at last I could make no more excuses for them, my long-suffering patience was at an end, the last of my ’90s-era goodwill was officially burned away–I had to confess, these songs were just plain awful. The lyrics were trite, lazy, juvenile, and hackneyed; the musicianship was cliched, uninspired, and overwrought; to quote Napoleon, it was worse than a crime, it was a blunder!

My goodness, they take another hiatus and this is the best they could come up with? Seriously, their Harvard-grad frontman took a long, hard look at the direction his band was taking, and his brilliant solution was to go even dumber?! Sweet Mercy, the subpar Green and Maladroit (which merely felt impersonal, not idiotic) were mid-period masterpieces compared to this dreck. The overplay of “Beverly Hills” and “We Are All On Drugs” is part of why I finally quit listening to the radio altogether. Besides, far more interesting and innovative acts–Animal Collective, TV on the Radio, Arcade Fire, Andrew Bird, Interpol, the Strokes, etc.–were arising out of the indie world at the time, so I broke up with Weezer, turned off the radio, and never looked back.

Which I never regretted. I was of course peripherally aware of when the Red, White, and Black albums and Raditude and Hurley and Pacific Coast Dream and assorted B-Side collections and so on and so forth came out over the ensuing years; I think I gave each album’s lead-single a cursory listen on YouTube, if for no other reason than to confirm that there was no reason to return to them. It was like periodically checking in on social media to see how far your ex has descended into a downward spiral–you feel sorry for them, even as you’re glad that you jumped ship when you did.

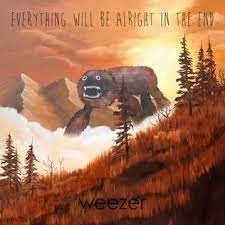

Not that Weezer wasn’t self-aware this entire time they were collapsing into self-parody. 2014’s Everything Will Be Alright In The End for example was a self-conscious attempt to woo back the original core of Weezer fans who jumped ship clear back in the mid-aughts. And like any ex, I found myself at the time unexpectedly open to their wooing, to their offers to forget the sordid past and get back together, to love like we used to.

Yet even as they winkingly sang “Let’s rock like it’s ’94”, I couldn’t help but remember how much better their actual ’94 music was (I never threw away The Blue Album after all). I also couldn’t help but imagine about how much more meaningful this disc would’ve been if they’d released it, say, 10 or even 15 years earlier. Back then I might have thought they were finally getting their act back together, recovering their mojo. But now it’s far too late–I’ve known for awhile that they’re not the same Weezer.

And why? What happened between 1996 and 2000, that began their long, excruciating slide into mediocrity? Why didn’t they get better with age? I’ve been using break-up analogies here half-facetiously, but the truth is, an actual break-up did in fact occur within Weezer post-’96, and it’s the X-factor that has been missing from and haunting Weezer ever since.

His name is Matt Sharp. He was the bassist on their first two albums.

It’s so easy to forget the bassist, isn’t it (just like it was easy to ignore Meg White in The White Stripes). Especially in a Rock band, the bassist is just who keeps the beat, maybe gives some backing vocals. Meanwhile, Rivers Cuomo is the lead singer, lead guitarist, primary song-writer for Weezer–it was always kind of the Rivers Cuomo band, so Matt Sharp was easy to dismiss.

Nevertheless, Matt Sharp was the bassist for Weezer on Blue and Pinkerton–and not on any subsequent album. Not coincidentally, every non-Matt-Sharp album has sucked.

Although Sharp has repeatedly downplayed his impact on the band in various interviews over the years–telling similarly-thinking fans that if had stayed in Weezer past 1998 they probably still would’ve sucked–nevertheless there was clearly doing something to elevate the band. If he maybe was not outright writing these songs, then clearly something about his personality, his aloofness, his goofiness, his coolness, his self-confidence, was grounding and driving and challenging Rivers Cuomo as a songwriter in a manner that he has clearly never experienced since.

Serious, pay especial attention to Matt in the videos for “Buddy Holly” or “Say It Ain’t So” or “El Scorcho” or “The Good Life” or his own music with The Rentals or even his image 2nd-from-right on The Blue Album‘s cover art–there’s just an ambiance about the dude that transcends the group’s whole “nerd-band” schtick, to elevate them into something truly astonishing. I think it is fair to say that Matt-Sharp-Weezer is an utterly different band from Matt-Sharp-less Weezer–and when I say I was once a Weezer fan, I mean only of Matt-Sharp-Weezer.

In fact, I will be so bold as to say that we are still waiting for Weezer to get back together–all this time, we’ve actually only been listening to 3 guys who used to be in Weezer, performing covers of old Weezer songs, whilst trying but failing miserably to write new songs in the same style. The fact that the current line-up is 3/4ths the old Weezer is of no avail; I for one am no longer fooled; Weezer’s post-Pinkerton hiatus is still not over, and will never be over, until Matt Sharp returns to bass.

As I wrote a couple weeks ago concerning The White Stripes: “There is of course a larger moral here: never discount the contributions of those around you, no matter how much less ‘talented’ or ‘skilled’ you may perceive them to be. Never assume that you are ‘self-made,’ or that you ‘never got help from anyone,’ or that you ever accomplished anything ‘all by yourself’ and that ‘others are leaching off your genius’ and other such poisonous rationalizations that soothe the conscious of the rich as they grind on the faces of the poor–for you never completely know who all has helped and enabled you along the way.[…] This interdependence, perhaps not incidentally, is why Mosiah 18:8-10 declares that it is a part of our baptismal covenants to ‘mourn with those that mourn, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort,’ and especially to ‘bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light’–and that, again, not condescendingly, not patronizingly, but with a very real sense of our irrevocable interdependence, and of how that reliance on each other not only sustains us, but is what makes us feel alive.”

We might also add in Weezer’s case that this is why we have scriptural admonitions against “filthy lucre,” to “seek not for riches but for wisdom,” of how “the love of money is the root of all evil.” Make Believe went platinum, while Pinkerton only went Gold.[1]The Blue Album went triple-platinum, but somehow that is never the sweet high they’ve been chasing ever since. Hence it is no accident that it’s been Make Believe, not Pinkerton, that they have been desperately trying to repeat ever since, to increasingly flailing and self-parodying results. (I mean, their only hit in recent years was that 2018 karaoke-cover of Toto’s “Africa”—complete with a music video parodying the original “Undone-The Sweater Song” video, starring none other than Weird Al as Rivers Cuomo). At the risk of cliche, they were obviously chasing the money, not the music.

The early-90s Alternative scene that spawned Weezer, recall, fetishized “authenticity” and “not selling out” to such a wild degree that the backlash was as long-lasting as it was inevitable. Yet all these decades later, as the vicious exploitation of the working class and the third world and of the earth itself by corporations and governments alike continues to worsen, it’s clear now that those were no idle nor juvenile concerns. The pursuit of wealth above all other considerations really is killing us all—yes, even those doing the exploiting; as Malachi warns us, “The Lord will be a swift witness against those who…oppress the hireling in his wages” (Malachi 3:5).

Yet even if every corporation on earth magically behaved ethically—for good PR if nothing else—yet still this pursuit of wealth before all other considerations would have a deadening influence upon our creative sensibilities. Just look what happened to Weezer.

We are all supposed to be creatives, after all—we will one day be creating worlds.