I of course knew nothing about Manny Fox the one and only time I met him; only years later would the obituaries inform me that he was some sort of Broadway legend, a prolific producer and director who had worked with the likes of Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, George Burns, Orson Welles, Barbara Streisand, Johnny Cash, Salvador Dali, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, and numerous other leading lights of the 20th century.

But then, I was only 19 years old, raised in a small town roughly 3,000 miles away from Broadway, and an LDS missionary serving on the island of Puerto Rico.

I was then in my first area, the stunning coastal city of Humacao; the F-14s in those days still flew high overhead to practice bombing runs on nearby Isla de Vieques (“Paz para Vieques” was a common tag on highway underpasses, though unbeknownst to all, the Naval base would soon close for good). As is so often the case in Latin America, Humacao’s poorest area—a small fishing barrio called Buena Vista, where the chickens freely wandered the dirt roads—sat next to its richest: an expansive, expensive resort called Palmas del Mar. Though we tracted through Buena Vista on the regular, I only ever made the trek over to Palmas del Mar twice.

And with good reason: the opulent mansions, the BMWs and Mercedes-Benzes, the gated security, the lavish swimming pools and private palm trees and all those other accouterments of obscene wealth, intimidated me immediately—as indeed they were designed to. Fresh out of High School and with still only a tenuous grasp of the Spanish language, I still felt keenly what it was not to belong. Even after a group of us missionaries somehow talked our way past the front gate (to this day I’m not sure how we pulled that off), I was wary. Nevertheless, after we all paired off for exchanges, I sucked it up and started street contacting.

As my companion and I walked along the pavement in that blazing hot sun, we ran across an elderly gentleman in shorts, sandals, fedora, and a button-down guyabera, out on his morning constitutional. He had a newspaper folded under one arm and a coffee mug in his hand. His hat and sunglasses obscured his features, so I instinctively assumed him Puerto Rican as I called out a jovial “Bueno’ dia’ señor.” Yet even as the words left my mouth, I spied not one but two fat cigars between his fingers. This here was money.

I was paired off that day with a Salvadorean-American from Texas named Elder Rovira—tall, jet-black hair, brown-skinned, he was very clearly Latino himself (and I myself still pale white), which I mention only to explain our confusion when this man replied to us in thick New York English: “Well, well, well, looks like we got ourselves a pair of good ol’ Jewish boys out preachin’ the word today!” Rovira and I glanced at each other, briefly baffled.

Before we could formulate a response, he barreled forward with: “Ya know, someone once said that the last good Christian died on the cross; that is, no one since—or at least not enough folks, ya see—have lived up to his teachings, so to speak. What do you say to that?”

By then we’d recovered and fallen back on script: “Well, funny you should mention that sir, because we actually have a message to share about Jesus Christ today.”

I guess he was game that day, for he shot back: “How fast can you give me this message of yours?”

“10 minutes,” I blurted out, though I’d yet to teach a first discussion in under 20.

“Can you do it in 5?”

Now I was game, and I like to think I half-smiled as I said, “You bet.”

“Walk with me.”

Shortly thereafter, we were lounging in the shade of his car port (a peculiarly Puerto Rican affect, though he was not Puerto Rican himself). He introduced himself as Manny Fox, Broadway producer and director extraordinaire, and pulled us up a couple of chairs as he got on speakerphone with his secretary. “Carol, I’m out here with—what’s your names?” he asked.

“Well, I’m Elder—”

“No, no, your names, your real names,” he said, as though there were such a thing.

“Um, well, I’m Jacob,” I stammered, which suddenly sounded so strange in my mouth—it was then that I realized I didn’t even know my companion’s first name—“And, uh, I’m Frank,” Rovira said, which marked the first and last time on either of our missions that we gave out our first names on a first meeting.

“Carol, I’m out here with Frank and Jacob,” he announced into his phone, “Hold all my calls.” To this day I wonder if he actually had any calls to hold, or if he even had a secretary, or if it was all just an act—and given his theater background, I wouldn’t have been surprised by any or all of the above.

I launched right into the same standard spiel and chain-of-logic I gave countless times throughout my mission—that there is a God and Jesus Christ died for our sins so we could return to him, that God has always sent Prophets to preach of Christ, that one of those Prophets was Joseph Smith, and that The Book of Mormon is evidence of this, and if your read it and pray about it, then you will know by the power of the Holy Ghost and etc.

Truth be told, it was kind of exhilarating, even a relief, to be forced strip our message down to its barest elements, to cram it all in under only 5 wild minutes. Most of us missionaries back then (and I was among the worst offenders) were rambling on for 20 minutes at least, sometimes a full hour, on a first discussion. The LDS Church mission program was still nearly 2 years away from rolling out Preach My Gospel and instructing all missionaries to make 10 minute lessons de rigueur—and I was still several months away from having the same epiphany myself, of how I needed to get out of the way of the Holy Spirit and the peace which surpasseth understanding, the only things that matter. So Mr. Fox at least helped to nudge me in the right direction, if nothing else.

In any case, after he patiently let us finish our spiel, he took this opportunity to network, as he asked us, “if anybody in your organization is wealthy, has the big bucks?”

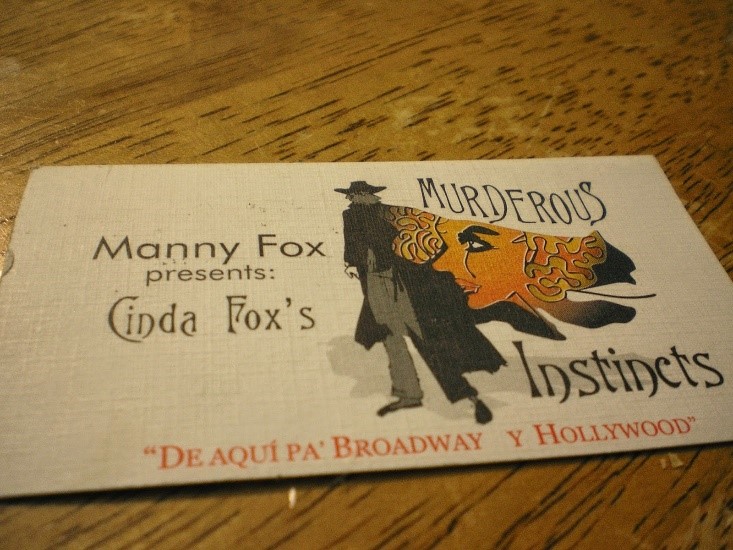

We initially thought maybe he was interrogating whether our Church membership really lives up to its ideals of Christian service and care for the poor (a valid question, frankly, but more on that in a moment)—but no, he was looking for donors: “We here are trying to get financing for Murderous Instincts, you see,” he said as he handed me a business card that I only recently realized I still have, “Our goal is to make it the first play to be fully produced here in Puerto Rico—to then go to Broadway—then on to Hollywood, Lord willing! ‘De aqui pa’ Broadway y Hollywood.’ Lord willing!”

He then (I suppose to assure us he was on the level) opened up the newspaper he’d had tucked under his arm; it was the English edition of the The San Juan Star, for whom he’d written a column entitled “Diary of a Producer.” The press photo was the same as near the top of this post. We were suitably impressed.

Anyways, there were no follow-up appointments. We did leave him a Book of Mormon that he either promptly threw in the garbage or stashed on some forgotten bookshelf—at least until his estate was executed 10 years later (for time works immutably on rich and poor alike), at which point it was then thrown in the garbage, or passed into the hands of someone else, for the Lord worketh in mysterious ways.

Indeed, as is inevitable in any discussion on the intersection of Mormonism and Broadway, I must here note that roughly a year before he passed, a Book of Mormon musical famously debuted in New York (though he surely had as little to do with it as I), the details of which scarcely need to be rehearsed here: of how, in a parody of Broadway musicals generally, the play featured a set of comically naïve Mormon missionaries in over their heads proselyting amongst a grotesquely-exaggerated pantomime of African Third-World poverty; of how the Church leadership took the high-road by refusing to protest it (all while many of the rank-and-file still quietly seethed), even making the surprisingly cheeky move of buying ad-space on the playbill; of how the show swept the Tonys, becoming one of the smash-hits of the decade; all while our provisional allies on the Christian Right couldn’t help but note that if a Broadway play had made such a gleeful mockery of, say, Muslims or Jews, it would never have flown.

Ironically, this conservative critique would prove prescient—albeit in a round-about way that they largely never anticipated. For on the heels of the fall-out of the George Floyd protests and reinvigorated Black Lives Matter movement of 2020, certain Book of Mormon cast-members began to openly confess and acknowledge that the show’s portrayal of Africans was, quite frankly, patronizing, condescending, and borderline racist, feeding into larger colonialist narratives of the African continent entire as an irredeemable hell-hole—narratives that had been used over a century prior to rationalize the unspeakable atrocities of European imperialism, to erase the impressive cultural and industrial achievements of that massively diverse continent, and that had even been used by white-supremacists to retroactively defend American slavery as a mercy clear down to the present day.

Of course, I feel like I could’ve told them that. Many folks could’ve. I dare say that the first time I heard “Sal’ Tlake City” on a CD-R an ex-roommate burned me, I picked up quite quickly the rather obvious racist/colonialist subtext of that production. At times, I wondered in frustration why no high-ranking members of Church leadership didn’t just straight up call the production out on it—that if getting the broader public to care about fair representation of Mormonism in media was a non-starter, then maybe they should at least care about that of Africans.

But of course that thought was overwhelmingly naïve on my part as well: as a certain satirical line from Book of Mormon’s show-stopper “I Believe” reminds us, the racial history of the Church pre-1978 is nothing to crow about, either. Indeed, previous generations of Church leaders had even pulled from that exact same well of European colonial representations to justify our racial Priesthood bans, forcing the 21st century First Presidency to disavow as “folk doctrines” Post Hoc rationalizations for the same that had been taught as Gospel Truth only a half-century earlier. Nor have we yet fully cleansed the inward vessel: recall for example how four years before George Floyd’s murder, the Church dedicated two separate sessions of October General Conference to the plight of the Syrian refugees, rolling out the “I Was a Stranger” Program to fulfill the demands of “pure religion, undefiled before God” in caring for the most destitute among us.

I am not alone in remembering it as one of the most inspiring and moving General Conferences of my lifetime, one that recalled how Brigham Young once cancelled Conference to send the Saints out to rescue the Willie Martin Handcart company trapped on the plains with a fiery: “I will tell you all that your faith, religion, and profession of religion, will never save one soul of you in the Celestial Kingdom of our God, unless you carry out just such principles as I am now teaching you. Go and bring in those people now on the plains. And attend strictly to those things which we call temporal, or temporal duties. Otherwise, your faith will be in vain. The preaching you have heard will be in vain to you, and you will sink to Hell, unless you attend to the things we tell you.” I must also here remind us that this was likewise the year when the First Presidency released official statements about loving our Muslim neighbors, and advocating for immigration law reforms that keep families together, not tear them apart.

Yet scarcely a month after that stirring October Conference, well over half the self-identifying U.S. members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints behaved as though these statements had never been uttered; I watched as faithful, upstanding members I’d known my whole life, who had piously drilled into me and the rest of the Youth of Zion since a young age to “Follow the Prophet” and let the consequence follow, quite matter-of-factly voted instead for the candidate who based his entire platform on denying the Syrian refugees entry, demonizing Muslim-Americans, walling off immigrants, and instituting family separation policies at the border (not to mention later calling black-majority nations “s***holes”). As a teen in the ‘90s, I remembered chaffing against the stern, self-righteous judgmentalism of these my elders—tsk-tsking how we dressed, what music we listened to, what R-rated movies we watched—yet when the signal moment came, when the clarion call to follow the Higher Law arrived, they balked. In the seething silence of my mind, I raged against these whited walls, these painted sepulchers, who had strained at a gnat and swallowed a camel; had tried to pluck a mote from our eyes while behold a beam was in theirs; who had tithed a mint, yet have neglected the weightier matters of the law, justice and mercy and faith; they had been weighed in the balance and found wanting. It was an election that caused me to ponder anew, lo all these many years later, Manny Fox’s opening salvo of “the last good Christian died on the cross…”

Yet further complicating things is the fact that (thanks to grad school) I now know that “the last good Christian died on the cross” was first formulated by Friderich Nietzsche, in his 1895 treatise Anti-Christ: “At bottom there was only one Christian, and he died on the cross…. It is an error amounting to nonsensicality to see in ‘faith’, and particularly in faith in salvation through Christ, the distinguishing mark of the Christian: only the Christian way of life, the life lived by him who died on the cross, is Christian”, he writes. These are hard words to argue with. Yet Nietzsche has sins of his own to answer to for, doesn’t he: his concept of “will-to-power” was appropriated less than a half-century later by the German Nazi regime to philosophically rationalize and validate their own most evil atrocities.

I have of course (like many of you) encountered Nietzsche apologists galore who argue that he, the original Übermensch, would have been horrified to behold how his theories had been twisted into such abject monstrosity—how he is on record as categorically denouncing German antisemitism, even willfully ending his friendship with Richard Wagner at the height of the composer’s celebrity, due the latter’s anti-Jewish prejudices—but I still wonder, frankly. I mean, someone who claims that “The weak and the botched shall perish: first principle of our charity. And one should help them to it”, can only be afforded so much plausible deniability. The Nazis may have deployed this philosophy towards their own monstrous ends, but it’s not like there was a whole lot to misinterpret there in the first place—and it’s not like there aren’t still plenty of people arguing that oppressing the poor is actually a charitable act today.

Ah, but now here I am committing the exact same sin, aren’t I! Over the course of the past 5 paragraphs, I have been unremittingly, hypocritically judgmental—against the hypocrisies of the Book of Mormon musical, against the hypocrisies of my own Church, against the hypocrisies of Nietzschean philosophy—all of which I have tried to present as the plain facts, the banality of evil. Yet though the politics are flipped, the tables turned, still I am violating that most basic and primal of Christ’s injunctions: “Judge not, lest ye be judged”. Try as I might to argue with myself, about how their sins are far worse, yet never did theirs excuse my own. To be the lesser of two evils is still to be evil. As Seneca said, “It is not goodness to be better than the worst”. To point out other’s hypocrisies is to still be a hypocrite.

But it’s just such an easy sin to fall into! I have even dared tell myself that I simply follow the example of Christ in judging these others—did not the Savior vociferously denounce the hypocrisies of the Scribes and Pharisees? Did not the Christ flip over the tables of the money-changers and cleanse them from the Temple with a whip? Am I not to follow the perfect example of the Savior in all things? I even have great reason to, of course; I look into the weary faces of my junior college students here in upstate New Jersey (incidentally, I live much closer to Broadway nowadays)—at these Muslims slandered as terrorists, Mexicans libeled as rapists, DACA kids threatened with deportation to nations they’ve never known, Black students living under the heavy knowledge that the police can kill them with impunity, and all manner of immigrants, refugees, “strangers in the land”—and think that if these are not “the least of these”, if they are not worth fighting for, then who the hell is? And who are these co-congregants of mine who so readily and callously throw them under the bus, in flagrant violation of everything Christ said or did? But even as I feel the great importance of standing up for the poor and despised, I feel as well the sting of the divine injunction “to judge not, lest thou be judged. For with what judgment ye judge, ye shall be judged: and with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.”

And all I can think in such moments is: Damn. It really is impossible to be a Christian. Maybe Nietzsche was right after all.

It is in times like these that I suddenly start to appreciate all the more Christ’s solution to this impossible conundrum: that if all have sinned, that if all cannot avoid sinning—in judging, if nothing else—and if all must renounce judging, then the only way to judge not is to take on all those sins for one’s self. This ultra-radical acceptance of all sins by all people—not with resignation, nor with apathy, but with all love and hope, while still not condoning a single sin or transgression or act of selfishness or viciousness—is the only way to judge not, to genuinely have charity for all, to effect a radical reconciliation of everything and everyone, that is, to achieve At-One-ness, Atonement. In such moments, I begin to get an inkling of not only the scale but the sheer genius of the Atonement—while also realizing that this option is not open to me, because Christ has already accomplished it. In a way even Nietzsche couldn’t even comprehend, there really was only one Christian, and he died on the cross; I in turn, can only submit to his terms.

Not that any of these thoughts had occurred to me back on that sunny day in Palmas del Mar. At the conclusion of our brief visit, Manny Fox shook our hands politely, and Elder Rovira and I went on our merry way. Missions are littered with singular encounters like these, of which Manny Fox was but one of many. At the time, my only takeaway from the encounter was that rich people were just as crazy as everyone else. I left Palmas del Mar that day laughing, and was (or at least I hope) never intimidated by rich people again. No, there would be far greater things to be intimidated by later—because while at age 19 I assumed that “the last good Christian died on the cross” was just another standard parlay of atheist/agnostic snark, years later a part of me now wonders whether Manny Fox wasn’t sincerely asking that morning.