[Apropos of the season, we present here a third and final selection from Modern Death in Irish and Latin American Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), available for order here or here, or as a free pdf download here or here. As with our previous two excerpts, I share this chapter as an example of what’s possible when we allow an LDS perspective to seep into our scholarship, whether explicitly or not. In this case, I here argue that our Christmas gift-exchanges–as I’d previously argued concerning Day of the Dead ofrendas and Halloween trick-or-treating–gesture towards a pre-modern set of economic relations predicated not upon austerity, efficiency, or maximizing production, but upon generosity, liberality, and maximizing human relations.

[Left largely unstated here, of course, is that the set of pre-modern economic relations that I am specifically yearning for here is that of the City of Enoch, Zion, the Law of Consecration, the United Order–what both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young understood to be the only economic system acceptable before God, the same in the beginning as it will be in the end. Whosoever hath ears to hear, let them hear.]

Christmas Ghost Stories

Another important aspect of James Joyce’s “The Dead” that needs to be addressed is the fact that it is not only a ghost story, but specifically a Christmas ghost story—a now-defunct Holiday ritual that was once an integral part of the English-speaking world’s Christmas festivities. As late as 1891, British humorist Jerome K. Jerome could assert with confidence that, “Whenever five or six English-speaking people meet round a fire on Christmas Eve, they start telling each other ghost stories […] Nothing satisfies us on Christmas Eve but to hear each other tell authentic anecdotes about spectres” (Dickey). Evidently in Victorian England—the source of so many other of our modern yuletide traditions—the “scary ghost stories” were as much a hallmark of the Christmas season as the chimney stockings, the trees, the holly, the carols, and the red suits of jolly ol’ St. Nich. Indeed, the Victorians produced a veritable glut of Christmas ghost stories; popular authors of the genre included E.F. Benson, Algernon Blackwood, J.H. Riddell, A.M. Burrage and M.R. James. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was but one prominent exemplar of the same (and wasn’t even the only one he wrote).

For that matter, oft-forgotten is the fact that the framing device of Henry James’ seminal ghost-story The Turn of the Screw is that of Holiday revelers sharing ghost stories around the fire one Christmas Eve: “The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be” (James 1). It was a tradition apparently spanning back centuries; according to Robert A. Davis, “Christmas and Epiphany were, in fact, much more common occasions for hauntings than All Saints and All Souls, suggesting that ghosts regularly took shameless advantage of the meagre leisure time of medieval people” (Davis 38). Lisa Morton in turn argues that during the Medieval period, Halloween and Christmas were part of the same Carnival season: “In some areas, Halloween marked the beginning of the Christmas season, and thus was the time to choose a ‘Lord of Misrule’…to oversee the merriment” (Morton 19). The modern complaint about how there is scarcely any space between the Halloween and Christmas seasons anymore may be far more antiquated than we realize.

In 21st century America however, the sole vestigial remnant of this ghost-story tradition resides in the chorus to Andy Williams’ Holiday supermarket-radio staple “It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year,” where lurks the line: “They’ll be scary ghost stories/and tales of the glories/of Christmases long, long ago”. The 1963 hit likely debuted right towards the tale-end of our collective memory of that storied tradition, which was already fading fast from the consciousness of the postwar generation. Given the genre’s immense influence upon English letters, it is worth inquiring why the Christmas ghost story disappeared so completely from the Anglosphere—as well as why it existed in the first place.

From Hamlet to Holden

There is perhaps a hint as to why the English once so freely indulged in ghost stories come Christmas time in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, wherein Marcellus, the palace guard who first spies the ghost of King Hamlet on a “bitter cold” (perhaps December?) night, ponders aloud:

Some say that ever ‘gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated

The bird of dawning singeth all night long

And then, they say, no spirit dares stir abroad

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm

So hallow’d and so gracious is the time (Hamlet Act I.i.181-187)

Now, perhaps Marcellus here is simply running his mouth in a frothing panic, just trying to recall to his mind all the disparate ghost-lore he knows in order to understand this fearsome apparition; or, perhaps Marcellus is simply astounded the ghost had the temerity—nay, the capacity—to appear at all. For as he understands it, during Christmas, “no spirit dares stir abroad, no fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm.” That is, the Christmas “season…Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated” is when “no spirit dares stir abroad,” when the ghosts have the least power to walk the Earth. It can be potentially inferred that the English only dared to tell ghost stories at Christmas because they believed that was when the ghosts had the least power to haunt them.

By extension, in Joyce’s “The Dead”, Gabriel Conroy is perhaps stunned by the intrusion of Michael Fury into his life because he had also presumed that ghosts had the least power to haunt him on Christmas. Similar to how Ebenezer Scrooge initially refuses to believe his own eyes when the ghost of Jacob Marley appears to him (blithely insisting that “There is more gravey than the grave about you” before Marley’s shriek brings him to his knees), Gabriel Conroy is unable to imagine even the possibility of ghosts; both characters’ predominantly Anglo-Protestant epistemologies excluded the dead as they did all other populations deemed economically unproductive, surplus, and superfluous—“If they would rather die…they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population,” as Scrooge also says of the starving poor, and the dead are almost by definition economically unproductive. In each case, their spectral encounter with a revenant has the effect pivoting the protagonist away from their Anglo-Protestant frameworks: Gabriel Conroy (as I argued in Chapter 5) experiences the first stirrings of an anti-colonial consciousness after his encounter with the dead, while Scrooge abandons cold economic austerity and efficiency in favor of a more humane generosity and liberality.

This resistance against the demands of the ultra-competitive market economy is likewise foregrounded in 1951’s The Catcher in the Rye, which (and I do not believe this is emphasized nearly enough) can also be read as first and foremost a Christmas ghost story. J.D. Salinger’s lone novel opens at the end of a Fall Semester—that is, during the Christmas holiday season. As private-school wash-out Holden Caufield meanders about New York City while he avoids heading home, he is depressed to overhear men swearing profusely as they unload a Christmas tree off a truck; he drunkenly calls his crush Sally Hayes to follow up her offer to trim the tree together; he buys a record for his younger sister Phoebe as a Christmas gift—who in turn good-heartedly lends him her own Christmas gift money when she learns of his indignant state. More interestingly, Holden’s morose and self-destructive behavior is revealed to be rooted in the same cause as Prince Hamlet: he is grieving—in this case, for Allie Caufield, the 11-year-old younger brother who had recently succumbed to leukemia. Holden even goes so far as to idealize Allie as a spectral presence watching over him:

“Anyway, I kept walking and walking up Fifth Avenue, without any tie on or anything. Then all of a sudden, something very spooky started happening. Every time I came to the end of a block and stepped off the goddam curb, I had this feeling that I’d never get to the other side of the street. I thought I’d just go down, down, down, and nobody’d ever see me again. Boy, did it scare me. You can’t imagine. I started sweating like a bastard—my whole shirt and underwear and everything. Then I started doing something else. Every time I’d get to the end of a block I’d make believe I was talking to my brother Allie. I’d say to him, ‘Allie, don’t let me disappear. Allie, don’t let me disappear. Allie, don’t let me disappear. Please, Allie.’ And then when I’d reach the other side of the street without disappearing, I’d thank him.” (217-218)

The ghost of Allie Caufield haunts over the entire proceedings of the novel; and it is no coincidence that Holden invokes him in particular during the Christmas season, the one time of year when the English-speaking world once most indulged in ghost stories. Significantly, Holden even prays to the ghost of Allie Caulfield to watch over him; he neither dismisses his presence as illusory nor fears him as frightening. Holden’s ghostly invocations of Allie Caulfield gesture towards his own resistance against the present economic order: his repeated teenage declamations against societal “phoniness”, his desire to withdraw to a cabin in the woods, his willfully-poor academic performance, and his frustration at his older brother D.B. “prostituting” his literary talents for Hollywood, likewise signal his larger rejection of the productivity demands of the market economy (even as he largely fails to withdraw from it himself). That is, Holden calls upon the ghosts because he has not rejected them as unproductive—largely because he has not rejected himself for being unproductive.

It is of course no mystery as to why the ghosts chose Christmas as the apropos time to challenge the demands of the market economy: the gift-exchanges central to Christmas celebration gesture towards the possibility of re-establishing a pre-modern set of economic relations, ones centered not upon the maximization of production, but upon forming a genuinely generous, humane, and egalitarian society. Indeed, the economics of gift-exchanges is where Christmas intersects with Halloween and Day of the Dead; in Chapter 2, I cited Jean Baudrillard, who argued in The Mirror of Production that the aim of labor and gift-exchanges in premodern societies was not production for its own sake, but on creating an equilibrium with the earth and with each other: “This taking and returning, giving and receiving, is essential” (83). The goal was never to produce a profit or a surplus, but to seal together a relationship. I earlier argued that trick-or-treating and the ofrendas at least implicitly revive—if only for a night—this ancient economy of gift-exchange, even if the practice has by now been completely co-opted by late-capitalist production.

Similarly, no matter how thoroughly Christmas gift-exchanges have also become assimilated by and integrated into our late-capitalist society, gift-exchanges nevertheless remain at bottom a practice that is fundamentally opposed to the present economic order. In A Christmas Carol, for example, Dickens describes a London holiday market wherein “Poulterers’ and grocers’ trades became a splendid joke: a glorious pageant, with which it was next to impossible to believe that such dull principles as bargain and sale had anything to do” (15-16); in the heart of that most market-oriented “nation of shopkeepers”, Christmas, however briefly, overturned the primacy of purely economic relations—as Bakhtin might say, “people were reborn for human relations” (9).

As T.S. Eliot also states in his 1954 poem “The Cultivation of Christmas Trees” (written well into the period of his own Anglo-Catholic rejection of modernity), “There are several attitudes towards Christmas/Some of which we may disregard/The social, the torpid, the patently commercial” (107), which commercialism Eliot dismisses as a modern innovation, one that is patently alien to the core Christmas holiday. Even the very iconography of modern Christmas itself remains aggressively anti-modern: the trees and lights of Saturnalia; the cattle, shepherds, and angelic hosts of the two-millennia old Nativity story; the horse-drawn sleighs and Victorian-style lanterns; the stockings over the fireplace and wreaths of holly; the hopelessly anachronistic use of the adjective “Merry”—all indicate a stubborn resistance against modernity by Christmas even as it is thoroughly absorbed by the same.

For that matter, the Christ Jesus at the heart of Christmas likewise potentializes a fundamentally alien economy: Jesus’s miracles of the loaves and the fishes, for example—wherein 5,000 congregants are miraculously fed through the radical expansion of seven fishes and five loaves of bread (such that 12 baskets make up the excess), all of which is made freely available without labor or payment—renders the very categories of surplus and scarcity functionally meaningless. The miracle opens up the tantalizing possibility for a post-scarcity economic order wherein it is impossible for basic necessities to be earned, rationed, or distributed since they are all produced freely in excess.

Such a set of economic factors would in turn undermine the very basis for all forms of market economy—for that matter, so too does the infinite and eternal Atonement of Christ, wherein God’s Grace is made freely available to all, “without money and without price” (KJV Isaiah 55:1). Evidently among the very earliest generation of believers, there were attempts to translate this heavenly economy into an earthly one: the Apostles upon the Feast of Pentecost, recall, organized a community whose members “had all things common; and sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need” (KJV Acts 2:44-45). It is of course not a novel insight to observe that Christendom has scarcely ever managed to live up to such lofty ideals since, nor that its adherents have become as categorically appropriated by late-capitalism as Christmas or anything else for that matter. But nor is it out of line to note that in the faith’s foundational documents, Christianity attempted to establish an economic order utterly hostile to our present one—nor that Christmas itself attempts to re-enact it (at least in limited doses) every December.

G.K. Chesterton’s Christmas Carol

Of course, anyone who has read A Christmas Carol is already well aware that the Holiday already possesses a deep-seated suspicion of unregulated market logic. As Catholic-apologist and popular-essayist G.K. Chesterton argued in his introduction to a 1922 edition of Dickens’ novel, “If a little more success had crowned the Puritan movement of the seventeenth century, or the Utilitarian movement of the nineteenth century, these things would…have become merely details of the neglected past, a part of history or even archeology. The very word Christmas would now sound like the word Candlemas” (vii). It was precisely the anti-modernity of Christmas, according to Chesterton, that renders it so incompatible with economic utilitarianism and materialism, such that its survival into the 20th century (let alone the 21st) was by no means a given. Moreover, Scrooge for Chesterton is not just a character, but a type:

“Scrooge…is a miser in theory as well as in practice. He utters all the sophistries by which the age of machinery has tried to turn the virtue of charity into a vice…Many amiable sociologists will say, as he said, ‘Let them die and decrease the surplus population’… It is notable also that Dickens gives the right reply…The answer to anyone who talks about the surplus population is to ask him whether he is the surplus population…That is the answer which the Spirit of Christmas gives to Scrooge…Scrooge is exactly the sort of man who would really talk of the superfluous poor as of something dim and distant; and yet he is also exactly the sort of man whom others might regard as sufficiently dim, not to say dingy, to be himself superfluous…the miser who himself looks so like a pauper, confidently ordering the massacre of paupers.” (x)

When Ebenezer Scrooge sneers of the poor, “If they would rather die…they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population,” he is speaking not only for himself, but an entire ethos in Industrial Revolution-era England that deemed all forms of excess—peoples and holidays alike—as excisable. When Dickens (according to Chesterton) inquires as to whether Scrooge himself is not among the “surplus population”, he is challenging the very idea that any human beings should ever be treated as expendable in the first place. These were not idle, theoretical considerations; as discussed in the Introduction, Christmas Carol was published in December 1843, less than two years before the outbreak of the Potato Famine, wherein over a million Irish peasants were deemed excess population by English Parliament, unmeriting of even basic humanitarian aid or relief—all while the bumper crops continued to be shipped over to England under armed guard. Chesterton himself notes how thoroughly this sort of logic had already ingratiated itself with the various and sundry Eugenicists, social Darwinists, armchair-Nietzscheans, and nascent-fascists already making the rounds in 1922, who even then were laying the groundwork for WWII and the Holocaust:

“This is true enough even to more modern life; and we have all met mental defectives in the comfortable classes who are humoured, as with a kind of hobby, by being allowed to go about lecturing on the mental deficiency of poor people. We have all met professors, of stunted figure and the most startling ugliness, who explain that all save the strong and beautiful should be painlessly extinguished in the interests of the race. We have all seen the most sedentary scholars proving on paper that none should survive save the victors of aggressive war and physical struggle of life; we have all heard the idle rich explaining why the idle poor deserve to be left to die of hunger. In all the spirit of Scrooge survives.

“But in justice to Scrooge, we must admit that in some respects the later developments of his heathen philosophy have gone beyond him. If Scrooge was an individualist, he had something of the good as well as the evil of individualism. He believed at least in the negative liberty of the Utilitarians. He was ready to live and let live, even if the standard of living was very near to that of dying and letting die. He partook of gruel while his nephew partook of punch; but it never occurred to him that he should forcibly forbid a grown man like his nephew to consume punch, or coerce him into eating gruel. In that he was far behind the ferocity and tyranny of the social reformers of our own day. If he refused to subscribe to a scheme for giving people Christmas dinners, at least he did not subscribe (as the reformers do) to a scheme for taking away the Christmas dinners they have already got…Doubtless he would have regarded charity as folly, but he would also have regarded the forcible reversal as theft. He would not have thought it natural to pursue Bob Cratchit to his own home, to spy on him, to steal his turkey, to run away with his punch-bowl, to kidnap his crippled child, and put him in prison as a defective…These antics were far beyond the activities of poor Scrooge, whose figure shines by comparison with something of humour and humanity.” (x-xi)

For Chesterton, Scrooge’s callous indifference of the poor is almost good-humored compared to the “social reformers” of his own day, who did not merely neglect the poor, but actively called for their extermination—and considered such a policy “progressive”. Remember that in 1922 Chesterton also penned a treatise entitled Eugenics and Other Evils (well before the Nazis had rendered eugenics a dirty-word), and for which Chesterton was lambasted as reactionary and conservative. (Indeed, such progressive luminaries as George Bernard Shaw and Theodore Roosevelt were unfortunately themselves vocal supporters of eugenics.)

But then, all that separated Scrooge from the eugenicists was a difference of degree, not of kind; in both cases, they sought to purge human society of all excess and surplus—and the only real disagreement was on whether it was more efficient to purge them by means of laissez-faire capitalism, the gulags, or the death camps. This mania for efficiency above all other considerations had infected the full breadth of both the Left- and Right-wing ideologies throughout the Modernist period—and according to Chesterton, that arch-Victorian Dickens had anticipated them all.

Chesterton consequently praises Christmas as a bulwark against such fundamental viciousness, and reads its survival into modernity as an act of defiance against the same; but that is not to say that Christmas has survived unscathed. Today, complaining about the commercialization of Christmas is as clichéd as Christmas itself is. Its integration into late-capitalism has been so complete that retailers now matter-of-factly depend upon the Holiday shopping season to ensure their own annual survival (one theory for the origin of the term “Black Friday” is that the launch of the Holiday shopping season is when most retailers’ annual profits finally go “into the black”). As with Halloween and Day of the Dead, the global market’s victory over Christmas has been near-total.

I dare say that contemporary Christmas today would have met a pre-conversion Scrooge’s full approval; his former outlook ultimately won the day. It is also worth noting that Scrooge’s humanitarian transformation at novel’s end is only ever allowed to occur at Christmas time—just as the ghosts used to be—and for the same reason: in the Anglosphere, Christmas is when altruism has the least ability to haunt us.

Yet despite all attempts to bury that altruistic impulse beneath an avalanche of consumerism, it is never eradicated entirely; and even if so many of our gift-exchanges only pay lip-service at best to an alternative economy of human fellowship and generosity, still that lip-service is present, the embers of which still have the potential to be revived. As Scrooge’s nephew argues, it is “the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys” (9); though that statement perhaps speaks poorly to the generosity of the English nation the whole rest of the year, nevertheless it still speaks to a native humanity that but awaits the right conditions to re-exert itself. Altruism and the ideal of egalitarianism are no more completely disappeared than the dead are; they can return to disrupt us as much as the dead can. For that matter, the scary ghost stories have not completely disappeared from Christmas either.

The Nightmare Before Christmas

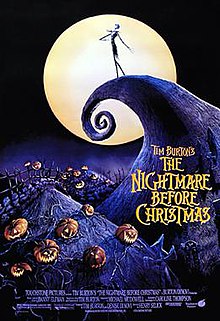

To be clear, by the end of the 20th century, the ghosts had been exorcised almost entirely from English and Anglo-American Christmas festivities—such that when Tim Burton’s cult-classic The Nightmare Before Christmas debuted in 1993, part of its selling-point was just how delightfully deviant it would be to combine Halloween with Christmas, how incongruous it must be to mix the Yuletide with the graveyard. (Disney even released the film through their Touchstone label, fearing that the subject matter would be “too scary” for their own family-friendly imprint).

The stop-motion film imagines a fairy-tale world wherein each North American Holiday inhabits its own dream-land metropole. In Halloween Town, the patron spirit Jack Skellington develops a profound malaise over how their annual Halloween celebrations never vary, never alter, year in and year out. While pacing through the woods at the end of yet another Halloween, he stumbles upon the entrance to Christmas Town. Enchanted and invigorated by the magical sights he sees there, he develops a plan for Halloween Town to commandeer Christmas for themselves, so that they too may experience that same magical feeling.

However, despite Skellington’s best intentions, the horror-themed denizens of Halloween Town inadvertently produce a macabre vision of the holiday, complete with haunted toys, flying-reindeer skeletons, and Skellington himself taking the place of Santa Claus, whom he has had kidnapped. On Christmas Eve, the various ghoulish gifts he leaves in people’s homes spread such wide-spread terror that his sleigh is shot out of the sky by military anti-aircraft cannons. Realizing the error of his hubris, Skellington rushes to rescue the kidnapped Santa Claus from the devious Oogie-Boogie Man, so that he might save Christmas before it’s too late. Nightmare was not only the last great exemplar of the lost art of stop-motion animation, but perhaps also the final gasp of the Christmas ghost story.

Yet as charming as the film’s set-designs, Daniel Elfman soundtrack, and childlike dream-logic can be, one could also argue that there is something inherently conservative, even authoritarian, about Nightmare: for the film’s very deviancy appears rooted in the conviction that these holidays must not overlap, that their clear boundaries must not be transgressed, and that the full force of the U.S. military must be deployed to enforce them. “Secure our borders” could very well be the ethos of the film.

Nevertheless, such a reading has scarcely ever been proposed for Nightmare, and is unlikely to gain traction even now, for the simple fact that the film itself does not seem to share it: the film concludes with Santa Claus himself voluntarily participating in the blending of the two holidays, as he causes snow to fall for the first time upon the delighted citizens of Halloween Town. “Happy Halloween!” he shouts merrily from his sled flying overhead, as Jack Skellington calls back “Merry Christmas!” Moreover, on the official soundtrack, there appears an extra track cut from the film, wherein Santa Claus, confessing himself to still be “rather fond of that skeleton man,” determines to pay Skellington a visit years later. As they recall together the events of Nightmare, Santa asks Jack if he would do it all over again, “knowing what you knew then, knowing what you know now”, to which Skellington responds with a grin, “Wouldn’t you?”

The film seems to suggest that Skellington’s sin was not that he sought to transgress the boundaries between Holidays, but only how; perhaps a more accurate and generous reading of Nightmare is not that Halloween and Christmas should remain rigidly separate, but that one should never forcefully colonize or appropriate another’s culture without their consent and cooperation. For in the end, despite his blunders, Skellington did in fact achieve his goal of bringing the two holidays together across the borderlands—not only within the fictional universe of the film, but within U.S. pop-culture as well, as the film’s enduring popularity has blended the two holidays together in the popular imagination.

The two holidays were already blended within the imagination of Burton personally. An L.A. Times profile on Burton published at the time of the film’s release notes that, “For Burton, who had been a lonely child growing up in Burbank, holidays were a time of wonder and escape. ‘Anytime there was Christmas or Halloween, you’d go to Thrifty’s and buy stuff and it was great,’ he recalls. ‘It gave you some sort of texture all of a sudden that wasn’t there before’” (Simpson). Embedded in this account is an explanation for the perennial appeal of both Christmas and Halloween: the two holidays provide a temporal break and disruption from the utter homogenization, alienation, and flattening of consumer culture endemic to late-period capitalism, “[giving] you some sort of texture…that wasn’t there before.”

Again, that is certainly not to say that Christmas and Halloween themselves haven’t been utterly flattened and homogenized as well; but it is to say that Christmas, as I have previously argued for Halloween and Day of the Dead, is likewise involved in a quiet resistance of sorts, as it foregrounds the possibility of an alternative economy that belies the prevailing order’s utter hegemony. And in the case of both Christmas and Halloween, it is the ghosts who accomplish it.

Nightmare ends with Skellington embracing his lover Sally amidst a snow-covered graveyard; it is a love story that may feel rather tacked-on from a plot-perspective, but that thematically fits in well with the film’s larger motif of reconciliation—especially the reconciliation between Christmas and Halloween. Morton argued that once upon a time, Halloween marked the beginning of the Christmas season; ever since The Nightmare Before Christmas, it has done so once more. “There’ll be scary ghost stories,” sang Andy Williams; perhaps there could be again.

Bibliography

Bakhtin, Mikael. Rabelais and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. Indiana University Press: 1999.

Baudrillard, Jean. The Mirror of Production. Trans. Mark Poster. Telos Press Ltd., 1975.

Holy Bible, King James Version. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1978.

Chesterton, G.K. “Introduction.” A Christmas Carol. Arcturus, 2011.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Arcturus, 2011.

Dickey, Colin. “A Plea to Resurrect the Christmas Tradition of Telling Ghost Stories.” Smithsonianmag.com. 15 December 2017.

Eliot, T.S. T.S. Eliot: Collected Poems, 1909-1962. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1991.

James, Henry. The Turn of the Screw. Tribeca: 2014.

Morton, Lisa. Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween. Reaktion Books: 2012.

Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. Little, Brown and Company: 1991.

Shakespeare, William. “Hamlet.” The Complete Works of William Shakespeare. Norton: 2016.

Simpson, Blaise. “The Concept: Jack-o’-Santa: Tim Burton’s new movie for Disney isn’t exactly a steal-Christmas-kind-of-thing. It’s more like a borrow-it-and-give-it-a-weird-twist-kind-of-thing.” LA Times. 10 October 1993.

Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. Dir. Henry Selick. Touchstone Pictures: 1993.

Williams, Andy. “The Most Wonderful Time of the Year.” The Andy Williams Christmas Album. Columbia Records, 1963, track 4.